An upcoming exhibition of ancient and modern artefacts and works of art spanning over 5,000 years, celebrates age and the lines that come with it

Everything you see in this room here," says Anupam Sah, "is trying to return to the earth." We are surrounded by clay, metal and cloth objects — some at least a few millennia old. "Be it an electronic computer part or a piece of synthetic cloth —everything is trying to return to a stable, elemental form. And our job is to stop that," says Sah, Head of Art Conservation, Research and Training at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS).

ADVERTISEMENT

At the museum's conversation workshop, there is a strong recall of an operation theatre or a chemistry lab — there are conservators in white coats at each table and studio lights glaring down at them. Sah, who has been an art conservator for the last 25 years, splits his time across each section. He calls his job "an amalgam of science and art, tempered with informed human decisions".

As we sip our coffees on the corridor of the museum (food items are not allowed inside the workshop), Sah often evokes medical terminology — a diagnosis of an artwork is followed by an analysis and chemicals are tested for side-effects. But, whether they are scrubbing a Chola bronze with cotton buds or scanning an 18th century chintz prayer mat with infrared rays, the conservators' rule is only one: be invisible. "While conservation is about skills and knowledge, the conservator has to disappear into anonymity," says Sah.

Which is why the CSMVS' upcoming exhibition is an unusual one. For a change, the exhibition, curated by Sah, will have the conservator at the heart of the show; 50 objects, spanning a period of 5,000 years, will narrate more than just their stories and go on to explain how they stood the test of time. Will this exhibition demystify the practice of art conservation; perhaps reveal the trick a little too much? Sah will tell you that the exhibition is more than that.

"Art conservation is philosophical. Why did we choose to treat an object in a certain way? Why have we decided to leave the green patina on some bronzes, for example, or how did we conserve a Harappan storage jar?" Conserving the Collection: The caring path for 5,000 years of art opens on September 3 in the Premchand Roychand Gallery, CSMVS. Visitors will get to see these 50 iconic objects — almost 80 per cent of which haven't been exhibited till date — till November 1, 2016, and understand through them the nuances of art conservation.

Silk for the frail

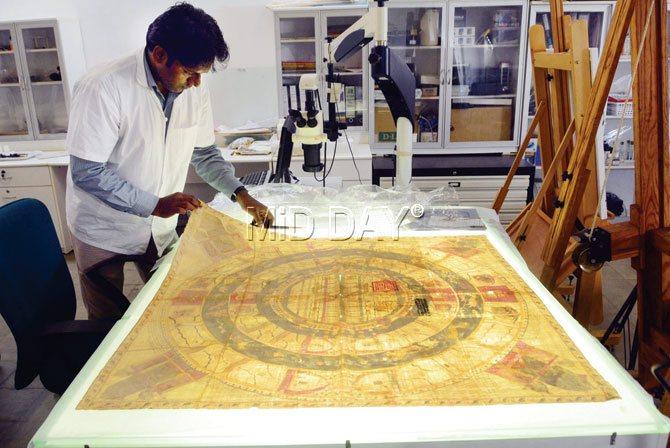

Nidhi Shah, projects coordinator, turns on an LCD backlighting table on which is placed a 1750 CE Jambudweepa, the Jain view of the world with Mount Meru at the centre of the island continent. Several bits have been eaten away by the ravages of time, and the holes speak for themselves.

"It is different if you are restoring a textile work for your home or to keep in the drawing room. But in a museum, the historical integrity of an object is important," says Shah, indicating a thin film of crepeline — almost invisible to the naked eye — that her colleague Prajakta Jadhav, textile conservator, uses to hold the painting together.

Laser surgery for the Buddha

In the middle of our conversation, Sah suddenly pauses and remarks, "Hear that sound?" From behind a translucent screen comes the steady sound of a pulse, and Sah takes us around. Conservators Dilip Mestry and Aishwarya Bhattacharjee are at work on a 5th century stucco Buddha from the Gandhara region. He has been cleaned up in patches with a fine laser beam.

"The instrument we use for this is the latest in art conservation. It is worth noting that while professions like fashion technology have advanced so much, art conservation is still lagging behind. And to think that museums have been around longer," says Sah. With every flash of the laser beam, centuries of dirt come away. Is it possible to turn back time entirely? "Yes, but we should allow the character of time to exist on these works. Remember that the laser beam is only an instrument; how we use it is more the point," he says. Done as patchwork, there is a clear before-and-after effect on the artefact.

Undoing old repairs

Conserving the Collection begins around 2500-1900 BCE — nearly 5,000 years ago — with a Harappan storage jar. It was used to store grain, but can easily accommodate a grown person as well. The jar is reconstructed from seven parts, but, first, conservator Nikhil Ramesh had to undo an earlier haphazard conservation.

Now, a new, finer filling holds the shards of the jar together, and the new repairs are easily distinguishable from the old to let history speak for itself. A gaping crack is left at the bottom of the jar. In a case of new-age technology meeting the ancient, this crack will be fitted with a 3D-printed piece.

Sah points to a little row of grooves around the centre of the pot. "In the making of such a huge jar, it is possible that the fresh clay would flop when it was shaped. There were strings that were wound around the pot in order for it to hold its shape, which remained once the pot was baked."

The funk in the edict

An Ashokan edict, unearthed in Nala Sopara and written in the Brahmi script, is one of the 14 major edicts in India. While it's a pity that it split into two during transportation from the site, it is now held together by an iron ring. If you thought that was conservation, there's more to it, explains conservator Rajesh Poojari, also an archaeologist.

"The edict was stored in the museum's repository and accumulated a lot of dirt and cement over the years. While most people think it is easy to wash a stone surface, it is difficult to do so when it has carvings on them," he says. As we shudder imagining how grime can settle into the carved words, 'Devanampriya Priyadarsin Rajah' during washing, Poojari says that a lot of attention has been paid to each letter using a special organic solvent.

Incompatible with the original

A far cry from the Harappan jar, the exhibition ends with a painting made in 1962 by one of Modernist VS Gaitonde. Sah says that a lot depends on the kind of materials chosen by the artist. "In the past, artists thought a lot about the paints and canvases they used. Works made then don't degrade as quickly as some works made by younger artists now," he says.

On this untitled Gaitonde work, conservator Omkar Kadu applies a filler to repair minor losses in the blue canvas. The filler's neutral tone neither stands out nor blends in. After all, you cannot paint over a masterpiece. And, the filler can simply be removed, since it is of a different nature than the original materials used in the painting.

Is it easier to restore a Gaitonde than a Harappan jar? Well, not really. "Two things", says Sah, "in Mumbai that are a problem for paintings are the weak quality of commercial mounting and framing materials and the low AC temperatures that people use in their homes. These can damage a painting irreversibly." Overall, while a Modernist masterpiece might need lesser intervention than a terracotta storage jar, Sah vouches that the conservator has no favourites.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!