What if everybody’s a celebrity, including stars online, are they stars still?

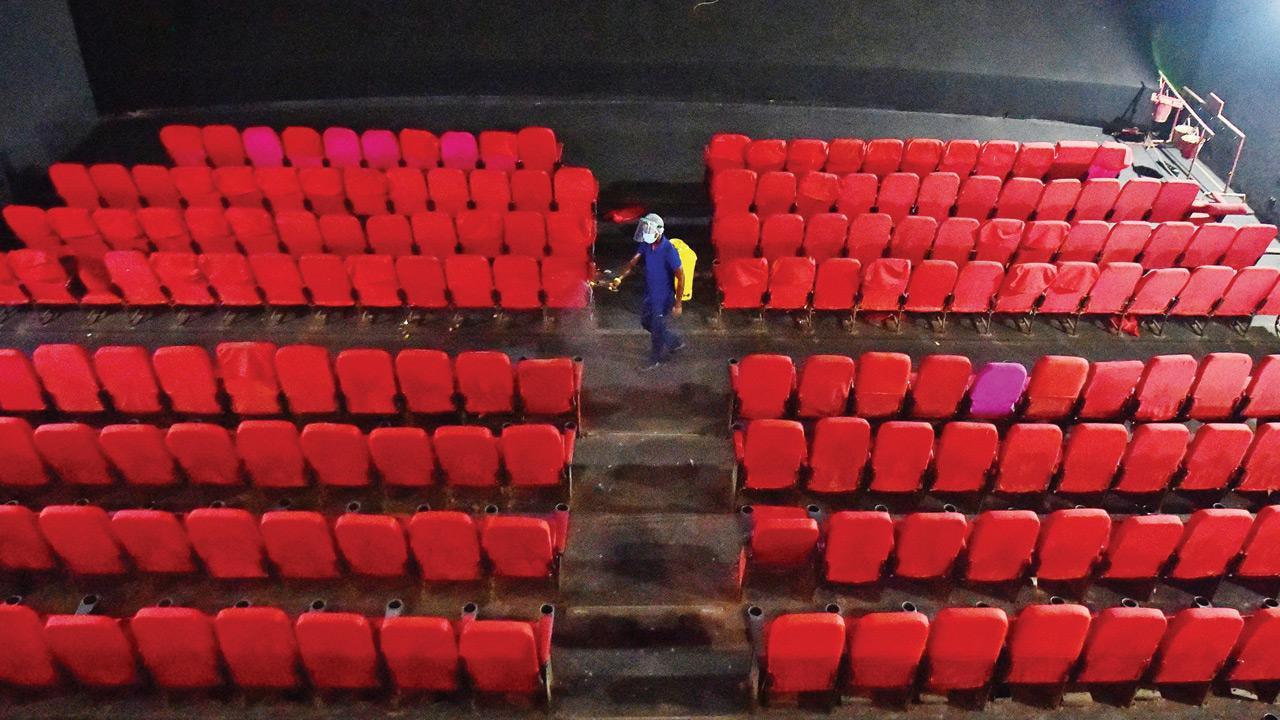

Entertainment has moved away from theatres in the past year and a half due to Covid

Kabir Bedi, among the most introspective actors I’ve spoken to—after over 50 years of being in cinema/entertainment—tells me why he feels his colleagues are the most insecure lot you’ll know. Firstly, the fame they achieve as a result of their profession is ephemeral by nature. It fades, necessarily.

ADVERTISEMENT

Two, they deal in storytelling, an emotional product, with nothing quite tangible to it—for you to tell how it’ll be received, or discarded. Sure, those stories, indeed even fantasies, add something to people’s lives. But if they don’t, they’re useless.

Also I guess it doesn’t help that one is rapidly deemed God by masses, when it comes to popular cinema—given the size of actors as they appear on a giant screen, reducing audiences to bhakts looking up. The lead actor is called star! The movie is where the line at a cinema is—and it starts from the star’s poster/hoarding at the door.

Now you may think (rightly) that these traditional stars receive adulation disproportionate to their contribution/talent/skill. But the fact is, it’s this star system, as it were, that’s defined mainstream for at least seven decades in movies—enticing public towards a story being told, with the star as a gravitating medium.

For the longest, cinemas, therefore stars, had no competition at all—by the ’80s, it was the haystack rotating at appointed morning, afternoon, evening time-slots, turning into the Doordarshan logo, for a couple of hours of entertainment to follow.

The only real competition came in the same decade though, when video cassette players became affordable to middle and upper classes, and they pretty much quit going to cinemas as regularly.

Some of the brightest filmmakers moved to television. Lower income groups became chief patron of entertainment in theatres that were cheaply priced, but quite stinky too!

What does it take to run a cinema of, say, 200 to a 1,000-plus seats? That many people through the day, on most days of the year, to keep it packed and running! The multiplex, at the turn of the century—with audis for varying audience sizes—rendered cinemas, now called ‘single-screens’, economically unviable.

This is also roughly the time movies stopped celebrating silver/golden jubilee (25/50-week) runs. Why would they, once the film is already out on video, or TV? Which of course coincided with private/satellite television in India—soaps and reality shows, music videos and television news.

What kinda stars did long-running stories on TV create? The sorts of Amar Upadhyay in Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi, who’d play Mihir. His exit from the show would send masses in tears. But that would do little for Amar. It could actively work against his career. What else can he play? He is Mihir.

That was the nature of the beast. Something that Kabir Bedi discovered when, like Arun Govil as Lord Ram, he played Italy’s greatest icon Sandokan on national TV in the ’70s. Italy went nuts over him. But what else could he play in Italy thereafter to cash in on that stardom? He was Sandokan for life.

What’s the key difference between cinema and television, or all other screens in fact—cellphone, laptop, tablet…? That you fish out money from your pocket for appointed viewing in a cinema, which in turn directly funds the product—something that’s true for no other media in India.

There is also the extreme, undivided attention inside a dark hall—although of all other screens, I find the cellphone, right before my eyes, and sound from an earphone, as most immersive—way over TV for sure, and after theatre, of course!

Both these aspects define stardom. One, over the hard cash their films draw at the box-office. And the fact that people are interested enough to look absolutely nowhere, but at their giant projection on screen for over a couple of hours, minimum. Winner takes all.

What happens when the same stars’ films directly premiere on a Netflix or Amazon, that you subscribe as a service, but don’t pay for a particular piece of content?

Notwithstanding vast advertising budgets to make the entry seem like an event still—on a levelled playing field, they merge with everyone else on the platform, and a Jaideep Ahlawat (Paatal Lok) is as much a rage as Varun Dhawan (Coolie No 1), if not more. That’s how we’ve consumed content for a year and half during COVID.

Even with theatres reopened, Internet exposure = Marvel’s Shang-Chi > Akshay Kumar’s Bell Bottom. But the cinema star, without the cinema, further loses sheen. As you may have observed during a social/mainstream media campaign to vilify mainstream Bollywood after actor Sushant Singh Rajput’s death, during the pandemic, when theatres were shut.

Likewise, if they land exclusively online, they must commune with everybody else in the life of the Internet—full of YouTube sensations that come/go, and influencers on social media, attracting millions at one go.

Creating circles over circles of massive niches, where you can discover a phenomenon particular to a group every day, who you’d never heard of before. Everybody’s a celebrity. Who then is a star (you actively pay for)? And if there is no star, what then is mainstream? That’s a question quite key to when Bollywood’s audiences return to theatres!

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!