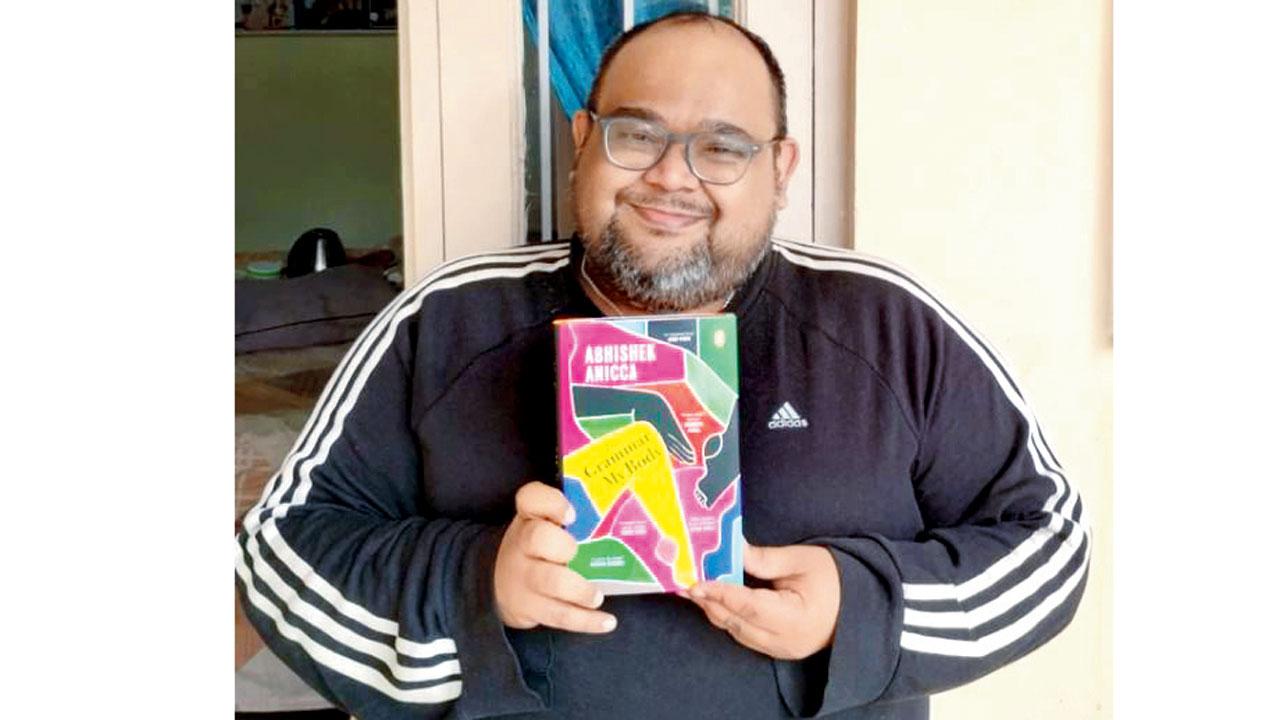

Writer-poet Abhishek Anicca speaks about living his truth unapologetically and revolutionising self-love to dismantle ableist normative structures in his upcoming book

The writer emphasises on practising poetry as an act of self-love and calls it a hopeful thing. Representation Pic

Throughout Abhishek Anicca’s The Grammar of My Body: A Memoir (Penguin Random House) the writer, poet and spoken word artiste approaches his experiences with fierce honesty. This journey travels through a series of 41 essays written over the last five years about coming to terms with locomotor disability and chronic illness in a society that embodies ableism. The book’s release this month coincides with the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1992 and observed annually on December 3.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dismantling the narrative

Through the essays, you encounter Anicca’s truth as a direct challenge to and rejection of inspirational narratives, the ableist expectation to ‘overcome’ disability; an approach that disregards the struggles of persons with disability, in order to make disabled experiences palatable and normative while sidestepping the responsibility of taking down an exclusive societal structure.

In his book, Anicca points out that the society should be more empathetic and realise the importance of interdependence over independence. Representation Pic

Honesty is his weapon

Anicca does this by asserting his truth and breaking through the tough stance of self-love in a world that wants persons with disability to embody shame. In chapter five, he writes: “I have become an expert of draping my stories before they become too ugly... it is time to slowly undrape it”. In writing about navigating an exclusive infrastructure, sex, shame, dating, diapers, and facing ableism, Anicca, 36, speaks with vulnerability, and in doing so, asserts power over these inspirational narratives. This makes the book an important read for able-bodied people.

Living one’s truth

As the book progresses, Anicca turns this honesty inward to reckon with the impact of living in normative structures as a person with disability. Here, he speaks for the sake of self, and not from the projection of the ableist gaze. Over a call from Patna, he shares, “Bodily expectations are societal, and we embody all our experiences.” Living with a physical disability pushes one outside these normative expectations. He continues, “So I have to approach my experiences with a realness. Then I will begin to see the person I am within. This is where you realise that these normative truths are not universal.”

Pic Courtesy/Twitter

He continues, “There are two approaches to being vulnerable. Either you hide your vulnerability or you talk about it. Me speaking about aspects of my disability is not an exercise in truth-telling, it is me living my truth. And this can be very challenging because it shapes the perception of yourself; it’s more palatable for everyone to hide a vulnerable truth. But what is the point of hiding?”

In the essay A Nonchalant Conversation about Death, Anicca poses the question he often asks himself, he writes: “Have you lived your truth? Yes. Yes. An empathetic YES.” He shares the weight this question carries and how it rejects the ableist gaze, explaining, “Truth is liberation and self-preservation. It is also preparedness [when subjected to ableism] so that it doesn’t destroy you. Yes, it opens you to vulnerability which can take the form of self-love or self-loathing, but you have to choose the truth that helps you survive. I have no choice but to live my truth. I don’t want to build a fog around myself. I want to look at myself and my body in the mirror.”

Hope through radical self-love

Many of his personal essays are marked with undertones of hopefulness that are ushered by revolutionary self-love, existing outside of the ableist-catering performative narrative. There is also a cyclical pattern of losing and reclaiming hope in living with a chronic illness that Anicca documents. Perhaps a stark acknowledgment of this cycle lies in the essay.

Some Long-lost Poems, where he writes: “I die every day as a poet, I survive by being an accountant”. A pragmatic approach to hope. “If I’m not hopeful while recovering, what will I be?” He says, “I want to be hopeful when I end an essay not for anyone else but as a practice.” He continues, “Writing a poem is a hopeful thing because when you write about losing hope, you gain some. There is so much humanity in a poem.”

Through prose that is poetic, Anicca builds a radical narrative about which he says, “In personal storytelling, the narrative has no end goal or arc when you are living it. Here the story’s poetic effect — whether beautiful or ugly — lies in truth. And that carries weight. My story is not about survival because that would feed into the inspirational narrative, it’s about my experiences, truth, and finding that clarity through a pen.”

Our favourite learnings: Lines from Anicca’s book

>> What is self-love? Isn’t accepting your disabled and ill body a form of self-love?... If eating chocolates and a tub of ice-cream is a form of self-love, then boss, I have been there too.

>> If only as a society, we would have been more empathetic and realised the importance of interdependence rather than independence.

>> It’s not just our responsibility to adapt to a situation. Everyone around us must adapt too. Only then will we be able to live a life of dignity and respect.

>> Unspoken empathy is golden. Its worth keeps rising in my book. Not rare, but there’s plenty of cheap stuff pretending to be gold.

>> My spine disappeared one day and I started speaking with guile and you called me normal.

>> Loving yourself is an exercise that doesn’t involve any exercise. Although it does require a revolution or two.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!