The Baloch have more than one problem. They are just too few to matter in the calculus of Pakistan’s national politics, even though their province is 45 per cent of strategically vital territory. Despite being resource-rich, they are the poorest and most deprived in Pakistan

The Baloch have more than one problem. They are just too few to matter in the calculus of Pakistan’s national politics, even though their province is 45 per cent of strategically vital territory. Despite being resource-rich, they are the poorest and most deprived in Pakistan. Islamabad and Rawalpindi are interested only in the enormous natural resources that the Baloch possess but are not allowed to reap the benefits of this bounty.

The Baloch have more than one problem. They are just too few to matter in the calculus of Pakistan’s national politics, even though their province is 45 per cent of strategically vital territory. Despite being resource-rich, they are the poorest and most deprived in Pakistan. Islamabad and Rawalpindi are interested only in the enormous natural resources that the Baloch possess but are not allowed to reap the benefits of this bounty.

ADVERTISEMENT

Baloch have dreamt and steadily struggled for independence ever since August 1947, and have been suppressed brutally. Successive Pakistani regimes have kept the province subjugated, deprived and isolated, their voices stifled in an echo chamber. Foreigners, especially journalists, are persona non grata in Balochistan. Declan Walsh, then from The Guardian, was expelled for his ‘Pakistan’s Dirty War’ a graphic reminder of how gruesome the situation was in Balochistan. The Italian journalist Francesca Marino’s article ‘Apocalypse Pakistan’ would not have endeared her to the Pakistan authorities and she was refused entry.

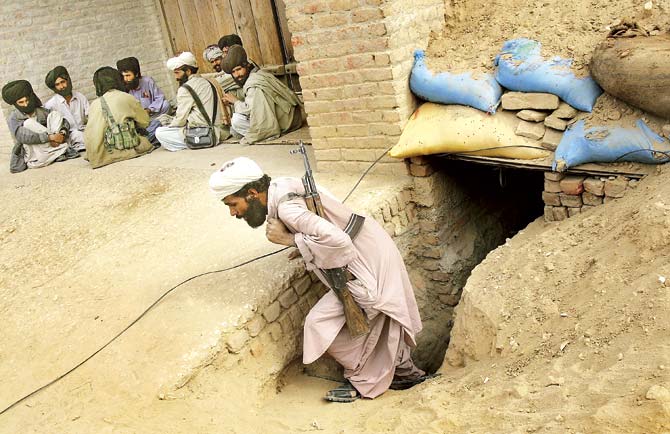

A Bugti guerrilla walking out of a bunker under construction in Dera Bugti, Balochistan. Successive Pakistani regimes have kept Balochistan subjugated, deprived and isolated. File Pic/Getty Images

More than that, several thousand Baloch men and women nationalists are known to have gone missing, and, as usual, the authorities have unleashed sectarian terrorists in Balochistan to discredit the nationalists by injecting their reliable hit men from the ASWJ, the successors to Lashkar-e-Jhangvi. They have repeatedly killed Hazara Shias in Balochistan.

The 2014 annual report of the New York-based Human Rights Watch refers to the crimes against humanity by the Pakistan Army in Balochistan since 1948. The report says that these acts include indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations, arbitrary arrests, extra-judicial abduction of Baloch activists and political prisoners, and targeted killing of most learned and educated members of Baloch society. Since 2010, authorities have pursued a policy of abduct, kill and dump. Enforced disappearances happen with impunity. Exactly a year ago, Zahid Baloch, chairperson of the Balochistan Student Organisation-Azad, was picked up by the Frontier Corps and his safety and whereabouts have remained unknown since then.

There was continued concern with encouragement to fundamentalists and groups like Ansar-ul-Islam, Al-Furqan, Lashkar-e-Islam and others to create cleavages between the Baloch and others who live in the province including Shias, Hindus, Sikhs and Zikris. A website www.crisisbalochistan.com reproduced an interview that Wendy Johnson had with Dr Allah Nazar, of the Baloch Liberation Front (BLF), in 2011. Dr Nazar referred to the battle in Dasht, Balochistan the BLF had with an ISIS front, Lashkar-e-Khurasan, that year and mentioned that the ISIS already had four camps in Balochistan.

There are other complications for the nationalists in Balochistan. The province is now on the high road of heroin smuggling from Afghanistan to Balochistan to the rest of the world. Heroin dons like Imam Bheel Bizenjo have been useful to the State by eliminating prominent Baloch activists. A BLF attempt to assassinate Bheel’s son, Yakub, in 2009 failed. But next year, they succeeded in killing Haji Lal Baksh, the second most powerful drug baron in Balochistan. Imam Bheel remains quite the Godfather under official protection, and when he murdered the Gwadar Deputy Commissioner Abdul Rehman Dashti in his house, not a soul stirred. Last year, in October, Baloch Sarmachars attacked and seized arms belonging to Imam Bheel. The nationalists are thus waging a multi-pronged battle against military forces, the air force, paramilitary forces, the political-criminal-military nexus and the religious extremist-intelligence agencies network.

There is also the China factor. Gwadar has been developed by the Chinese not as a luxury resort. It is part of a grand infrastructure project that links Kashgar in Xinjiang with Gwadar via the Karakoram Highway. The original road was to be west of the Indus running through Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa, but the Punjabi lobby prevailed and the proposed road will run through Punjab with obvious economic advantages. Both the Chinese and the Pakistanis are interested in keeping Balochistan under control.

The character of the Baloch revolt is changing. Mahvish Ahmed, in his detailed essay in The Caravan, New Delhi, brings this out. The traditional centres of opposition in the North East, led by Baloch Sardars like Marris and Bugtis most of whom have died, were eliminated or are in exile was now being replaced by a more urban middle-class leadership from the south.

Meanwhile, the Baloch carry on their campaign on the Internet and the social media, which may have some appeal outside but there is not enough global attention to their plight. Their struggle remains forlorn.

The writer is a former chief of Research and Analysis Wing (RAW)

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!