As Bombay gasps for life, we revisit small street vendors - scarred, scared and struggling to survive

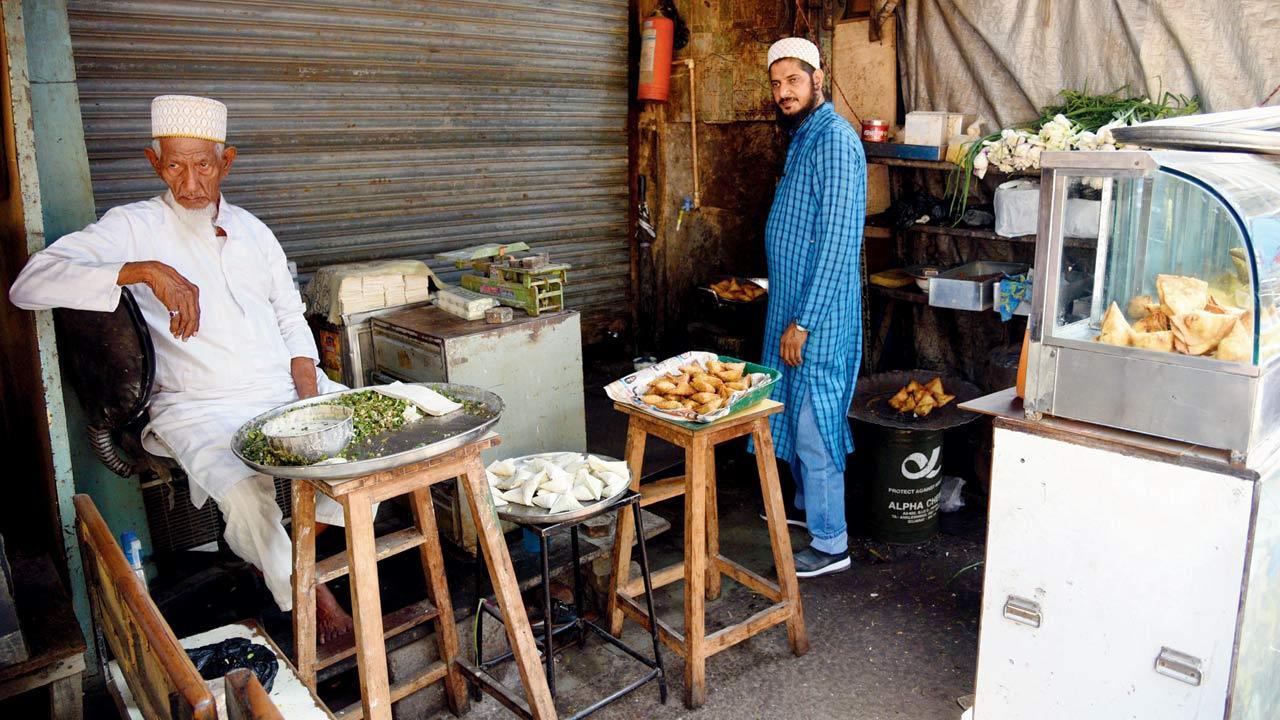

Diamond Samosawala’s Burhanuddin (right) with his father Hakimuddin at their earlier stall in Bhendi Bazaar. File pic

You are from Navsari? Wah, that is nice,” pronounces Masood Shaikh. He is the brother of the late Mohmmad Anis Shaikh. Their atmospheric 1930-established shop, Dada Nanji Kamarsi Surmawala—its wall-mounted capital alphabet eye charts sharing space with well-thumbed Thames & Hudson tomes—featured two years ago in the Dongri column on these pages.

ADVERTISEMENT

Last year, the city lost one of its oldest surma sellers and liveliest raconteurs. Like his surviving sibling, Mohmmad Bhai had been enthused to figure we had antecedents in a common Gujarat town. A predictably patriarchal line of questioning—“Marfatia is an Ahmedabadi-type surname. Where is your father’s family from in Gujarat?”—revealed my ancestors were priests, his poets.

Vinod Jadhav waits to sell sandwiches again outside St Xavier's College. Pic courtesy/Daniel Marsh

Gulam Nabi Taufiq of Navsari, who instructed his son to concoct cooling surma from germ-ridding antimony from Jordan, also composed scintillating verse in Gujarati. An accomplishment winning him admirers, like the owners of Mercantile Bank and Mumbai Samachar, when he arrived here in 1920.

“Our father taught us to appreciate all things artistic and make a living with respect for tradition,” says Masood. “COVID thins customers for our soothing surma made from ayurvedic extracts. Distancing has brought changes. Instead of service, we just sell health products.” I nod, recalling how his brother rimmed tired eyelids with deft swathes of cool surma.

With a single, simple sales skill they have ever practised, most hawkers’ earnings depend entirely on passersby. Felled by the debilitating uncertain demand for their wares today, they are the invisibles of Bombay. A city fighting for life itself shunts its little people off the streets.

The late Mohmmad Anis in his Dongri ancestral shop, Dada Nanji Kamarsi Surmawala. File pic

“We try being patient, lying to ourselves that this situation cannot last long. I suppose thousands have it worse than me,” Vinod Jadhav attempts reasoning. The worried sandwich seller pools in paltry sums to boost a joint family income in his Chira Bazaar house. He shut Jai Ganesh stall outside Gate 2 of St Xavier’s College from March 2020 to this January, closing again from April 4. “In spite of no business, I turn up occasionally to ensure others won’t pounce on the spot. We don’t dare fall sick. Imagine medical bills adding to loans,” he frets, his usual cheery tone replaced by ragged, shallow-short puffs of anxiety.

Operating in the shadow of an icon — FW Stevens’ stunning Venetian Gothic-meets-Indo Saracenic BMC edifice—Jadhav has been a hit with legions of campus fans and civic officials. Toasting easily over two dozen sandwich varieties, he incredibly remembers the personal preference of hundreds of regulars. The instant he sighted my son approach from the college quadrangle, Jadhav would wave and swiftly slice potatoes for his special order: grilled aloo-cheese topped with a yellow sheet of sev melted by hot butter beneath. “My family vaccinated at Cama Hospital. We do everything correct, but are finished,” he despairs. I wince at the irony of “Urbs Prima in Indis” inscribed with the protective winged angel of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation headquarters overlooking his stove.

Peaking from the machinations of partisan politics, the pandemic axes countless roadside trades daily. Stuck with paperback stacks on the footpath in front of Beauty Art laundry at Stadium House on Veer Nariman Road, Janardan Pandey angrily says, “Following government guidelines leave us aam janta in the lurch.” Churchgate Station commuters and generations of collegians have stopped to browse or buy his titles since 1976. “Kaisi kharaab hawa chal rahi hain, kya haalat bana di sabki. Gasping for oxygen, breathless people die literally like fish out of water. I feel afraid to travel from Goregaon, risking virus infection in crowded trains. Money needs to be sent to jobless brothers and uncles in Varanasi. No public, no officegoers, na koi Marine Drive ghoomne wale nikalte, so I come on alternate days.”

Byculla florist Dilip Salunke wants to soon oblige Parsi customers with torans on significant days. File pic

On an afternoon when this bare patch of pavement misses him, a stark empty street allows a clearer view of the building behind, named for the country’s first permanent sports field. Negotiations for Brabourne Stadium, opened in December 1937, involved Lord Brabourne and Anthony Stanislaus de Mello, a BCCI founder. De Mello apparently queried, “Your Excellency, what would you prefer to accept from sportsmen—money for your government or immortality for yourself?” The Governor choosing the latter, the Cricket Club of India was assigned 90,000 reclaimed square yards. Architects Gregson, Batley and King designed the project, while Shapoorji Pallonji & Co. was contracted to erect the massive ground.

Pandey’s plight prompts me to check on Mahavir Singh, usually found outside the medieval Italian-styled Central Telegraph Office at Fountain, which was the General Post Office from 1870 to 1913. He answers the phone in Darbhanga where he is nursing a sick wife. “Corona nahi, Bhagwan ki krupa se,” he says, voice thick with relief quickly falling flat. “What to do in Bombay even if this emergency didn’t bring me home—wahaan toh buri tarah se fas jaate. Bahut dhikkat hoti, sweating in a tiny chawl room. My income is drying and kheti-baadi will destroy in untimely rain. Life mein aisa tension kabhi dekha nahi. I only pray migrant friends returning to Bihar suffer less than they did last year.”

Stocking vintage 1945 to 1965 newspaper issues and rare magazine editions, Singh has seen better days, including Lonely Planet mention of his esoteric collection. Earlier, located behind the University in the 1990s, he enjoyed interacting with writers like Ramchandra Guha and Pritish Nandy.

Janardan Pandey amid his books on the Stadium House pavement, holding up Michelle Obama’s autobiography

Other street-to-store stories present happier updates. Hawking samosa pattis for seven decades, Burhanuddin Bhai at Diamond Samosawala reports no more than a couple of relocations. I interviewed him—and his father Hakimuddin, proud to have supplied their famed strips to the Taj too—when the Bhendi Bazaar cluster rehabilitation scheme was underway three years ago. We met at their corner stall on Saifee Jubilee Street, facing Noor Sweets which marks a century. From there he was shifted to Pydhonie and currently occupies a larger set-up at Nagpada near Rasul Masjid.

“Destiny ni dua thi dukaan chaalu chheh,” says Burhanuddin whose range extends to shami rolls, chicken cutlets, spiced kababs and kachoris. Wherever he goes, loyal customers still bring home-mixed mince and onion stuffing, which he folds within neat patti strips, forming a plump samosa triangle that fries to crunchy perfection.

Buffeted between what he declares a “kabhi khushi kabhi gham” situation, phool wala Dilip Salunke admits he is fatigued, but not defeated by ebbing workdays. That Karan Johar-popularised catchphrase is all the Hindi he utters when we talk. And not a word in his mother tongue. Positioned opposite Byculla’s Rustom Baug and neighbouring Jer Baug, the Marathi manoos spouts Gujarati with startling fluency.

Stringing fresh buds for toran garlands as his grandfather Govind did at Shri Sainath Flower Shop from 1930, Salunke says, “We grew with Parsi patronage. Though Chiplun is my native place, I consider myself a staunch Mumbaikar. After both lockdowns no one knows where they belong. The situation should improve before a demand for my flowers starts with the Muktad days,” he says, referring to the fortnight of the Shahenshahi Zoroastrian calendar preceding New Year, honouring the departed. Khodai badhaa neh raakhnaar chheh—God protects everyone.”

In a shattering dystopian scenario where governance is kaput, prayers alone provide some succour. The surreally static city forces auto and taxi drivers to await food rations from private donors. Hopes dim, debts pile, desperation mounts with plans more scuppered than spared.

I think of Shibani Bai hawking chana, chikki and laddoos in a dusty cranny of Mahim’s Mori Road, to bring up three children. Of Atmaram Dubey from Jaunpur, UP, who has sold paan and boiled sweets for 40 years under a peepul tree in Wadala. Of the anda-pav and noodle wala at Five Gardens, near whom Lakhan Golawala introduced 1960s Bombay to the tart kaala khatta flavour it instantly loved.

Where must she be, the leather worker at Agripada’s Bait ki Chawl, who hated a harassing factory boss, but needed to afford her children’s fees for Madanpura’s new English school. Or the vendor of handkerchiefs and ballpens below 1901-opened Empire Hotel on DN Road, taking home to Mulund the once-a-month McDonald’s burger treat for his daughter.

Then there was Salf Bibi, feistily in her 80s, switching three buses from Juhu Koliwada to reach her gems shop off Mohammed Ali Road. Born in Bandar Abbas in Iran, she inherited the counter from her father-in-law Usman Zaveri. “We match stones to astral fortunes when people suffer low dhandha paani phases,” she said three Aprils ago, brown eyes glinting to her nose-ring.

Flickers of warmth somewhat keep the faith. Catching up with Yvonne D’Souza in Borivli, I learn her family continues to cook and distribute free nutritious meals for growing numbers of lonely elders. Rising to the crisis, she adds dabbas for those stranded quarantining. Besides caring for a handful of senior citizens in the small flat I have visited. There, a toothy 95-year-old had burst into peppy Portuguese songs and lisped blessings for my kids.

Body blows batter Bombay bad. Can its soul keep straining to stay strong?

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. Reach her at meher.marfatia

@mid-day.com/www.mehermarfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!