A remote Zilla Parishad school, powered by the resolve of its lone teacher, is teaching three-year-olds multiplication tables up till 16, and producing students who can draw and solve maths simultaneously

The school never shuts. If the teacher can’t take class, one of the senior students takes over. When the monsoon floods the village, it shifts to a tent on a hillock which is fitted with solar panels to generate electricity. Pics/Satej Shinde

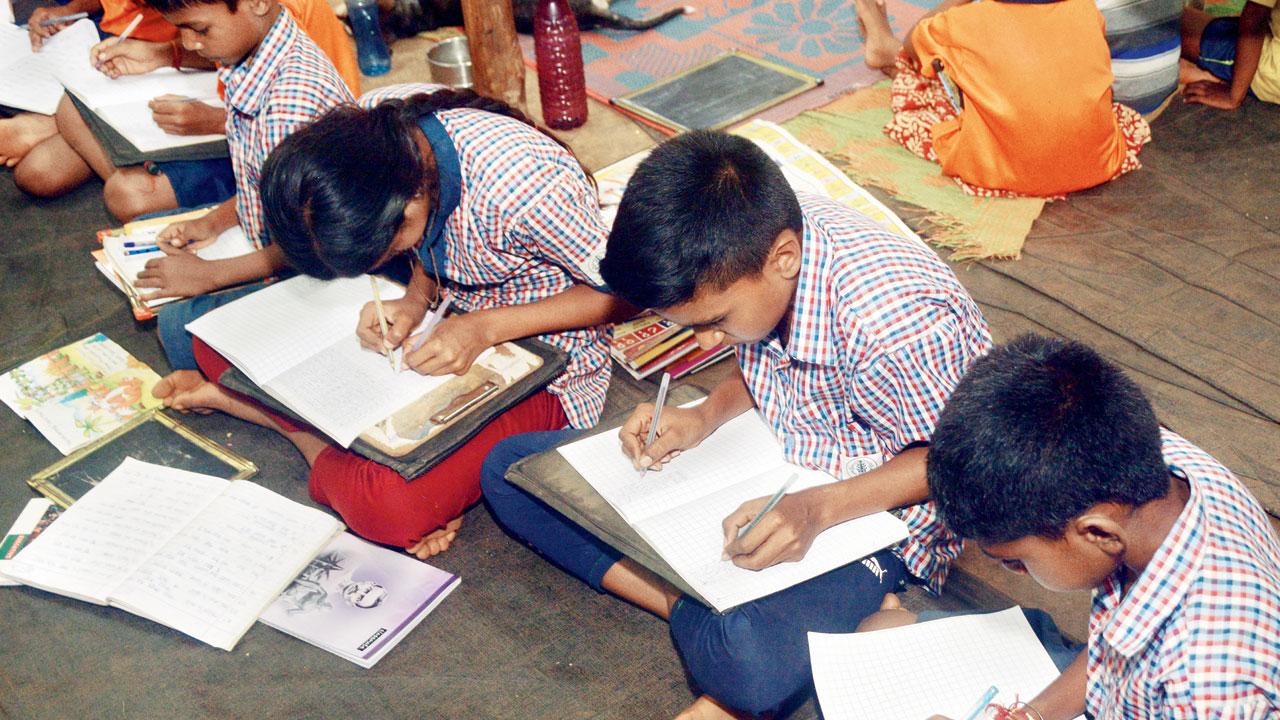

Students aged six to 13 write using both hands, and in two different languages; children in Class V to VII have multiplication tables up to 970 down to pat, sections of the Constitution are at the tip of their tongues, and solving a Rubik’s cube is as easy as connect-the-dots. Not blue-blooded pupils of an international school or private school, these children go to the Zilla Parishad school (ZP) in Nashik’s Hiwali village. And they can also name most highways and capitals of nations.

ADVERTISEMENT

This is thanks to their teacher, Keshav Gavit. Instead of a decrepit structure, the Hiwali ZP school is colourful, surrounded by lush greenery, and covered in educational posters inside and outside. “If a child’s attention wanders, everywhere s/he turns, they will only see educational material,” says Gavit. There are just two classrooms and two small rooms, one of which houses 150 to 200 books, and the other serves as a project room. The students paint and decorate the school with Gavit’s help. On a hillock close-by, they grow vegetables for their midday meal.

Children as young as three can rattle off multiplication tables up to 16; Class I and II students can take it to beyond 100

The school never shuts, and the learning does not slow down. If 36-year-old Gavit can’t take class, one of the senior students takes over. “We were closed only for a week during the pandemic,” says Gavit. “However, since “None of us travelled out of Thanapda or Hiwali; and on the parents’ insistence, we opened the school and followed social distancing and hygiene.” When the monsoons flood the village, it shifts to a tent on a hillock that is fitted with solar panels to generate electricity.

Also read: Uttar Pradesh: 2 arrested for possessing illegal crackers worth Rs 10 lakh

Nothing stops this march to progress. “Because of this school, our children have dreams that we never dared to dream,” says Haridas Usare, a farmer and daily-wage labourer. My daughter is in class X, and is already planning to become an IAS officer.”

Gavit was posted at Hiwali ZP School in January 2009. Armed with an MA and D.Ed degree, he was appointed to the primary school. The village did not have proper roads, and the school building was falling apart. The Zilla Parishad had no funds to help. He first tackled the structure, and raised money by contributing personally; the villagers and the NGO Give added to the kitty. Give also took care of stationary, uniforms and other educational paraphernalia.

Maya Shantaram Kirkire’s family doesn’t have a steady flow of income, but the 11-year-old is intent on becoming an IAS officer

“After this 30-35 mile stretch, hardly anyone knows about Hiwali,” says Gavit, who lives 13 km away in Thanapada. “There were no roads, no electricity, no phone connections, and water supply concerns. Shops selling necessities are 30 to 35 kilometres away.” Gavit trekked 16 km to and fro every day until 2016, over hilly terrain, to do his job. When pukka roads were finally laid, he could use transport.

The school had only nine students, of which many would join their parents in the morning to look for work. “Only four to five kids were regular,” he says. “I began with fundamental learning and writing exercises. After 2014, we had more children from Class I to Class IV. They could read and write not only Marathi, but also English.” He showed the villagers the difference in pace of progress of the children who were regular, to those who were not. This convinced the villagers to send their children to school. By 2016, the students were reciting multiplication tables. This caught the attention of the zilla parishad, which began encouraging and supporting them.

Gavit’s education encompasses life-skills such as solving the Rubik’s cube and general knowledge which boosts self worth. The children sing village songs such as the popular Bapu nana, Shembde nana. The older students teach the lower classes English poems.

The children of the school grow their own vegetables, which are then used to make their mid-day meals

When Kailash Pagare—an IAS officer and project director at Samagra Shiksha (Maharashtra)—visited the school last month, he noticed the children had brought art into their homes. “They painted Warli scenes on the walls of all the huts in the village.”

Maya Shantaram Kirkire lives with her parents and her little brother. Like all others, they don’t have a steady flow of income, but that doesn’t stop the 11-year-old from dreaming of being an IAS officer. “Our school is very beautiful,” she says.

“I get to learn new things every day and it’s our responsibility to decorate the school. We don’t sit in one place all day like in the other schools, we keep doing different things, and keep changing our places. When I become an IAS officer, I will not only solve the problems in our village, but also across the country.”

Gavit has taught all his students to be ambidextrous. They can also write in Hindi and English, simultaneously

Her friend Lalita Waghmare is also determined to better herself and her family’s situation through education. “My mother says there is no way we can have a better life if I do not go to school,” says the 12-year-old. “She’s right. I will be able to help my family only if I study and get a job. I hope I can help other students like me.”

But is it boring to study for nearly 12 hours every day? Pat comes the reply from class I student Darshan More: “Mala shalet khup majja yete; khau bheto, shikayala milta. [I have fun in school. I get snacks and I get to learn].” He can recite tables up to 55. Pagare was left speechless on his visit when a 13-year-old marched up to him and asked him how to become an IAS officer.

Gavit has taught all his students to be ambidextrous. But for those in Balwadi (kindergarten), practically all of them write using both hands. They can also write in Hindi and English, simultaneously. Some of them write with one hand while drawing with the other.

The only teacher at the school, Keshav Gavit, started teaching in January 2009. He is armed with an MA and D.Ed and lives in Thanapada

“We practise writing with both hands daily for an hour,” says 13-year-old Kiran Bhoye, who can write and draw at the same time. Three-year-olds, who start school, are encouraged to scribble with both hands. Gavit got the idea from the Internet. “I saw a video clip from Madhya Pradesh, which inspired my experiment,” he says. “They happily took to it, and needed to practice only for four-five month to master it. Now I want to answer two question papers simultaneously; they will finish their exam paper in half the time. It will be very helpful in competitive exams.”

Children as young as three can rattle off multiplication tables up to 16; Class I and II students can take it to beyond 100. Seven to eight children from Class IV and V students go up to 970.

“This helps us with mental maths, ‘’ says 13-year-old Maheswari Bhoye, who studies in class VII. “It’s tough initially, but once you know the tables up to 100 and 200, you know the trick to calculate quickly in your mind. The numbers start flowing once you practise every day. I couldn’t believe that I was able to multiply up to 970.” We asked her for a short demo with the number 969, and she was neither hesitant nor incorrect.

“The next goal is to know tables up to 1,000 by December,” says Gavit, and looks at the students. “YES!” they all agree. Gavit’s daughter Ananya, who just turned three, can answer 237 random general knowledge questions she and her father practice on their school run. These include capitals of state and countries, names of places, national animals and national heroes, national and international leaders, women achievers and mathematical questions. Kartavya, his nephew (also three years old), can recite tables up to 16 just like Ananya.

Important sections of the Indian Penal Code, and clauses from the Constitution are written on the walls of the small room that serves as the school library. A seven-year-old can tell you more about a particular IPC section or constitutional clause as well as a 13-year-old. “Zilla Parishad officials and other visitors are astonished how students have these at the tip of their tongues, when randomly,” Gavit makes no effort to hide the pride he takes in his students. He encourages them to read different kinds of books, because of which they are ahead of their age and grade on the learning curve.

Prakash Bhivsan, the local head of the Schools Management and Improvement committee bears witness to these achievements. “Ten years ago, I would not have believed this was possible,” he says. “We have seen their talents grow and skills progress. Our students are on par with those of any urban school.”

“I had heard about this school,” says Pagare, “and we promote similar case studies through Samagra Shiksha. On my visit last month, I was left impressed by the abilities of the students. It shows how a teacher’s efforts can transform a [brick-and-mortar] school, students, and even a village, regardless of the remoteness of location and lack of resources. The aim of my visit was to determine strategies or methods which can be replicated in other schools. I had planned on staying for half-an-hour, but ended up spending three hours talking to them and watching their skills. Their cursive writing is so neat and beautiful.”

In 2019, the NGO Give took two girls from the school to Nashik city, where a coach taught them how to solve the Rubik’s cube. Those girls, in turn, taught the others in school. Most students, save for those in kindergarten, can harmonise the cube in less than two minutes; a few just need one.

“Even I can’t solve the Rubik’s cube yet,” admits Gavit. “But these kids need no effort at all. The little ones just play with it for now, but I’m sure they will learn it very soon too. The [mental] exercise helps them focus and stay determined. They can apply that to studies too.”

Vaishali Veer, the district Education Officer for Nashik and Deputy Director of Maharashtra Prathamik Shikshan Parishad (MPSP) Mumbai says the school is a model for others. “The progress of the Hiwali ZP School is due to years of effort and determination by Keshav Gavit,” she says. “The students’ enthusiasm and active participation by villagers have brought about the kind of transformation elite urban schools may want to study and replicate. Located in such a remote and backward region, these students are a ray of hope for many.”

Where is Hiwali?

Hiwali is an adivasi pada (tribal village) located near the Maharashtra- Gujarat border. It is roughly 80 km from Nashik city, and has about 30 houses inhabited by 45 families. The 215 people belong to Kokna and Mahadev Koli tribes. No one in the village has a permanent job; they rely on farming and temporary employment to make a living.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!