Hussain, termed the mastermind of Delhi riots, used to host over 1,000 guests every Holi and Diwali. Would a communal person do that, asks his son, standing in his father’s office—now a museum of innocence

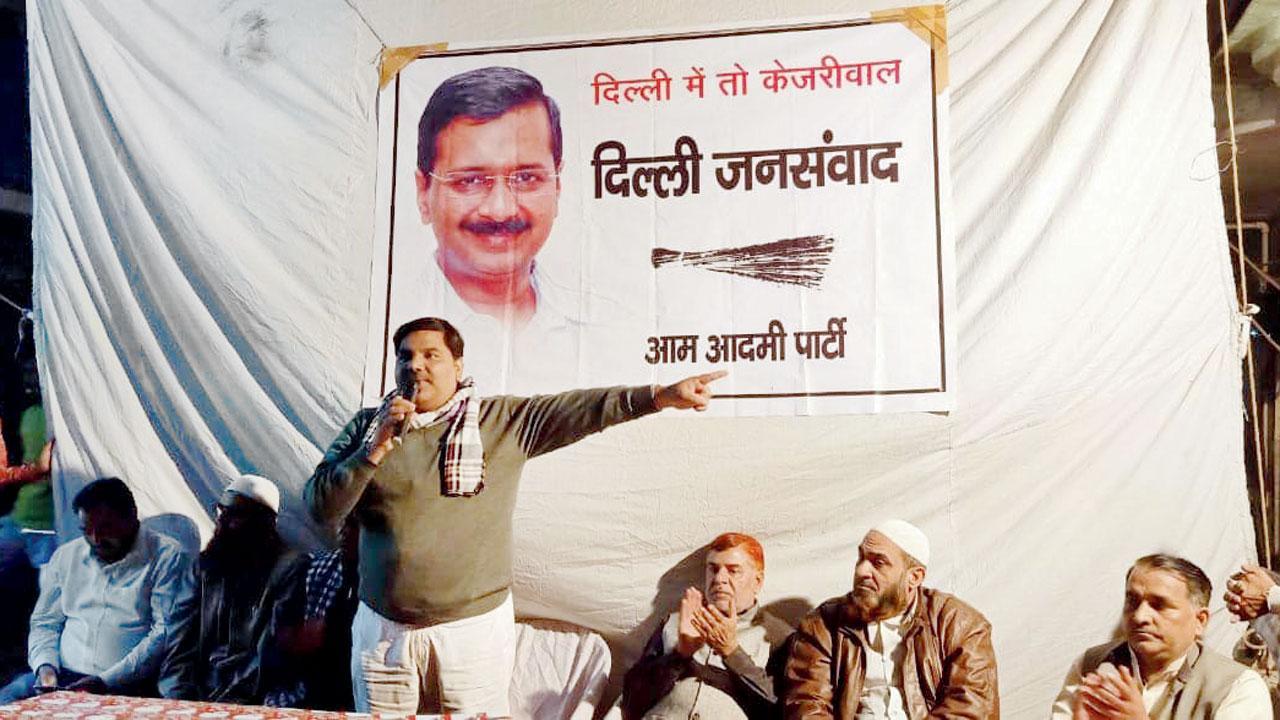

Tahir Hussain, former councillor, addresses a gathering of AAP supporters. The party, however, suspended his primary membership soon after the allegation, reinforcing the impression of his alleged culpability. Pic/Facbook

Former Aam Aadmi Party councillor Tahir Hussain is embedded in popular consciousness as the man who masterminded the February 2020 riots in Northeast Delhi that occurred on the day then US President Donald Trump landed in India. The motive behind his villainy, it was said, was to exploit Trump’s visit to rivet the world’s attention on the protests against the discriminatory Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, leading to the clamour that such a man should not be forgiven. Sure enough, Delhi Police booked Tahir under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and packed him off to jail, where he languishes still.

Former Aam Aadmi Party councillor Tahir Hussain is embedded in popular consciousness as the man who masterminded the February 2020 riots in Northeast Delhi that occurred on the day then US President Donald Trump landed in India. The motive behind his villainy, it was said, was to exploit Trump’s visit to rivet the world’s attention on the protests against the discriminatory Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, leading to the clamour that such a man should not be forgiven. Sure enough, Delhi Police booked Tahir under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and packed him off to jail, where he languishes still.

ADVERTISEMENT

In many ways, though, Tahir is arguably the biggest victim of the Delhi riots. In a five-part series on the Delhi riots for The Wire, N D Jayaprakash showed Tahir’s four-storey building at Khajuri Khas, one of the sites of the violence, came under attack on February 24. He made 12 calls to the police. They belatedly arrived around 8 pm at the building, which, spread over 1,100 square yards, housed his residence, his company’s office and a furniture production unit. They searched the sprawling construction to ensure intruders were not hiding there. Tahir and his family shifted out, and handed over the keys of the building to Delhi Police.

Yet, on February 27, a TV channel beamed a spliced-up video showing men on Tahir’s terrace had commandeered a veritable dump of stones and bottles. A narrative was spawned that Tahir had provided the spark that lit the fire in Northeast Delhi. Given that Delhi Police possessed the keys to Tahir’s building, did it not follow that the bottles and stones were planted, Jayaprakash asked.

The TV narrative triggered a chain of consequences for Tahir. Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal suspended Tahir from AAP’s primary membership, reinforcing the impression of his alleged culpability.

Twelve cases were filed against him, including one by the Enforcement Directorate. Is it just a coincidence, or a testament to the power of the media narrative, that Tahir has not been granted bail even in those cases in which the co-accused have been given relief?

Last week, I went to Tahir’s building, with his brother-in-law Usman and his elder son Shariq, who awaits his BCom results. A couple of employees loitered around. Rows of workstations lay vacant. The doors to the director’s office and the conference room were shut. The silence and darkness imparted a desolate feel to the place. Before the riots, Usman said, the place hummed with over 200 employees.

The company was in the retail fixture business, which entailed making showrooms countrywide for a slew of multinational companies. In 2019-2020, Tahir paid R5 lakh as income tax, a spectacular achievement for one who entered business as a 14-year-old.

The infamy maliciously scripted for Tahir ruined his business, as did the Enforcement Directorate investigations probing the sources of his funding. His personal and company’s accounts were frozen.

Employees left. MNCs stopped replying to Usman’s mails, and their executives refused to meet him even when he went to their offices. Tahir was now a pariah, for scripting the riots that brought India into disrepute. His MNC clients held back dues running into lakhs, apprehensive the ED would question them about the payments made. The problem of liquidity became so acute that the family had a tough time raising money for paying the fees of Tahir’s two children studying in an elite Delhi school—and for covering legal expenses.

Tahir’s wife Sama joined us in our conversation. The family no longer lives in the building, which was reopened six months ago. Who would want to live in the building having an eerie feel about it, where happy memories died overnight? They live with Tahir’s parents, in a joint family household, smothering wishes they could, before 2020, fulfil without a thought. “My second son, in Standard XII, no longer orders food from outside; my daughter, in Standard VIII, wakes up at odd hours of night, asking for her father. He has lost so much weight in tension,” Sama said, pointing to Shariq.

Tahir seems to have slipped into depression. During the five-minute call permitted daily, he harps on being accused of a crime he did not commit, a crime he says he is incapable of even conceiving. Perhaps this is his way of assuring himself that he is not to blame for the family’s plight. “Dad never had communal sentiments,” Shariq said. If he were communal-minded, would he have resided on the Hindu side of the road that separates it from Muslim quarters at Khajuri Khas? Would 60 per cent of his employees have been Hindu? Would he have hosted over 1,000 guests every Holi and Diwali?

Anger simmers inside Shariq, anger he cannot vent; anger that is futile. He and Usman led me to the room where Tahir would sit until February 2020, and switched on the lights, revealing a cosy, plush office, dusted up and neat, as if frozen in time. What’s his anger about, I asked Shariq. “It is about how a victim can be turned into a villain,” he said. I felt I was standing in the “museum of innocence.”

The writer is a senior journalist.

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!