Ahead of Mahesh Dattani turning his book, My name is Gauhar Jaan: The Life and Times of a Musician into a play, Vikram Sampath discusses his muse

Q. How did you first come across material on Gauhar Jaan?

A. While researching for my first book, Splendours of Royal Mysore: The Untold Story of the Wodeyars, on the history of the royal family of Mysore, I came across the name Gauhar Jaan in the palace archives. Though she lived in Kolkata for a large part of her life, she spent the last two years in Mysore and died there on January 17, 1930. Letters and correspondences between her and the Government of Mysore were fascinating; she pleaded for money and assistance in legal battles that were hounding her.

ADVERTISEMENT

Also read: A hundred years of unsung love

Gauhar Jaan in a recording studio

Q. What about her made you write the book?

A. The fact that Gauhar was the first Indian to record on the gramophone drew me to her life. The gramophone company's advertising material described her as the ‘first dancing girl of India’. The few snippets that I gathered about her seemed to indicate a stormy life. For someone who was a celebrity in her heyday, the fact that she had resettled from Kolkata to Mysore, and that too, on a measly pension, seemed to indicate that she had gone through a lot. She was perhaps frustrated and exhausted by then. I was seized by some strange and inexplicable obsession to unearth more about her life

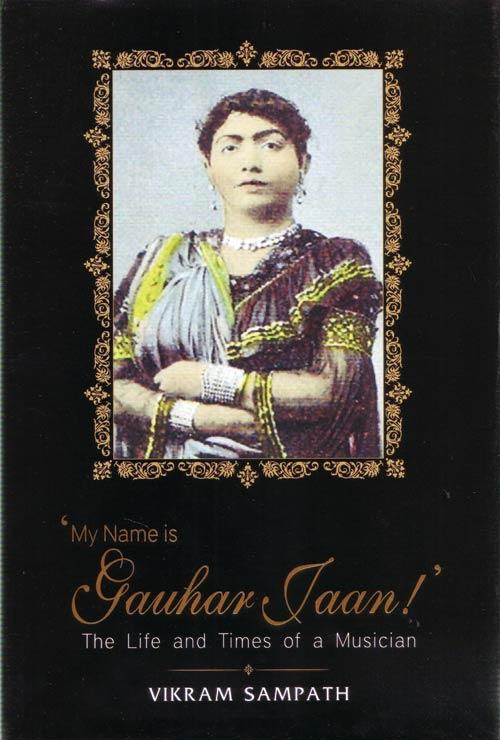

The cover of the book My name is Gauhar Jaan: The Life and Times of a Musician. Gauhar Jaan’s pictures also appeared on postcards and matchboxes manufactured in Austria

Q. Was material on her easily available?

A. Documenting the arts in India is perhaps one of the biggest challenges for a researcher. There are undoubtedly several musical treatises that have survived since ancient times. But we know so little about the nature and content of early performances, and more importantly, about the lives of yesteryear musicians, that their personal lives and challenges they faced have been completely lost. Music, therefore, seldom has a history and survives largely through anecdotal memory. It was no different in the case of Gauhar Jaan. Someone who was a celebrity and a rage across the country, whose pictures appeared on postcards and matchboxes manufactured in Austria, who was India’s first voice to be etched on the shellac disc, is today almost forgotten and unacknowledged, even by Hindustani musicians.

Q. Tell us about the process of collecting this information.

A. The overall research for the book took nearly six years. I have tried to back the general template of her life with supportive documents that were very tough to procure. Along with that, I found Urdu poetry by her mother, Badi Malka Jaan, who had published her book of ghazals, ‘Makhzan-e-ulfat-e-mallika’ in 1886, as also excerpts of diaries and writings of Frederick William Gaisberg, the German agent of the gramophone company who recorded her. The book comes with a CD of some of Gauhar’s original tracks digitised from original 78 RPMs.

Q. How did the play come about?

A. Mahesh Dattani is a long time friend. In fact, we were discussing the idea of the play even before the book came out. He said Gauhar is a subject waiting to be feted on stage and celluloid. So things worked out well with Lillete Dubey and the Prime Time Theatre (the producers of the play), who showed a keen interest in the project. My Name is Gauhar Jaan: The Life and Times of a Musician, Vikram Sampath, Rupa & Co. Rs 539 available at all leading bookstores.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!