Sahitya Akademi's Bhasha Samman winner and Vedic researcher Dr Madhukar Mehendale, is inspiration to contemporaries and his family as he turns 100

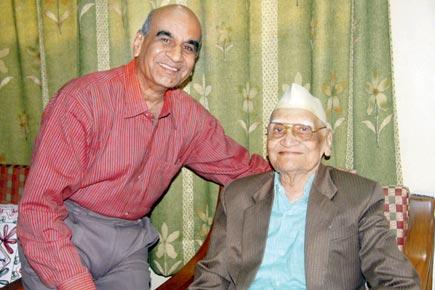

Dr Madhukar Anant Mehendale's elder son Pradip says he is inspired by his father's joie de vivre for life and learning. Pic/Mandar Tannu

ADVERTISEMENT

Indian currency notes and official documents flash the inscribed motto, Satyameva Jayate (Truth Alone Triumphs). The catchphrase, however, is not true to the context in which the maxim is used in the Mundaka Upanishad. Contrary to the popular paraphrase, satya here means the final inescapable truth (and nothing but that) that a seer or rishi attains.

Indian currency notes and official documents flash the inscribed motto, Satyameva Jayate (Truth Alone Triumphs). The catchphrase, however, is not true to the context in which the maxim is used in the Mundaka Upanishad. Contrary to the popular paraphrase, satya here means the final inescapable truth (and nothing but that) that a seer or rishi attains.

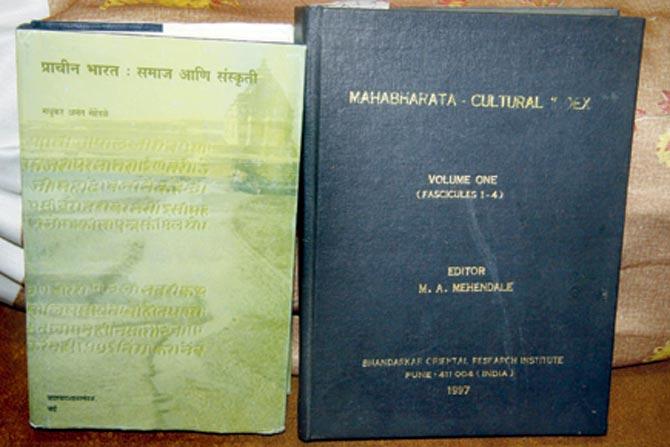

It is not surprising that this truth was underlined by Dr Madhukar Anant Mehendale, a Vedic scholar and the recipient of the Sahitya Akademi's Bhasha Samman. He won the award recently for his contribution to classical and medieval literature with special reference to Sanskrit, Prakrit, Rigveda, Nirukta, MahÄu00c2u0081bhÄu00c2u0081rata and the AvestÄu00c2u0081.

Dr Mehendale is known for intellectual pursuits that few can undertake. He has upturned popular idioms and questioned flawed but deep-rooted beliefs; analyzed texts to assess trends, not to forget his original observation that Sanskrit poetry carries copious descriptions of a woman’s anatomy, but invariably leaves out the nose. He has identified parallels in seemingly dissimilar scriptures, like the Hindu Rigveda and Zoroastrian religious text, Avesta.

Dr Mehendale is known for intellectual pursuits that few can undertake, including identifying parallels in seemingly dissimilar scriptures, like the Rigveda and the Avestaa

While dissecting the Mahabharata, he called Draupadi's vastraharan a hyped tale. He explains in his 45-minute biographical documentary titled, Dr Madhukar Anant Mehendale, that the Pandavas lost a crucial game of dice against the Kuaravas, and with it they lost their right to wear the Uttariya vastra or upper garment. Dushasana asked them to take off the upper robes. Draupadi, being their wife, must have been asked to follow suit, which does not suggest that she was stripped, as portrayed in pop art.

And so, there is a joke that does the rounds of the Mehandale residence in Pune's Kothrud neighbourhood. If you ask Appa the meaning of a proper noun, his answer will not be instant, but an exhaustive cyclostyle note on the word's origin, popular usage, its reference in the scriptures and contextual undertones.

Although Dr Mehendale at 99, is not the active person he was until a year ago — known to use public transport until he was 97 —he is intellectually available and open for interaction, as was evident when the media sought him out after the Sahitya Akademi honor. To this writer's question on how he feels to be turning 100, his answer is succinct: "People say age is a figure. But it is more than a numeral. I see age as a collection of experiences; accumulations of all that you have lived in diverse phases."

Diversity is abundant in Dr Mehendale's life, which began on February 14, 1918 in Harsud, Madhya Pradesh. He schooled in Baroda and Indore, studied at Mumbai's Wilson College and his doctoral research thesis (Historical Grammar of Inscriptional Prakrits) was completed at Pune's Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. He taught at Basaveshwar College in Bagalkot and later at SB Garda College in Navsari. He was invited to the Göttingen University in Germany back in the early fifties to complete the unfinished work of German scholar Heinrich Luders on Prakrit inscriptions.

Despite the peripatetic life, Dr Mehendale has been a Punekar at heart. He guided research students and edited the Dictionary of Sanskrit on Historical Principles at Deccan College right up till the eighties, where his late wife Kusum, a Gandhian, worked as a librarian.

In fact, after retirement, Dr Mehendale worked for 25 years at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute as the indefatigable Chief Editor of the Cultural Index of the Mahabharata. As his daughter-in-law, Rohini Mehendale, 66, says, no one in the family is allowed to feel old or retired. "He keeps us young and reminds us that there is a lot still to be accomplished." She recently wrote Mee Ek Sanik Patni (Myself, A Soldier's Wife), a book in which she acknowledged Dr Mehendale's inspiring presence at home.

Her husband and Dr Mehendale's son Pradip, 71, is retired Army colonel, who says, "Appa has an interesting reading routine for himself — a certain stotra or shloka chalked out for a certain day, a particular scripture for a particular season. It's not that he is an overtly religious person, but he likes to connect with people and practices."

Interestingly, ever since senior Mehendale has been unable to walk in his locality, he has replaced it with an evening stroll on his wheelchair. And the bite of a pani puri and a sip of sugarcane juice while he is at it, continue.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@gmail.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!