A political science lecturer at Wilson College and the man behind its four-decade-old nature club sparks a conversation around our yearning for 'dramatic' sightings on safaris and why one life is too short to experience India's biodiversity wonders

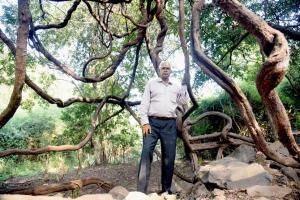

Sudhakar Solomonraj visits Kanheri caves inside Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Borivli, twice every month. It's where you

Sudhakar Solomonraj censures himself in an initial chapter titled Fears and Tears in his 160-page just released book, Living Nature. He admits being ineffective and impatient in dealing with the irrational fears of fellow trekkers towards insects, animals and other forest beings. He was unable to identify with nyctophobia or the fear of darkness that some experience on night excursions. Also, he could not easily empathise with the trauma visitors experienced with leeches, which made them unwilling to "give another chance to the forest". Indian cities are unfortunately, way too sanitised to allow us familiarity with various life forms, putting the responsibility on nature club organisers, like himself, to counsel the uninitiated who run the risk of killing a snake or spider out of fear.

Sudhakar Solomonraj censures himself in an initial chapter titled Fears and Tears in his 160-page just released book, Living Nature. He admits being ineffective and impatient in dealing with the irrational fears of fellow trekkers towards insects, animals and other forest beings. He was unable to identify with nyctophobia or the fear of darkness that some experience on night excursions. Also, he could not easily empathise with the trauma visitors experienced with leeches, which made them unwilling to "give another chance to the forest". Indian cities are unfortunately, way too sanitised to allow us familiarity with various life forms, putting the responsibility on nature club organisers, like himself, to counsel the uninitiated who run the risk of killing a snake or spider out of fear.

ADVERTISEMENT

Solomonraj is the founder of the 40-year-old Wilson College Nature Club and was feted by Sanctuary Asia as Green Teacher in 2010. The man from Chennai joined the college as an undergraduate student in 1978 and has been associated with it since. In Living Nature (Notion Press, R799), whose foreword he signs off as "The Crazy Old Man", Solomonraj, 55, revisits journeys he has taken over four decades. During this time, he has been part of close to 100 camps and 250 trails. Photographs, research notes, maps and graphics that find their way to the book have been contributed by students and colleagues, who have continued to be part of the club even after leaving college.

Living Nature speaks of Solomonraj’s many sightings, including what the non-dramatic animals and reptiles like the Gaur and Bombay bush frog. Pic courtesy/Ameya Gokarn and Prachi Galange

Living Nature doesn't just recall the thrill of the outdoor, it builds conversations around biodiversity and wildlife, thereby putting the onus on the individual to conserve and celebrate bio hotspots. Solomonraj goes beyond being a wilderness admirer. He is the espouser of causes of retaining natural habitats, whether Kerala's Silent Valley Movement or Gujarat's Narmada Bachao Andolan. His MPhil dissertation was centred on the Chipko movement of the 1970s. His personal involvement lends weight to the climate control solutions he offers in the book, whose pages are made of recycled paper. He advises behavioural changes that will help us curb water and food wastage; his large family of students quote instances of his strong insistence on smaller meal servings and the judicious use of potable water when on nature trails.

Living Nature rests on an appeal to keep all your senses open to stimuli, so as to enable a joyous observation of tree shapes, flower sizes, butterfly movements, bird calls, the sound of crickets, soil quality and of course, the star-lit sky. He references several star gazing sessions that have added a new dimension to his adventures. Trails are not meant to be botany and zoology excursions, umpired in correspondence with the number of sightings. In this context, Solomonraj discourages high-maintenance vehicle-driven wildlife tours centred around the "tiger-dekha-kya?" excitement. This objectifies the tiger, he argues, without making it a part of a wondrous ecosystem. In the 1990s, it was quite usual for forest rangers on elephants to radio the location to their colleagues if they'd spotted a tiger. It ensured that the visitor demand was met. However, Solomonraj recalls, on one WWF camp in Kanha, voice was raised against the disturbance to the tiger. The slogan, Yeh National Park Nahin, Yeh Mera Ghar Hai, emerged from steady campaigns against noisy interventions of those who want to experience wilderness in templated formats.

Solomonraj shares the dilemma of the nature trail organisers. For instance, once he walked with a group of first timers to the thicker part of the Munnar forest in Kerala. He was excited to see the endangered Nilgiri tahr; but one student quipped, "we walked 11 km to see goats?" The reaction was similar when passing through Periyar from the Kallidaikurichi site. The participants couldn't appreciate the exhilaration of spotting a troop of Nilgiri langurs. The author says, not just first-timers, but seasoned professionals also react insensitively. About 10 years ago, when he had visited Kutch, he made a special note of the Asiatic wild ass, to which a colleague said, "Akhir gadha hi toh hai." Small wonders (herbivores) do not excite campers.

Living Nature sensitises the reader to the riches that are not apparent to the eye. In one of the political science field visits, his group chanced upon the Glory of Allapalli (between Gadchiroli and Bhamragarh), Maharashtra's first bio-heritage site, which they were oblivious to in 2013. While the region's large trees (teak, tendu, temburui, dhawda and kusum) and aquatic birds piqued their attention, it was only after subsequent visits that they realised the worth of the hotspot. The moot point is to keep the mind open to experiences beyond selective occasions—whether it is langurs, peacocks and black bucks around Akbar's tomb at Sikandra near Agra, the spotted deer near the massive stupa of Sarnath, the long-tailed mongoose at Ranthambore Fort or leopards at Kanheri caves in Sanjay Gandhi National Park.

The book presents all the Indian states with their bird sanctuaries, nature parks and tiger reserves mapped. Pic courtesy/Living nature

Speaking of Maharashtra, Solomonraj says he is enamoured by the rare rock gecko specifically seen at the Kanheri site. Bats, bees and snakes witnessed around caves and large-roofed structures are equally exciting. Maharashtra has the largest number of hill forts and, therefore, offers some of the best sightings of the Peregrine falcon, memories of which he holds central to his wilderness exposure. In 1984, he handled aplysia or the sea slug on the rocks next to Kulaba fort in Alibaug. He has spotted and handled jellyfish like the deadly Portuguese man o' war before realising its painful sting. His encounters with starfish octopus, sea snakes, turtles constitute zen moments. So, does his rapport with birds—curlews, snipes, plovers, terns and other waders. He particularly values watching the magnetic flight of a white bellied sea eagle at Colva beach in South Goa two months ago.

Are you a mountain person or an ocean person? This is a question Solomonraj asks, according to which he recommends trail sites. He presents all the Indian states according to their bird sanctuaries, nature parks and tiger reserves. The book is loaded to a fault in terms of possibilities—each page suffused with green getaways and public precincts that can be accessed by anyone.

Since one lifetime is just about adequate for exploration, the countdown begins now.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar @mid-day.com

Catch up on all the latest Crime, National, International and Hatke news here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!