05 December,2016 07:53 AM IST | | Aditya Sinha

Indians love the idea of a ban, perhaps because of the deep belief that the only way to purification is through self-denial and pain

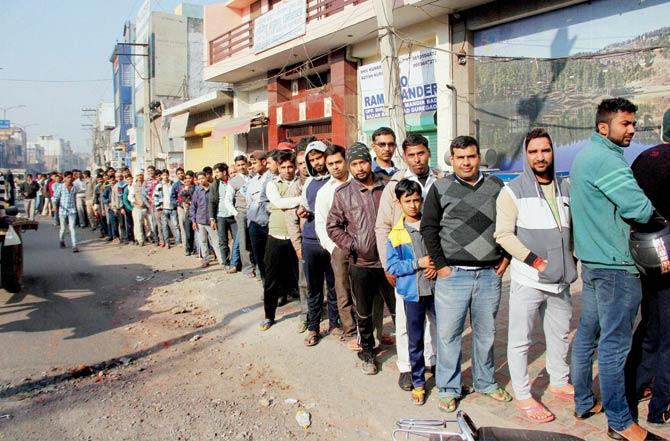

Our tradition makes every grand spiritual idea deeply embedded in even the most mundane daily ritual. Thus, the depressingly long bank queues are fairly orderly. Pic/PTI

Similarly, one of urban India's scariest phenomena is road-anarchy. In Chennai, I have seen a helmet-less motorcyclist suddenly halt in the middle of the road (not even at the kerb) to answer his mobile phone. In Delhi, people blithely ignore the side of the road they're supposed to drive on, much less do they heed lane-driving. Speeding is an apparently incurable addiction; Friday and Saturday nights are for radical experimentation. The Supreme Court or Modi might have all Indian roads torn up, or ban driving altogether. "All for the greater good," real estate developers, environmentalists and city planning academics might cheer. Not so much the people standing in the massive queues at bus stops and Metro stations: leave aside privileged society, the average young office-worker who has to share his/her already cramped space on the Metro with a deluge will curse. "BMKJ," he/she might mutter, without the slightest enthusiasm for the greater good.

Indians, it seems, love the idea of a ban or government regulation. No wonder prohibition keeps popping up in different states at different moments: its supporters argue for its social value (working-class husbands splurge hard-earned domestic savings) or its political value (Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar is trying to consolidate a constituency that transcends the usual caste alignments in his state). In the end, however, the government is just admitting defeat at the hands of market forces - and so bans the market entirely.

Even if we accept the government's tendency to over-mother us, what explains the citizenry's masochism? Admittedly, most readers are surrounded by middle-class sheep who repeat, ad nauseam, that the currency ban is for the âgreater good', and that it only costs 52 seconds of your time to stand for the national anthem. (It is only in rural India that you see people laugh at these abstractions that profit no one.) But even the bank queues look subdued (although one day a newspaper reported that there were 400 calls to Delhi Police's control room about ATM brawls) and the blockades on countryside roads are notable for how few there are. No one seems to wonder precisely what âgreater good' is being served, but they seem to think that it must be some good, at some point.

Perhaps this has to do with human faith in suffering and self-flagellation. Religious pilgrimage is all the more rewarding if there is a steep mountain to climb. The pious whip themselves into submission to God. I myself was on fast for several days during Chhath puja. Self-denial and pain is associated with cleansing and purification. Our tradition makes every grand spiritual idea deeply embedded in even the most mundane daily ritual. Thus, the depressingly long bank queues are fairly orderly. (Though there is also the possibility that Indians are on their best behaviour when it comes to transacting their money.)

Which makes me think that if the current suffering has a spiritual basis and not some concrete identifiable âgreater good', then what exactly is the patriotism that the Supreme Court is trying to stuff down our throats? It can't be the love of country, because there seem to be few Indians who have any love for their fellow countrymen (or country-women). That begs the question of what the country is: merely a piece of land? It couldn't be that, because you see people spitting and urinating and generally grabbing any square metre of motherland that they find. Ideologues have long said that it isn't the soil itself but the idea of the earth that they pay allegiance to. Thus the âgreater good' is just a polishing of that idea. And some thought there was going to be extra money in the bank (Rs 15 lakh per account, to be precise).

It's clear that nationalism is merely a substitute for mass onanism, like masturbation is a merely substitute for intimacy with a significant other. But enough of this namby-pamby analysis. Time to queue up to abuse our intellectuals, and stand up in honour of our neanderthals.

Senior journalist Aditya Sinha is a contributor to the recently published anthology House Spirit: Drinking in India. He tweets @autumnshade. Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com