For a city left with few standalone theatres, what did Rex, Defence and Edward exemplify in the epic age of single screen cinemas?

Sanjay Vasawa, former manager of Edward Talkies on Kalbadevi Road, opening to the public in 1914. Pic/Suresh Karkera

Stardust memories flooded my mailbox in a swoosh. Responses to last month's column from readers recalling their carefree, happiest hours spent in single screen cinema halls. One of them missed mention of Rex, Defence and Edward. That piece, on BEST bus journeys of younger years, was limited to movie houses I frequented when studying at St Xavier's College.

Stardust memories flooded my mailbox in a swoosh. Responses to last month's column from readers recalling their carefree, happiest hours spent in single screen cinema halls. One of them missed mention of Rex, Defence and Edward. That piece, on BEST bus journeys of younger years, was limited to movie houses I frequented when studying at St Xavier's College.

ADVERTISEMENT

But her message made me curious to know the stories behind this trio of theatres.

View of the interior where an orchestral music pit beneath the stage is still intact

Winning a lottery and then a horse race started it all for the Bhavnagris, who built Rex opposite Ballard Pier's Red Gate in the late 1930s. They got to Rex interestingly, after laying roots in Derby, their first cinema. Jehangirji Bhavnagri and his son Shapoorji worked at an Indore mill. Buying a lottery ticket with the British boss, they struck luck. When the Brit refused them their portion of prize money, they sought legal opinion and the court ruled favourably.

Jehangirji looked for an investment opportunity. There was also the sum he had won betting on Windsor Lad, belonging to the Maharaja of Rajpipla. The Irish thoroughbred galloped to victory at the 1934 Epsom Derby and Jehangirji erected his theatre named Derby the next year, informs a Bhavnagri grandson—"Derby's earnings were ploughed into Rex. The third theatre, Diana at Tardeo, displayed the Roman huntress-moon goddess above our stage."

Windsor Lad, owned by the Maharaja of Rajpipla, winning the Epsom Derby in 1934. Having bet on this horse, the Bhavnagris named their first cinema Derby, before building Rex

Proximity to the docks made Rex popular with a swell of patrons. An old booking clerk remembers curtains flap outside the auditorium and "Welcome" blaze across the main red velvet curtain within, riding up silkily for the film to unreel. Besides Hindi hits, towering among such mega releases of the 1960s-'70s as Satan Never Sleeps, The Night of the Generals and The Omen, was The Guns of Navarone. The 1961 war epic was the smash success from flicks at Rex based on Alistair Maclean novels like Where Eagles Dare and Fear is the Key.

Hallowed spot that Rex was for spaghetti westerns, House Full placards covered posters of Sergio Leone's Dollars trilogy, loved for the game-changing twangs of eternally hummable theme tracks Ennio Morricone scored. United Artists' campaign strategy, branding anti-hero Clint Eastwood "the man with no name", saw him dubbed Joe in A Fistful of Dollars, Manco in For A Few Dollars More and Blondie in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

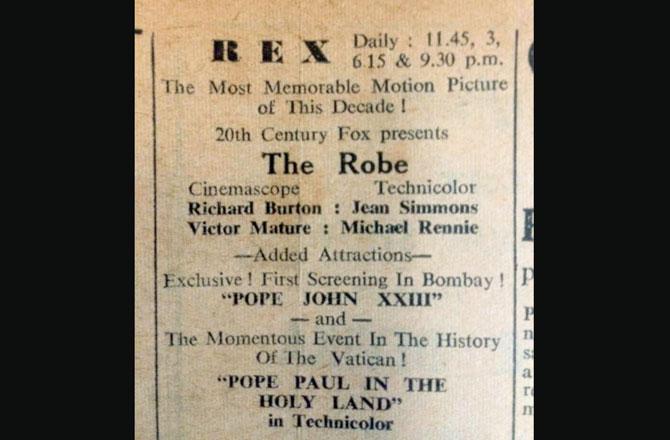

An advertisement dated November 27, 1964 announces Rex shows for The Robe, "The Most Memorable Motion Picture of This Decade". Pic courtesy/Deepak Rao

This was where urban chronicler Deepak Rao devoured spy sagas like That Man in Istanbul, formulaic of the Cold War era, less glamorously aping the James Bond franchise. "A fingerpost to history, Rex rose under the hold of Empire," he explains. "Iranis called their cafes Lord Irwin and Brabourne. Cinemas were Imperial, Regal, Edward and Empire."

Rex played a poignant part introducing an iconic Churchgate restaurant. How Tulun Chen came to possess the Cantonese-Hunan eatery is an account warmer than the soup bowls that steamed up his tables. Crossing the road after a show of The Guns of Navarone, 18-year-old Chen and his friends saw an elderly Chinese man knocked by a cab and admitted him to hospital. The accident victim recovered, revealing he was KC Tham from Hong Kong. They somehow pooled money for his R3,000 sea passage back. About to sail, the gent pressed a piece of paper into Chen's hand, whispering, "This is yours." Gratitude for the so-very-Bombay kindness of strangers, it was the sale deed for Kamling, which opened in 1939-40.

Jehangirji Bhavnagri and his son Shapoorji; (right) Jehangirji opened Rex at Ballard Estate in the 1930s

Unfamiliar for many, south-tipping Defence near RC Church was commissioned as a storehouse for bulk items and unserviceable spent cartridges in 1924, the year landmark Colaba Garrison structures like Gun House came up. Troops were entertained under its sloping roof from 1932. The recreational hub, screening films from 1955 on a heritage "wall", was christened Defence in 1974. Functioning decrepitly for a few decades, the refurbished avatar, Sena, since 2004, has surround sound and air conditioning.

In "Remembering Anthony Gonsalves", for Seminar magazine, Naresh Fernandes links the Garrison to Chic Chocolate, from years the musician led an 11-piece jazz band at the Taj and lived in 1960s Colaba. "The flat had one bedroom but two pianos. Chic couldn't resist another after he found Mehboob Studio was selling it for just Rs 200… Chic's career was tragically short. He died aged 51. His casket was borne by Bombay's foremost musicians, including accordion player Goody Seervai and drummer Francis Vaz, his Selmer trumpet placed across his chest. Shortly after, Chetan Anand's Aakhri Khat hit the screen. The bluesy song 'Rut Jawaan Jawaan' featured several close-ups of the Louis Armstrong of India playing trumpet solos from the bandstand. Whenever they missed his presence, Chic's children would go to Garrison theatre to commune with their father."

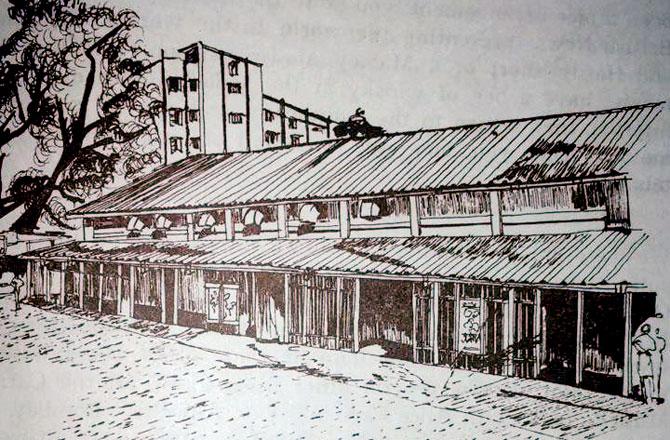

Garrison Cinema sketch by Dilshad Faroodi. Reproduced from Ah! Colaba (1989)

As a boy, journalist Farrokh Jijina was dispatched by his mother, on the Thursday holiday from school, to reserve advance seats for Saturday evening shows at Defence. Weekends welcomed civilians to this space, otherwise for the Forces. "A tongue lashing awaited if I returned bringing tickets wet with rain or limp from any moisture. What to do, they were stamped on the flimsiest barfi pink paper," he laughs, remembering being besotted by Rajesh Khanna in Aan Milo Sajna. "We'd troop down from Cusrow Baug to settle in cushioned chairs of the last three rows, far from bug-infested wood front benches. Visits weren't complete without samosas ingested with the ink of notebook pages wrapping them, their spice washed away by sweet sips of mud coloured Vimto."

Helpful retired officers volunteer information spanning the hall's Garrison-Defence-Sena journey. "Predominantly for Hindi film re-runs, Defence had the odd English or regional language Sunday morning show," says Commander Mohan Narayan, former curator of the Maritime History Society. "With digital prints, the Forces enjoy newest releases in a daily show and two on Sundays."

Renamed Defence, the theatre got its present name, Sena, in 2004. Pic courtesy/Swords and Shield, published by HQ M and G Area

Post-terror strikes, the sensitive area remains off-bounds to the public, though civilians within military cantonment confines and Navy Nagar are permitted. In days of a general undisciplined public, wild whistles and whoops would greet certain songs. People apparently pelted piles of coins at the screen, flashing the qawwali from Dharma, "Raaz ki baat keh doo toh", focused on Pran and Bindu. "In exquisite irony, an Army-owned cinema has always been used more by the Navy," observes one veteran commodore. "Paying cheap rates, we can without regret walk out of lousy films or go in as soon again to repeatedly catch sequences."

Evolving a little like Defence, albeit much grander in scale and decor, Edward Talkies graces Kalbadevi Road from 1914. Initially, the 19th-century venue regaled expats and soldiers with live performances. An orchestral pit still exists in this, probably our oldest surviving single screen gem, as do massive entranceways which brought through backdrop props. Bordered by fading but beautiful white and pastel blue trimmings, the triple-tier interior accommodates 509 viewers in Orchestra, Dress Circle and First Class.

Chic Chocolate trumpeting "Rut jawaan jawaan" in Akhri Khat. After he died, the musician's family in Colaba often watched this song sequence in the film's run at Garrison

"I watched American cowboy movies as a kid in the time of my grand-uncle Bejan Bharucha," says Fred Poonawala, running Edward today with his cousins. Bharucha reached Bombay from Bharuch, Gujarat, for a job as a barman at the Taj, before establishing himself as an exhibitor and theatre proprietor. When he passed on, his German wife Gertrude took over, keeping ticket prices the lowest possible for poor neighbourhood labourers and beggars to afford moments

of escape.

Around Edward's formal unveiling as World War I broke, cinemas began to be described as "picture palaces". Delighting film buffs with its grandeur, the theatre was as well a platform for advocacy where citizens gathered for speeches like Gandhiji's addressing grain merchants during the Independence movement. Edward flit from Flash Gordon-type action series to B-grade Bolly to avant-garde European festival circuit fare. Factoring the vicinity's once hefty Catholic and Parsi population, it periodically aired Cecil B de Mille blockbusters like The King of Kings, a stellar attraction for these communities.

"What cinema history was created in 1975," declares Sanjay Vasawa, ex-manager of the cinema. He means the months of Jai Santoshi Maa's benign reign, catapulting to superstardom a heavily adorned, and adored, Anita Guha cast in the title role. Her idolisation, verging on worship, asserted how the belief system of mill workers and cinemagoers shaped the city's social fabric. Clapping, crying, chorusing bhajans, they contributed a dream year for Edward. Fans folded hands in tearful prayer to strains of "Main toh arti utaru re Santoshi Mata ki".

Vasawa adds, "We had throngs of thousands press against the ticket window. Treating the cinema as their local temple, Gujarati and Maharashtrian housewives removed their chappals at the threshold. Carrying puja thalis, they entered barefoot, lit diyas when Devi Ma appeared on screen, and even distributed chana and jaggery to other devotees." Like his father Hiralal for long years before him, Sanjay considers the Edward green room his home.

Crumbling, yet struggling to muster dignity amid redevelopment, these cinemas lent character to the horribly homogenised scape that sullies our gullies. We miss feeling alive from the flutter of sitting in squeaky seats with robust audiences in packed halls. Anticipating thrills heralded by static crackle from the projection room after ruched curtains swung softly up. Hoping a greater number of reels counted on the censor certificate ensured a longer watch. For sure, the words "The End" have never rung sadder than now.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher

marfatia.com

Keep scrolling to read more news

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and a complete guide from food to things to do and events across Mumbai. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates.

Mid-Day is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@middayinfomedialtd) and stay updated with the latest news

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!