From a tribe of former poachers in Ranthambore to another in Bandhavgarh that deifies the tiger, a look at communities that hope to save the striped one

A jeep of tourists encounter a Royal Bengal tiger at the Ranthambore National Park in Rajasthan.

![]() When we ask Hans Dalal about his childhood, he plays down the many battles. “I was born healthy, but contracted jaundice as a three-day old.

When we ask Hans Dalal about his childhood, he plays down the many battles. “I was born healthy, but contracted jaundice as a three-day old.

ADVERTISEMENT

That led to contamination of blood and damage to the brain although doctors tried blood transfusion on the fifth day of my life. I spent years going through occupational therapy, speech therapy and physiotherapy, until class 10.

Also read: Singer Sid Coutto talks about Hans Dalal's documentary

A jeep of tourists encounter a Royal Bengal tiger at the Ranthambore National Park in Rajasthan.

These days, there’s a limited effect (of the disability), but at times, I have balance issues and people think I’m drunk when I’m not. It’s good though, because I can get away with drinking and nobody can tell!”

After a successful run as sound engineer, he found his love for the wild. “My uncle, aware of this, took me for a camping trip to Kanha in 2007. It was a short tiger sighting, but something changed. I spent the next year researching the reasons for

the decrease in the number of tigers. I’ve been obsessed ever since,” shares Dalal.

Cause of the tiger

In March 2010, with support from an NGO called Tiger Watch, Ranthambore, and a few friends, Dalal, along with musician Sidd Coutto, recorded music with ex-poachers, from a tribe based in Ranthambore, with the intent to produce and sell their music and ensure alternate sources of income to kick off a rehabilitation programme.

The team spot a tiger in Ranthambore

The team spot a tiger in Ranthambore

“I was introduced to the Moghiya tribe through my uncle, Fateh Singh Rathore, the legendary tiger expert and conservationist. It was obvious that they needed an alternate source of income. I heard their music, and realised that they needed a voice. Therefore, I decided to record them for the documentary and use my sound engineering expertise.

It took a year of planning and getting musicians on board. My friend, Sidd Coutto came along to Ranthambore to help,” adds Dalal.

“They are untrained musicians and very shy. Police and forest guards are after them, so they have become reclusive. It took a while for them to trust us. I made 19 trips to Ranthambore in a year.

Moghiya tribals

Coaxing them to record was difficult. We had trouble with space too, as our makeshift studio was too small and reverberated with the sound.

We improvised by putting mics on the bonnet of our jeep and recording in the open. I remember a tribal who was unable to sing without playing his sarangi and unable to play the instrument without singing.

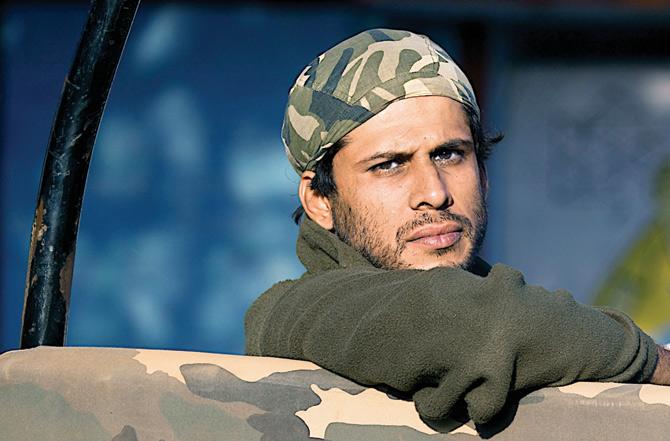

Hans Dalal

Recording that was so difficult because of the sound bleeding between the voice and instrument mics,” he recalls.

Ground reality

The team spent a year-and-half on the documentary of which four days were spent on the actual shoot. With help from TigerWatch, the tribes have now been trained in making handicrafts, repairing cars and bikes, and working in hotels.

“Very few people know about the tribe. People have a prejudice against poachers but tribal folk had no alternative. They have lived in the jungle for over 300 years. When the area was converted into a tiger reserve, the government gave them land but they didn’t know how to farm.

They are very good at what they do. They can kill a tiger in a jiffy,” says Dalal. “The British labelled them a criminal tribe. It has been difficult for them in a place like Rajasthan, where the caste system has a hold,” he adds.

![]()

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!