A confluence of Gandhian, Tagorean and theosophical thought, The New Era School pioneered humanism and art bred by pre-Independence India’s renaissance years

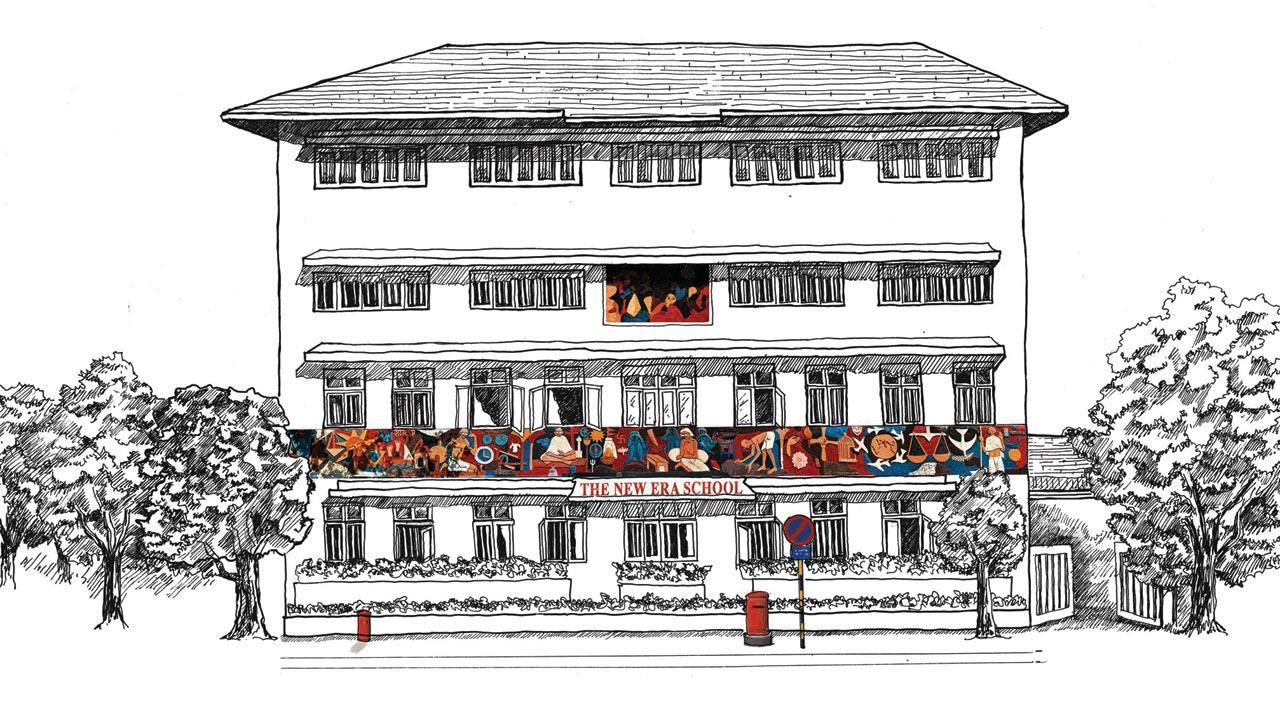

New Era School on Hughes Road, illustrated by Shital Mehta. Pic Courtesy/The New Era Odyssey

I loved school so much, I pretended to be well when I was sick, so that I didn’t miss going.” Not an unimaginable ploy when you realise Darshana Shilpi Rouget, now an art director in London, went to The New Era School.

I loved school so much, I pretended to be well when I was sick, so that I didn’t miss going.” Not an unimaginable ploy when you realise Darshana Shilpi Rouget, now an art director in London, went to The New Era School.

ADVERTISEMENT

Guided by visionary principals, the essentially child-centric and life-affirming ethos of this school attracted pupils even during vacations. It joyfully embraced progressive thought, shunning early 20th-century authoritarian notions of education.

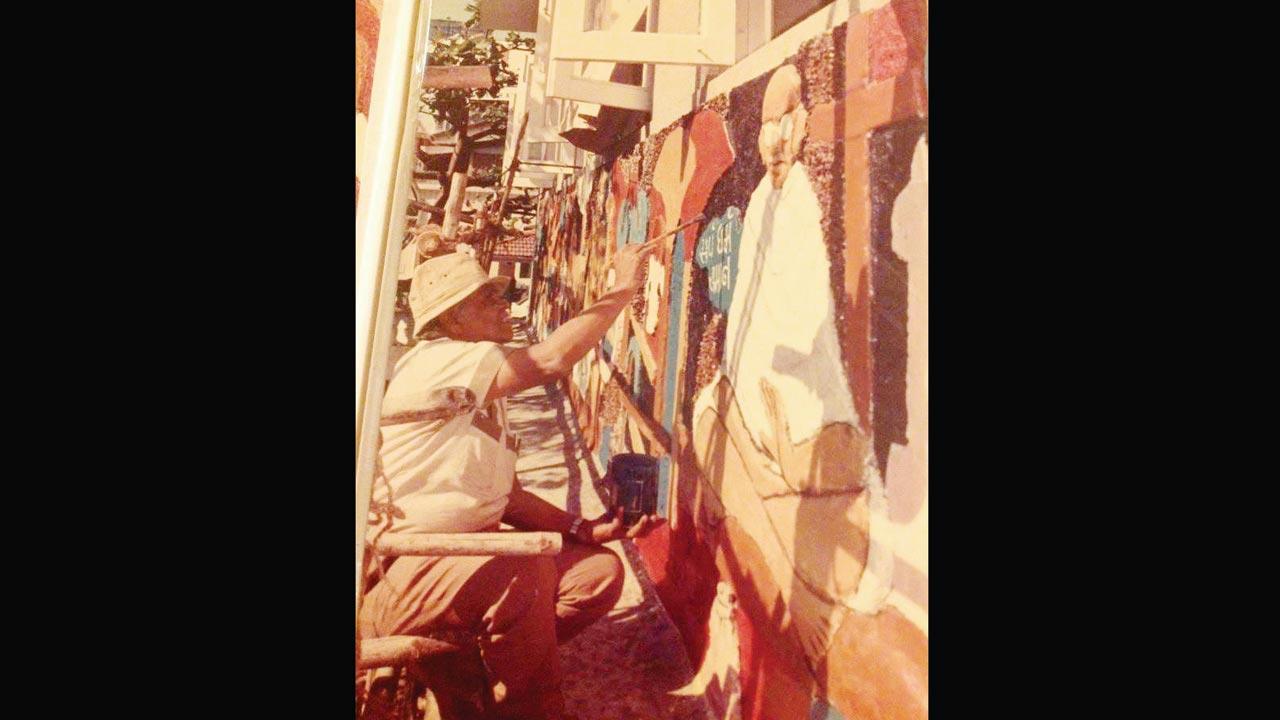

Art teacher Dinesh Shah working on the facade mural in 1969. Pic Courtesy/Paula Mariwala

Art teacher Dinesh Shah working on the facade mural in 1969. Pic Courtesy/Paula Mariwala

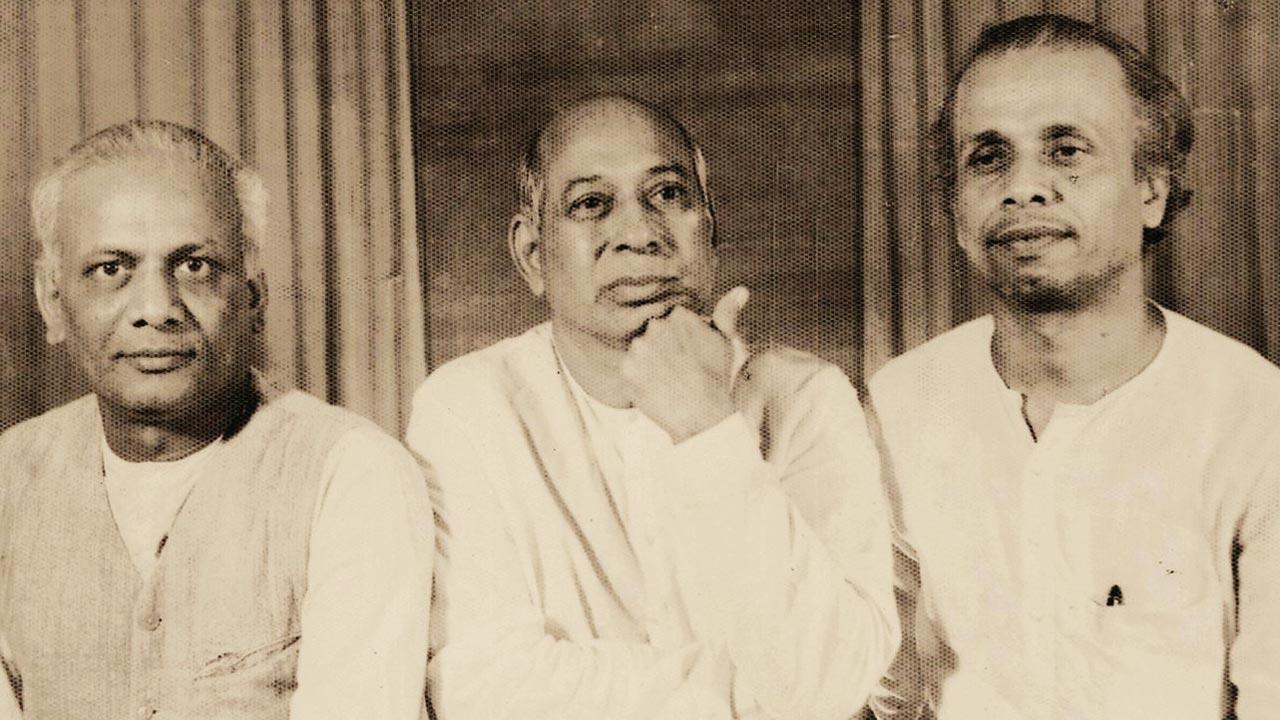

Exemplary educators, Maganbhai Vyas (widely known as MT) and his brother Chandulal, from Rajpipla in Bharuch district, were considerably impacted by Annie Besant’s Theosophical Society. Trained in its worldview by George Arundale at Adyar, they started an ashram school on the banks of the Narmada in 1922. Two years later, MT attended the London School of Education.

Returning, MT was inspired by Gandhiji’s Nai Talim (new education). Aligning its precepts with the all-encompassing lessons of Shantiniketan, the Vyas family established the co-educational Fellowship School in 1927 and, nearby on Hughes Road, New Era in 1930. MT declined the post of Deputy Director of Education, till then offered only to Brits. He was determined to spread schooling seeped strong in indigenously brilliant political and artistic soil.

Teacher Somnath Patel, founder principal Maganbhai (MT) Vyas and music head Pinakin Trivedi from Shantiniketan. Pics Courtesy/The New Era Odyssey

Teacher Somnath Patel, founder principal Maganbhai (MT) Vyas and music head Pinakin Trivedi from Shantiniketan. Pics Courtesy/The New Era Odyssey

New Era fused the finest influences, culling its philosophy from Tagore’s tenets, Gandhi’s secular nationalism, Besant’s reformist ideals and Maria Montessori’s teaching methods. Fortunately, Chandulal’s son Kantibhai and his wife Bhanuben, carried forward their enlightened ancestors’ legacy.

The E-shaped design of the building—flanked by the green hills of Hanging Gardens and historic Gowalia Tank maidan—seemed to mirror the openness with which the institution nurtured thousands of young lives in a completely casual, happy atmosphere.

Counsellor Zareen Jathar and librarian Raden Vanamali (second-third from left) on Sports Day at Gowalia Tank Maidan

Counsellor Zareen Jathar and librarian Raden Vanamali (second-third from left) on Sports Day at Gowalia Tank Maidan

“When the iconic mural on its facade came down, so did the soul of the school,” says Paula Mariwala (batch of 1981). “That collage embodied New Era’s commitment to producing free-thinking global citizens. The prestigious IB organisation of Geneva is amazed this so-called modern pedagogy was practised without pretence or fancy labels in a bilingual Gandhian school decades ago.”

The 10 am clang of its big brass bell reverberating across Gowalia Tank soon echoed an awakening clarion call. “Quit India” cries rang loud from that maidan (hence August Kranti Maidan), a turning point in the Independence struggle. In its wake rose local acts of defiance. Revolutionaries Usha Mehta and Rohit Dave ran a clandestine radio station from the school.

Principal KC Vyas with Jayaprakash Narayan

Raden Vanamali (1955) belonged to the Bohra family of Sirajudin Vasi, steadfast to azadi. Her paternal grandmother swapped cloaking for khaddar which she wore proudly in agitation processions. And her grandfather had marched with the Mahatma to Dandi after the salt satyagrahis rested awhile at their bungalow.

Vanamali’s parents enrolled her in New Era against the joint family’s insistence on English-medium schools. “That decision paid rich dividend. Exposure to the Gujarati language grounded my roots. Parsi teachers fuelled an enjoyment of English literature. Even students from business backgrounds came without the baggage of a flashy lifestyle.”

The school librarian in subsequent years (1967-97), Vanamali says, “Retrieving information took much more time then, today a touch opens windows. Our graded fiction was select and varied. Samajik romances by Ramanlal Desai were as popular as KM Munshi’s nationalistic works.”

Explaining the fascination for discovering traditional and contemporary authors, Paula Mariwala observes, “We take pride in reciting Kalapi and Meghani as well as Keats and Wordsworth, reading Munshi and Dhoomketu along with Ayn Rand and Somerset Maugham.”

A commendable number of firsts wove inextricably within the school’s socio-cultural fabric. Accepted as an associated school by UNESCO in 1957, New Era was listed among Asia’s best. The following year MT Vyas became the country’s inaugural recipient of the Padma Shri for distinguished services in education.

From the trauma of World War II emerged efforts to propagate universal brotherhood among disparate people. Kantibhai Vyas conceived Samanvay. Partnering similarly sensitised schools with the “We are one” motto, this programme catapulted from regional journeys in Vadodara to student camps in Scotland.

“Unity—the spirit of Samanvay—got firmly imprinted. To think of any Indian as less than other Indians was anathema,” says journalist Salil Tripathi (1977). “Kantibhai often reminded us, we were Maharashtrians who spoke Gujarati. The subtle distinction reinforced that we didn’t live in an island of Gujaratiness. Sarva Dharma Prathna on Fridays saw a largely Hindu and Jain school chant prayers of every community.”

The evening after the Emergency was clamped in June 1975, Tripathi and his friends walked home shouting, Liberty Equality Fraternity. “We must’ve looked foolish to many and a Parsi uncle told us to be careful. But teachers had already corrupted our minds, talking about the French Revolution.”

It was about thriving without unnecessary pressure on the academic front. Shifting from the usual system of marks to grades, no exams were set before Std 8. To eliminate rote learning, Kantibhai introduced Open Book exams in the ’60s. Surprise tests reduced the preparation anxiety and an honour code trusted students enough to have no invigilators supervise halls for crucial Std 10 prelims.

“Ours was a laboratory of educational experiments,” declares social studies and maths teacher Dinesh Buch. “New Era was the first to follow Montessori concepts and modern maths. We pioneered adopting a combined approach to social studies, disregarding geography-history-civics as separate subjects. Field excursions and picnics were intentionally conducted in the monsoon, unlike most schools.” Kids complaining of the load of protective rainwear parents provided for outings were delighted to hear Kantibhai reassure, “No harm carrying, who’s compelling you to wear it?”

Mountaineer Harish Kapadia (1962) attributes his love for adventure amid nature to those trips, his passion for history to Daulatbhai Desai. “Our teachers authentically moulded interests. They handled mischief, yet inculcated discipline. Protest was healthy. Caught chatting in class about cricket scores, I could argue reasonably.”

High on anti-Raj fervour, the school substituted the classic Englishman’s game—eccentrically with an American one. “Dismissing cricket as a five-day wasteful craze India couldn’t afford, Kantibhai suggested baseball bat replacements,” says Tripathi. “My mum agreed cricket was addictive jugaar the Brits kept us backward with. Watching Gavaskar on TV, my brothers and I shooshed her.”

In time the sports scene changed in the “simple, democratic, secular school consciously practising gender equality” as Nandita Jhaveri (1972; vice-principal 1994-2005) describes. Her mother served as able wicketkeeper for the ace girls’ cricket team.

Mellifluous morning assemblies resounded with the Rabindra sangeet of Pinakin Trivedi from Shantiniketan, who composed the school anthem, and shastriya sangeet by Prabhakar Joglekar. Luminaries addressing assembly included activist Ravishankar Maharaj, patriot poet Sarojini Naidu, musician Zakir Hussain and danseuse Rukmini Devi Arundale, besides renowned authors and singers.

Of the unique intellectual stimulation and emotional nourishment of formative years here, Ami Kantawala (1988), Adjunct Associate Professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, says, “New Era instilled the principles of cultural assimilation and inclusivity. Art was integrated in every subject. That sparked our curiosity, encouraging deep thinking while making connections across different areas. Creativity rested at the centre of collaborative projects allowing students to truly make the classroom a profound place for possibilities.”

Participating in art events at Mani Bhavan on January 30, Paula Mariwala recollects, “Other schools called them competitions. Our art teacher, Dineshbhai Shah, did not believe in competition in creative processes. He refused to send us. It had to be an ‘art festival’ or ‘event to celebrate Gandhi’. New Era taught us advocacy, to be outliers. In a society obsessed with perfectly accented English and ranks in public examinations, this school in the heart of South Mumbai did not benchmark success against such parameters.”

Her views resonate with a shining roster of alumni, among them art scholar Devangana Desai, the Jhaveri sisters of Manipuri dance fame, figurative painter Ila Pal, musician Vanraj Bhatia, broadcast hosts Hamid and Ameen Sayani, actors Shammi Kapoor and Satish Shah, stockbroker Hemendra Kothari, Nykaa founder-CEO Falguni Nayar and corporate lawyer Bijesh Thakker. There were also unbroken lineages, like the loyalist Mariwalas. Patriarch Jaisinh Mariwala (1949) asserts, “Always a Mariwala in New Era, about 60 of us passed from 1932 to 1984”.

Writer Aban Mukherji (1969) remembers her parents, Dr Kaikhushru and Pareen Lalkaka, being repeatedly questioned—Why New Era?—by Parsi relatives perplexed they consigned their daughter to a predominantly Gujarati school. “We really ‘gained in translation’,” she shared in an article for Parsiana, tellingly titled End of an Era, once the school shut in 2018 owing to a corporate takeover. “I read Jules Verne, Victor Hugo and Leo Tolstoy initially in Gujarati, next in abridged form English and finally unabridged versions. We devoured Bengali novels and wept copiously over Sarat Chandra’s tragic tales.”

Pulin Bihari Dutt from Shantiniketan first headed the art department, urging unbridled creative expression. When Mukherji schooled, Dinesh Shah had taken over—“Our drawings burst beyond boundaries of large sheets of paper, meandering on the floor. No restraining hand stopped us.”

As outspoken, the trenchant bimonthly magazine, Pratyancha, permitted criticism and debate on any issue students wanted

to discuss.

Years since stepping into the premises, generations of alumni and faculty members confess they never pass Hughes Road without a wistful sigh. Each inwardly exulting, Dhanya New Era!

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!