Here’s our report card after we took a peek at the unexplored and unseen parts of the museum at CSMT as part of a re-launched heritage walk

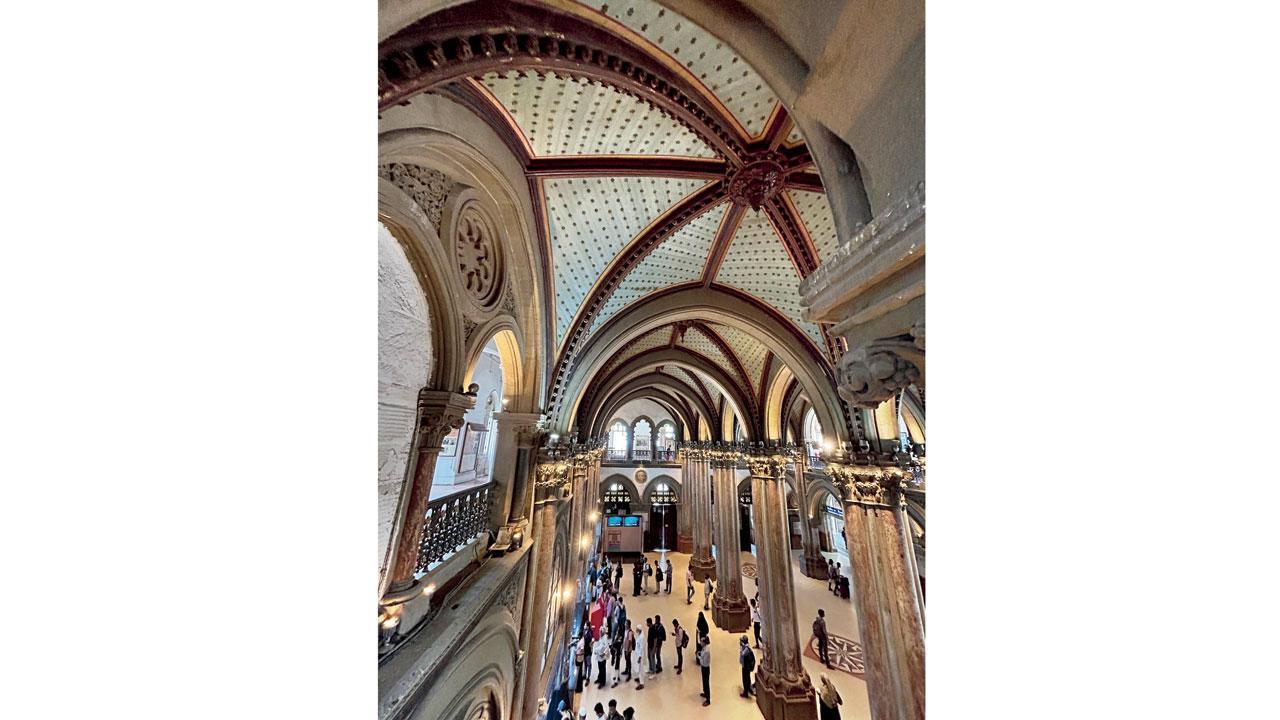

The ticket counter at the station is called the star chamber, owing to its star-filled ceiling

The meeting point for our heritage walk inside Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (CSMT) on a Saturday morning is outside the McDonald’s outlet facing the mighty railway terminus. When we reach the destination, we spot two older women, accompanied by a girl in a sky-blue T-shirt that reads Raconteur. We approach the trio who will be our companions for the next hour and a half that rewinds into the rich past of the former Victoria Terminus, known as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus since 1996. Anushka, sporting the blue tee, is our guide for the day as she leads the group of three into the Gothic structure which also houses a museum.

ADVERTISEMENT

The CSMT tower clock is a mechanical clock and is keyed 14 times on Thursdays and Tuesdays every week between 10.25 am and 10.30 am. The statue atop the dome is called the Statue of Progress. It is often mistaken to be a statue of Queen Victoria, after whom the terminus was originally named. Incidentally, Queen Victoria’s statue, placed right below the tower clock, went missing rather mysteriously after in 1950. The space below the tower clock still remains vacant.

Outside, on either side of the pathway leading to the museum, a few original objects from railway stations of the early 20th century are displayed. These include lamp posts, a massive metal money-storing box for the ticket officer, an old hand lever (to manually change tracks) and railings among other objects. Despite our guide’s briefing on the functions of these shiny, restored artefacts, we were keen for more details. Hence, we scan the QR codes placed beside the displays to access additional information. We were expecting a page specially created by the museum’s team filled with rare facts about that particular historical object typically unavailable on search engine platforms. Instead, it opens up a Google search page suggesting random, and sometimes unrelated, articles.

A polished and original old hand lever from 1887. It was used to change tracks manually

A polished and original old hand lever from 1887. It was used to change tracks manually

Next, we are introduced to a model of an engine of the first train that ran from Bori Bunder — which our guide says is somewhere where today’s Haj Centre is located — beside CSMT. She explains how this day was declared a holiday across the city, as people gathered near the tracks to witness the one-hour-long journey to Thane, which would’ve previously taken weeks or even months.

The silver cutlery from the first class compartments that were reserved for the British

The silver cutlery from the first class compartments that were reserved for the British

“We have travelled in these kinds of trains,” shares one of our senior companions, Hafiza, sensing that the writer had never seen a steam locomotive in their lifetime, “By the end of the journey, our faces would turn black, and our eyes red, because of the coal. Every compartment would have at least one severe case. And yet, people would fight for a window seat.”

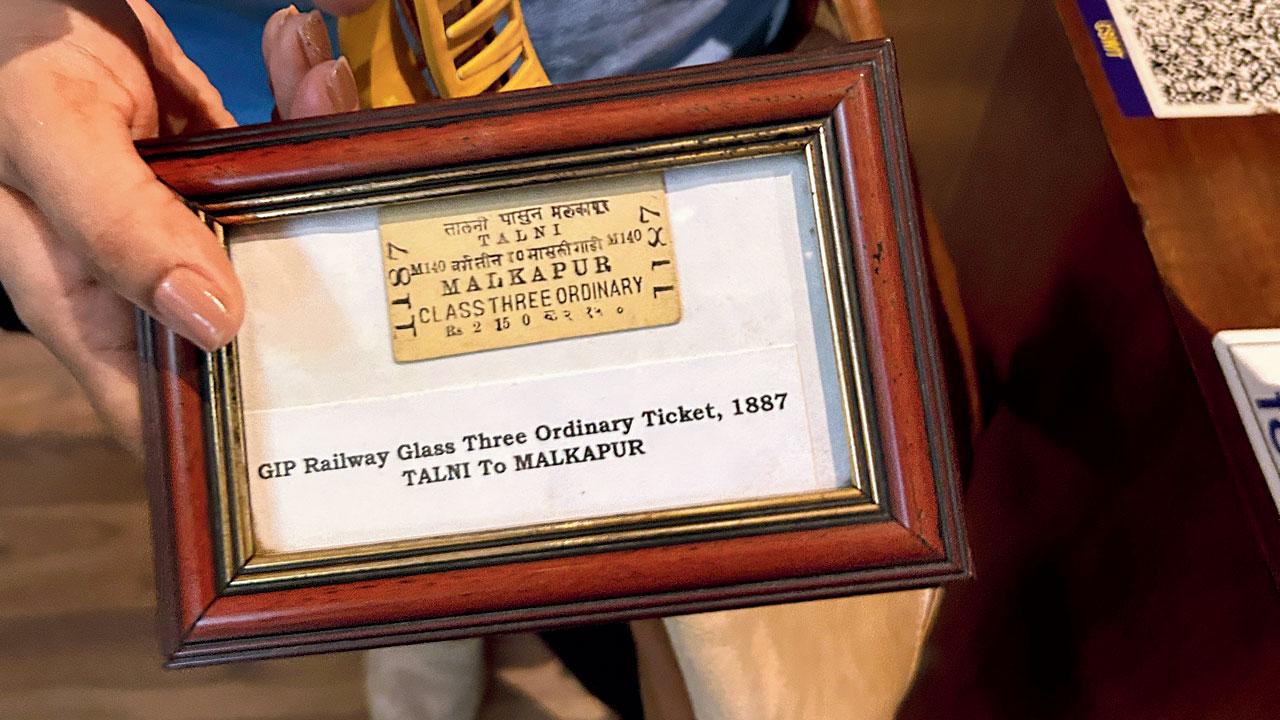

An 1887 ticket from Talni to Malkapur

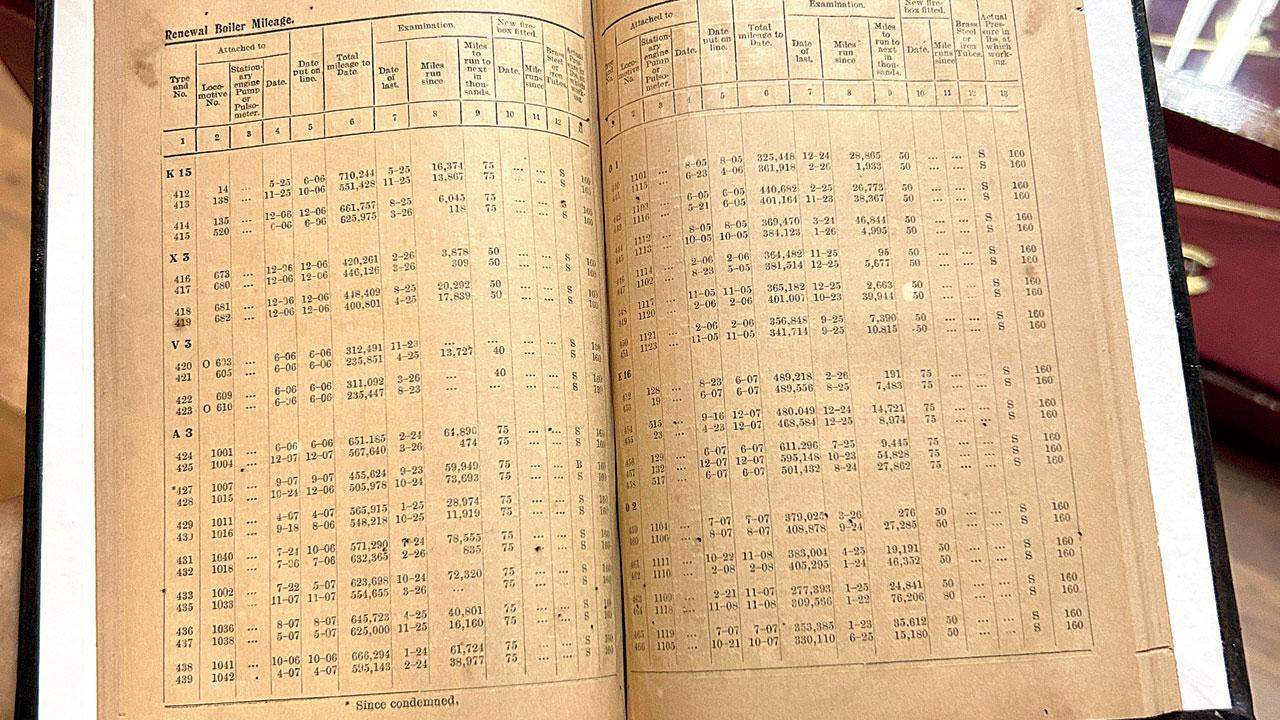

Following an elaborate account of history that highlighted why the building was conceived, details about its architect FW Stevens and how it took a decade to execute the construction plan, we observe the evolution of railways across the city and the Subcontinent via maps, representative images and models; the anecdotes narrated by our guide and some of our companions add value to our time. Other preserved originals include a book recording engine and boiler mileages from 1926, an 1887 ordinary class ticket from Talni to Malkapur both located in today’s Maharashtra, a GIPI signal, ticket punching machine, mechanical clocks, and silver cutlery for first-class commuters — all British citizens. The displays are well maintained and in operational condition.

A record book from 1926 by the Great Indian Peninsula Railway for train engines and mileage. Pics/Devanshi Doshi

We observe the architecture that includes intricate carvings on the outer façade, before re-entering the building. But our guide keeps the next halt a secret. As we pass through another gate, we are requested to not look up until we are standing in the middle of a hall. She counts down to three and we look up together. We are mesmerised by the dome, which is decorated by eight stained-glass windows that are comprised of 16 glass partitions in total; there are eight galleries and eight openings to the floors. The cantilevered staircase that runs along the walls is the only distinguishing feature that divides the octagonal structure of the building into four distinct angles. “The only function of the dome is grandeur,” she says, breaking the spell.

Our final halt is the balcony on the second floor that faces the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) building. From there, we spot passers-by rush into the station. Some pause for a selfie. No one looks at us. “We were down there a while ago. We didn’t look up either. This is testament to the city’s fast life,” nods Hafiza. Throughout the walk, our guide took questions and shared relevant answers by breaking down the historical events chronologically without jargon. The experience was enriched by the anecdotes and reminiscences shared by our co-participants.

1888

The year in which the construction was completed

Duration of walk: 90 minutes

Log on to: in.bookmyshow.com

Cost: Rs 500

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!