At 83, Pune-based activist-author Sayed Mehboob Shah Quadri is winner of an award from Chaturang Pratishthan for five decades of work against the instant talaq-e-biddat, but he says he is far from done

Sayed Mehboob Shah Quadri will receive the Lifetime Achievement Award from Chaturang Pratishthan this month for his work to empower Muslim women by challenging gender-skewed traditions. Pic/Nithin Mohan

Sayed Mehboob Shah Quadri—Sayedbhai for those who love and respect him—is a reformist movement in himself, one that flows uninterrupted, but without magical speed. Little wonder that after sustaining a five decade-long campaign against triple talaq, the Pune-based activist-author, who is co-founder of Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal, doesn't wish to call it a day. Instead, at 83, he longs to see a time when Muslim women will speak up for their rights. A week before he is to receive the Lifetime Achievement Award in Nasik from Mumbai-based cultural organisation Chaturang Pratishthan, for his efforts to end the unjust marital practice, he says, "I am waiting for greater change in the everyday lives of Muslim women, and a vision that brings us closer to ideal gender equality."

Sayed Mehboob Shah Quadri—Sayedbhai for those who love and respect him—is a reformist movement in himself, one that flows uninterrupted, but without magical speed. Little wonder that after sustaining a five decade-long campaign against triple talaq, the Pune-based activist-author, who is co-founder of Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal, doesn't wish to call it a day. Instead, at 83, he longs to see a time when Muslim women will speak up for their rights. A week before he is to receive the Lifetime Achievement Award in Nasik from Mumbai-based cultural organisation Chaturang Pratishthan, for his efforts to end the unjust marital practice, he says, "I am waiting for greater change in the everyday lives of Muslim women, and a vision that brings us closer to ideal gender equality."

ADVERTISEMENT

Sayedbhai's wait for a better social climate dates back to the post-Tilak Pune of the 1940s when his family shifted from Hyderabad in search of livelihood. At the impressionable age of four, he descended on one of Pune's military tenements along with five siblings. While his father worked at a British officer's bungalow, his elder brother and mother took up odd jobs. A formal education for the children was not an immediate priority, but little Sayed got admission to a free Urdu school on Moledina Road. The Sayeds slowly secured a toehold in a city whose fuel came from a strong anti-British nationalist sentiment. He recalls the first time that the Indian tricolour was unfurled by the Khadki Cantonment Board officers. Children of neighbouring Marathi and Urdu schools gathered to see the Ashok Chakra replace the crescent moon.

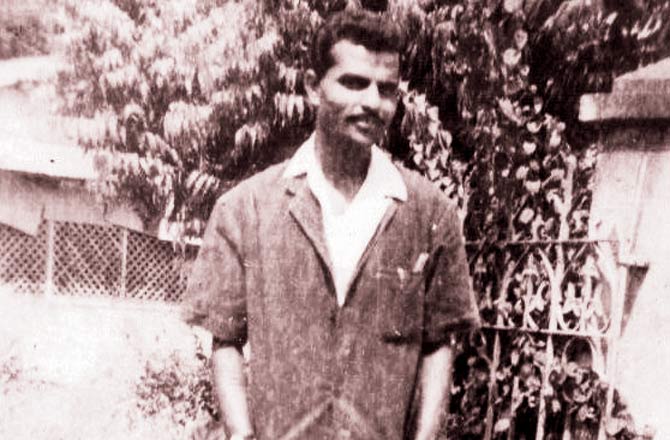

At Bharat Pencil Factory in Pune, 1965, which he joined as a 13-year-old

Even as sweets were distributed to celebrate the moment and Sayedbhai had his own personal victory of standing first in four classes, to be happy about, the schoolboy's joy was short lived. Free Urdu education was now behind him, and he'd have to pay the fees to make it to class five at a Marathi medium school. He tried his luck with night classes, but ended up looking for jobs at various industrial units. He would stand at the gate of National Chemical Laboratory, then newly inaugurated by Jawaharlal Nehru, and inquire about a vacancy. He later recalls the "gate act" as an unwise and sentimental response to unemployment. At 13, he joined the Bharat Pencil Factory as apprentice, where he not only learned every pencil-making function there was, but became owner Tatyasaheb Marathe's closest aide. As operational head, his responsibilities grew four-fold, which is why he couldn't ever take study leave, not even for the matriculation exam. Later in 1997, he started his own incense stick factory, which he runs to date. "I feel I was destined to learn in what I famously call the binbhintichi shaala, the school without walls, which adjusted to my mistakes and experiments."

While Sayedbhai was happy to train as pencilmaker, the year 1957 set him off on a social crusade that he was not prepared for. His 18-year-old sister, Khatija, was deserted by her husband. She returned to her maternal home with two children. Sayedbhai could not accept the logic behind zubani talaq. How could a man leave his partner by uttering three words?

The founding members of Muslim Satyashodhak: Quadri, Hamid Dalwai and Babumiyan Bandwale

This question became the focal point of Sayedbhai's life. At 20, he decided he'd work towards two goals—make his sister financially independent by enrolling her at a tailoring class, and let her discard the burqa. The second goal, a more ambitious one, was to create an ecosystem where verbal divorce could be ended.

Khatija triggered Sayedbhai's innings as a reformist. Despite opposition from the community, he was outspoken about his radical idea of Islam. On every available social platform, he collaborated with ideologues and thinkers of the day. He spent hours with Bhai Vaidya, Anil Awachat, Kumar Saptarshi and other Pune intellectuals to discuss the possibility of a uniform civil code. In this phase, when he was seeking appointments with anyone who could add a perspective to the talaq issue, he was introduced to reformer-orator-writer Hamid Dalwai.

Quadri (at mic) at the All India Forward Looking Muslim Conference, New Delhi, 1971

Little did Sayedbhai know that he would end up being part of Dalwai's secular reformist age of questioning. "I was in search of a guide and Hamidbhai's entry in my life [1968] opened new avenues for me. I feel fortunate to have been part of the Muslim Truth Seeking Society that Dalwai floated. He dared to speak the truth about the situation of Muslims in post-Independence India that few wanted to hear." Dalwai requested Indian Muslims to respect and recognise the Indian Constitution as a document that was above all religious texts. Whether polygamy, birth control or adoption, he did not seek answers for social issues in the Quran. When Dalwai died a premature death at 44 in 1977, Sayedbhai was among those who was by his side till the very end. "A section of Muslims distributed pedas after his death. It was a tough fight which continued after his death. I am glad to be part of the history he made."

Sayedbhai says he has counselled 3,000 Muslim women and families in and out of Pune, all affected in some way by the triple talaq tradition—the pencil and agarbatti factory units doubling up as venues for therapy sessions.

For him, life continues to revolve around rich conversations. He rarely misses an opportunity to discuss the status of Muslim women, whether with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whom he met in February this year, or former PM Rajiv Gandhi, whom he met in 1986 as part of a delegation that was to discuss the government's role in the controversial Shah Bano maintenance lawsuit. In fact, he invited Shah Bano to Pune for a public event, at a time when Muslim mainstream opinion was against the Supreme Court judgment favouring maintenance for the divorced woman.

Sayedbhai sees the latest Chaturang Pratishthan award as a conversation starter, too. "The honour given by a mainstream cultural group, which does work in a different social realm, means a lot. Its past recipients include dramatist PL Deshpande and scientist Jayant Naralikar. I am happy to be in their league."

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Catch up on all the latest Crime, National, International and Hatke news here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!