Filmmaker Shivendra Singh Dungarpur recently discovered the reel of the first Konkani film, Mogacho Aunddo (1950). He tells Kareena Gianani about the rare discovery, the painstaking process of restoration and why we must care about it all

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur

Filmmaker Shivendra Singh Dungarpur says he is a man who is always waiting. He wonders who will walk in through his doors next, with an old, decaying film reel in their hands. “Celluloid film is being discarded on the scrap heap every day. I am constantly looking for films to save. Every second day, I have kabadiwalas walking in with old reels mostly in dilapidated old cans, sometimes wrapped in a newspaper — imagine my dismay! Then, I take the sometimes hardened (mostly acetate) films to my turntable to soften them; it is like watching the birth of a child,” says the director who made Celluloid Man (2012), and founded the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) in January 2014.

ADVERTISEMENT

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur is restoring the print of the first Konkani film

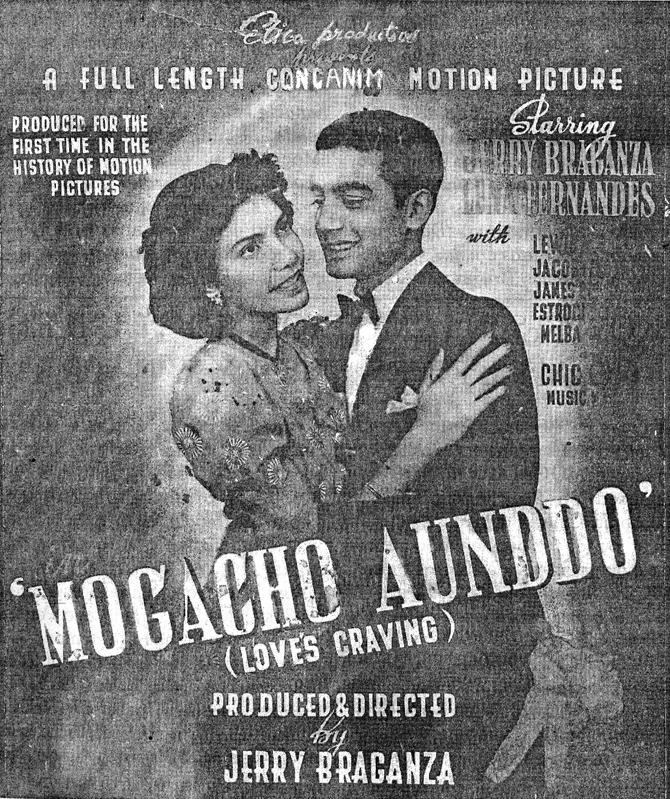

Last week, it was National Award-winning filmmaker Bardroy Barretto who met Dungarpur and gave him the reel of the first Konkani film, Mogacho Aunddo (Love’s Craving), made in 1950. The film, produced and directed by Jerry Braganza is a love story between a rich boy and a poor girl.

Dungarpur was stunned, but his awe soon changed to shock when he saw how hardened the reel had become over decades. “I have sent the reel to L’Immagine Ritrovata, a laboratory in Bologna, which does world-class, full-fledged film restoration,” says Dungarpur, and adds that he is waiting to hear how much of the reel can be restored to its former glory, if at all. “Restoring this film can tell us so much about Konkani cinema and Konkani society. But film restoration is expensive and we will need to raise funds if we are to save this film,” says Dungarpur.

Mogacho Aunddo

Barretto chanced upon the reel while he was researching for his film, Nachom-ia Kumpasar (2014), a tribute to the unsung musicians of Goa, and met former banker, Isidore Dantas. Dantas is an avid collector of Konkani film memorabilia and had been ardently scouring for all the original reels of Mogacho Aunddo since a few years.

Stills from the films Khazanchi and Kismet

“He had approached other collectors to see whether they could help him restore the reel, but failed. Dantas finally handed it to me, and I to Dungarpur,” says Barreto. “Meanwhile, Dantas is positive that he will find the remaining reels of Mogacho Aunddo somewhere in Africa (like Goa, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Príncipe and Equatorial Guinea, too were Portuguese colonies) or in Macau (an erstwhile Portuguese colony),” smiles Barretto.

It isn’t difficult to gauge that Dungarpur is a filmmaker who goes beyond the ‘now’ of filmmaking — his ethos towards the history of cinema is palpable in his words and work. “I have always felt deeply towards the art of preservation, but it was after reading Martin Scorsese’s interview about Bologna in 2010 that I decided to visit the place, and that sparked the idea for the foundation. When I collaborated with Scorsese and his non-profit organisation, The Film Foundation and World Cinema Foundation, to restore Uday Shankar’s film, Kalpana (1948), I wondered why we didn’t do this first!” exclaims Dungarpur.

The filmmaker set up the FHF last year to preserve India’s cinematic heritage in all languages. He also emphasises that without interdisciplinary educational programmes, efforts at preservation are incomplete. In February, Dungarpur collaborated with Scorsese’s foundation and launched the week-long Film Preservation and Restoration School to applicants from India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan.

Film preservation in India, feels Dungarpur, owes a great deal to the shops of Chor Bazaar and collectors like the late Abdul Ali of Cine Society, who trawl through the streets to find rare material. As we go digital, he adds, labs are shutting down and film cans are discarded by the thousands. “Producers, copyright-holders and people at large believe that celluloid is obsolete and that digitisation is the same as preservation. But how is that restoration when it does not repair the original source material?” he wonders.

Dungarpur wants to ensure that the students of the FHF school find lucrative career options in the field of restoration and preservation. “India has only one film archive — the National Film Archive of India, but that’s not enough. It has limited funding and is short-staffed. It is too much to expect the NFAI to shoulder the responsibility of preserving our cinematic heritage alone given the sheer volume of films that India produces,” he opines. “The main reason for the colossal loss of our film heritage is our attitude towards cinema. It is not just an industry for mass entertainment; the moving image is an art form and an integral part of our social and cultural heritage,” adds Dungarpur.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!