While Mumbai awaits a report on the grandiose plan to revive its port lands, a tour of its bunders reveals a story of illegal trade and damage to ecology

There are no signs of clouds, but with an umbrella tucked into his coat, Mohan Mayekar walks out of a run-down Mumbai Port Trust (MbPT) office at Lakri Bunder to stride towards the wharves. As he nears the waters, an overpowering whiff of tar and wet ropes hits him. He tilts his chin up slightly to take in the view — the piece-by-piece breaking of end-of-life ships that sit like corpses in this graveyard, which is one of many along Mumbai’s 28 km-long eastern docklands that stretch from Colaba in the south to Wadala in the north.

ADVERTISEMENT

For the last 30 years, the 58-year-old MbPT employee has supervised all commercial activity, largely surrounding timber trade, at Lakri Bunder, one of eight bunders, or piers, that dot the coastal city’s now derelict eastern docklands. The frenzy of commercial activity that he remembers from decades ago is only a memory. The port that helped catapult Mumbai into a trading station in the 19th century is now abandoned, and inaccessible to public. “They (bunders) are no more than ghosts of this city’s industrial past,” Mayekar sighs.

What about flamingoes? At the Sewri jetty, ship-breaking activity is said to have been limited to protect the flamingoes that arrive here every year on account of the mudflats. But it’s clear that rules aren’t being followed

“While Mumbai has changed character and colour, time has stood still for the wharves.”

The construction of the JNPT port at Nhava Seva in the 1980s whittled down traffic on this side to half. Years of neglect has meant the gradual death of the once swarming bunders. Their decline is testimony to the city’s inability keep pace with its changing character unlike Rotterdam, Cardiff and London that recognised the need to modernise their ports and release excess port land to meet deficiencies.

Graveyard of ships: On the south side of Lakri Bunder, a wharf divided into 12 vacant plots, ship breaking carries on in full swing. The MbPT rents out land to ship breakers for a defined occupancy rate. While the breaking activity may be marginal, its environmental impact is manifold. The labourers work in the absence of protective gear, exposing themselves to toxic substances. Pics/sharad vyas

In fact, it is now well known that former prime minister Indira Gandhi released a directive in August 1980 that the construction of JNPT would lead to the release of land and dock areas at the existing Mumbai port for parks and public amenities, and work towards decongesting what was then Bombay. The Mumbai Docklands Regeneration Forum was quoted in the media, saying that that between 1988 and 2008, the MbPT had defied the directive.

Slums at a height: At some bunders, slums have come up on stilts several meters into the sea. The homes lack sanitation, and release most of their daily waste directly into the sea.

But Mumbaikars aren’t the only losers with an opportunity squandered. Rampant and illegal berthing of vessels and barges is causing losses amounting to crores to the MbPT itself. According to its own data, there has been an overall increase in the port’s net deficit from Rs 87.42 cr in 2012 to Rs 360.7 cr in 2014.

“Since both, liquid cargo, including vessel operations and stream discharge of cargo, and estate income are profitable, it can be concluded that the losses are on account of two main factors: dock and bunder operations,” says RN Sheikh, senior port manager and former in-charge of the Docks Department.

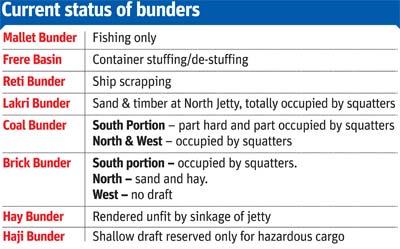

Nearly 79 vacant plots make up the eight bunders that cover an area of 30.6 hectares. The principal activities carried out here vary from unloading coal for regional power plants to raw fertilizer and liquid bulk unloading at Hay Bunder; ship breaking at Lakri Bunder and Powder Works Bunder. Tank Bunder has been used for parking small crafts. Haji Bunder is earmarked for storing International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) class containers that are to be handled at Offshore Container Terminal (OCT) berths.

Official neglect apart, some piers, including Hay, Haji, Lakri, Reti, Brick, Mallet, Zakeria, and Frere, suffer from the curse of nature.

They depend largely on a tidal window to help maneuver barges that bring in goods from the mother vessel.

The tidal window provides a draft (depth of sea) of 4m to 4.5m. Although contemporary shipping requires a draft of more than 16m, Mumbai has a maximum draft depth of 10.5m around the bunders.

A recent internal MbPT report, in possession of this newspaper, puts the blame squarely on excessive commercial silting around the bunders by port authorities. “We have not been able to crry out a transformation like at Rotterdam Port, Netherlands, which was shifted from its present location on the river Maas within the city further out at sea to acquire a draught depth of more than 23m. This raises questions about the future growth potential of the port at its present location,” the report reads.

What this reporter found during a walking tour of some of these bunders:

Zakeria Bunder

On the Western side of working-class neighbourhood, Sewri, sits Zakeria Bunder, which hosts a mix of residential and industrial units. A large portion of open land has been encroached by informal and illegal settlements that are identified by its residents as Chatai Chawl and Kranti Nagar. The lease structure here is fluid and usually stretches over 15 months. But, most leases breach rules, whether with regard to construction of permanent structures or change of user, notes an internal report of the port’s Estate Department, dated November 2014. Nearly 178 cotton depots and godowns that stand here are in dilapidated condition, threatening to collapse if not pulled down urgently.

Hay and Haji Bunder

Hay Bunder is sparingly used for barge traffic that approaches the shore when the tides rises, and allows cargo to be unloaded. Reports concerning the Docks Department point out that this bunder has been carrying out ship breaking for scrap recycling, and bunkering activities in a manner that’s hazardous to the environment, staffers and marine ecology. The release of toxic substances including asbestos and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) is one reason why ship demolition is no longer carried out in developed countries.

Defunct godowns: At Hay Bunder stand a row of dilapidated warehouses that were once used to store goods that came in from the Gulf.

Two port premises leased out to corporate giants Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) and Tata Mills have been lying unused for years, with port authorities trying unsuccessfully to evict them. “HUL was leased 10.4 ha of land, one at Mazagaon Sewri Reclamation and another at MSR Road, for purpose of company’s branch office. But the offices have been shut, and the premise is vacant. The port has now moved the government to terminate the 30-year-old lease,” said a senior port official.

Black mountains: At Haji Bunder, coal needed by regional power companies is stored. Due to oversilting, this pier suffers a very shallow draft depth

At Haji Bunder, mountains of coal pile up, speaking of the damage they are causing to marine ecology and the mangroves. The Maharashtra Pollution Control Board has in the past raised a red flag about the deposits. Unions, however, contest the claim. “The workers are employing all necessary precautions. It is the Union Ministry of Shipping and certain vested interests that are after this land,” says RM Murthy, PRO, Transport and Dock Workers Union.

Brick, Cola, Lakri, Tank Bunders

With the outdated 19th century open-finger profile of these four bunders, they have turned into fertile ground for ship-breaking activities, often carried out using outdated technology. But before the ship is dismantled, it is dragged to land in medieval fashion through heavily silted water. “The hauling of vessels with the help of a winch is not only dangerous to the bed of the shore, it can also leads to accidents. But we have little or no choice,” says Shreenath Seth, a leading ship-breaker and merchant who operates at the Mumbai dock.

Sand mafia at work: Reti Bunder has turned into a den of illegal sand mining activity. The sand heap you see has been brought in from Konkan and dumped illegally at the bunder. This red sand variety is usually used for interior decoration purpose.

Thick encroachment is an added threat with slums having come up on stilts several meters into the sea. It’s a sight you are unlikely to witness anywhere else in Mumbai. The homes lack sanitation, and release most of their daily waste directly into the sea. A recent notice sent by MbPT to the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), reads: “While these slums lack basic infrastructure like drainage and water supply, the problem is compounded with the BMC directly discharging sewerage at Lakri Bunder Basin without any treatment.”

Mallet Bunder

An existing jetty at the bunder is used for a passenger boat service that runs to Alibaug, but the bunder basin is over-crowded by fishing trawlers. Port officials confirmed that open plots have been illegally taken over by private individuals. According to port data available, there are as many as 14,365 structures on encroached dock land land spanning 7.46 hectares.

It seems that the port has a final chance at resuscitation after the report of the Land Development Committee, constituted last year by Union Minister of Shipping, Nitin Gadkari, is released. The committee, which was constituted with the idea of freeing up unused port land for public use, has suggested that 30 per cent of the land be used to satiate the city’s unending appetite for affordable housing, parks and transport links. Committee member and architect Hafeez Contractor imagines reclaiming several hundred hectares to build a sports city, theme park and water world, and what could be the world’s tallest building. “Most encroachments have come up due to ancillary activities that are carried out at the port; they haven’t sprung up overnight. The port must first carry out a survey of all encroachers and draft a housing policy to rehabilitate them. Without this, port development will not be complete,” says Mayuresh Bhadsavle, activist with Hamara Shaher Vikas Niyojan, a group that works closely with port communities.

Illegal berthing

Since the bunders don’t see leisure shipping activity, when a luxury yacht is parked where mooring is not allowed, it raises an eyebrow. Fantasea has been moored at Lakri Bunder Plot No. 7 for months, say insiders, with port officials unsuccessful at tracing its owner. They now suspect that it could belong to a resident of an adjoining slum on the water edge. “We think he is a hutment here, although on approaching him, he was dodgy,” says Zahir Kaji, port official in-charge of Plot No. 7.

Illegal parking is common at bunders.

Another vessel, Samrat has been abandoned by its owner at Reti Bunder. “This is over a 1,000 ton vessel that was carrying rock phosphate for unloading several years ago. We are losing Rs 40,000 in revenue every day as berthing charges,” admits S Tambe, official in-charge.

The docklands in numbers (**All measurements in hectares)

752.72

Total land owned by MbPT

2,676

Total leases entered into by the port

462

Number of lease agreements that have expired

14,365

Number of hutments

79

Number of plots at bunders

30.56

Total area of bunders

7.58

Area covered by road

11.88

Area leased out for industrial activity

Total cargo income at bunders

Rs 30.16 cr (2012)

Rs 32.97 cr (2013)

Rs 32.78 cr (2014)

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!