Prerna Singh Bindra’s new book, When I Met the Mama Bear, is a hat tip to India’s forest guards, who are silent protectors of our forests and national parks. Excerpts from an interview with the naturalist-author

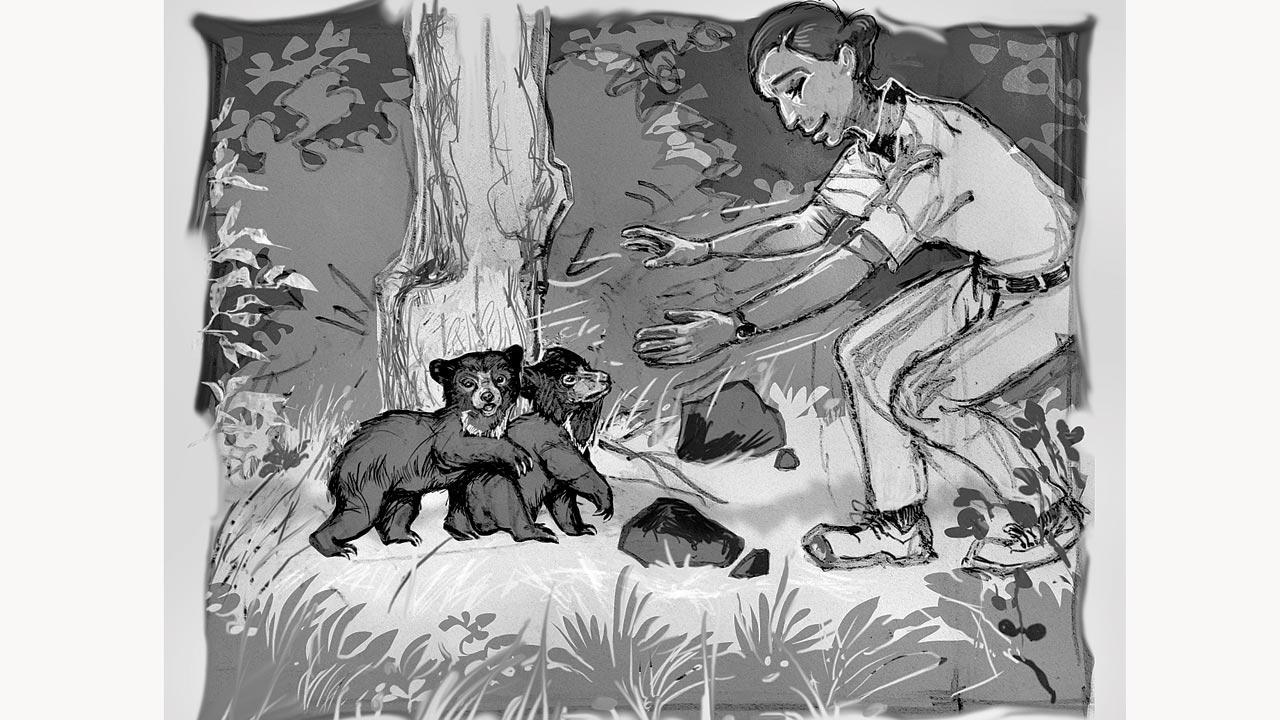

The book salutes India’s forest guards and their relationship with fauna. Illustrations/Maya Ramaswamy, Talking Cub, Imprint of Speaking Tiger

You have paid rich tribute to India’s forest guards and staff. Tell us when did you first encounter and learn more about their inspiring lives.

I cannot pinpoint any ‘first’ encounter — there have been many memorable, humbling meetings. I remember a number of these unsung green heroes, climate warriors, whom I have met, interacted with and learnt from my forays into the wilderness over the years. How many can I tell you about: the fire watcher who spends scorching summers perched on a flimsy platform some 50 feet above the ground, on a tree in Kanha Tiger Reserve to keep vigil and alert park authorities in the event of a fire; the fiercely courageous Van shramik in Sundarbans who found himself trapped in a cage with a tigress in the chaos of a rescue operation (he lived to tell the tale!), the dedicated forest guard in Corbett who wouldn’t go on leave — even to see his family — as his turf would stay unprotected, the grieving family of a forest ranger in Chhattisgarh, who was killed by the stone mafia as he tried to protect a forest and river even in the face of death threats, the utterly inspiring ranger who has walked the forests of Dachigam (Kashmir) since the age of nine — and has risked, and devoted, his life to the park.

ADVERTISEMENT

The germ of the idea occurred in Melghat. Did this book take shape then, or did it come to life over consecutive visits to

the place?

I have been visiting Melghat since 2003, though nowhere as often as I would like to! As I mentioned in the book (Talking Cub), this story of the Mama Bear was narrated to me by one of Melghat Tiger Reserve’s forest guards. She was very moved by this mother bear incident; and once she knew I was a writer-conservationist, she was excited, and wanted me to narrate it to the world. I promised her I would. I have constantly been in touch with her, ensuring she was on board with everything that was narrated. I must add here that there has been some dramatisation of the story. The book took its time; life takes over even as you plan. I am more nervous than usual this time when my book stepped into the world, I was wondering if I have done justice to the protagonists of the story.

Prerna Singh Bindra

Prerna Singh Bindra

By humanising characters in their natural setting, you’ve introduced readers to these silent green warriors. What message do you hope this book can give to India’s urbanised, national park-visiting tourists?

Many visitors who sign up for safaris usually return to see the animals, and are unaware of what it takes to protect wildlife — the great risk forest staff and others who work to conserve wildlife put themselves in, the complexities that are involved, the pressures they face. They are usually captivated by the wildlife — how can one not — but what does it take to keep the wildlife alive?

We must recognise these frontline women and men to whom we owe our wildlife, our forests and the rivers that flow through them. To value them, we must value our ecosystems — forests, grasslands, wetlands, rivers and oceans — to whom we owe the water we drink, the food we eat, the air we breathe. Our natural ecosystems are the basis of life. And if we are to protect these, we must recognise, respect, motive, equip,

enable and empower our Green Army.

This book takes the reader on an organic joyride, while raising key issues about conservation and wildlife. Was that always part of the storyline?

Thank you. It gives me the satisfaction that I have ‘achieved’ in part what I set out to do when I write — engage the reader, draw them in into the story, inspire them to care. There was no plan; in some ways, the message is the story itself — that animals are not automatons. They have feelings, agency, they are social beings with their own kinships and sensibilities to navigate their world. I wanted to expand our limited perception of animals [apart from humans], and lure people into their mysterious, magical world. So, in my writing I try to weave in the nature of animals — to break the prejudices and misconceptions that surround them.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!