Last of the Vedic texts

Updated On: 13 June, 2021 09:35 AM IST | Mumbai | Devdutt Pattanaik

But thanks to subjects collectively known as Vedanga (limbs of the Veda), we know the words—how to pronounce them (Shiksha), what they mean (Nirukta), the grammar (Vyakarna), the meters (Chhanda) and how they were used in ceremony (Kalpasutra).

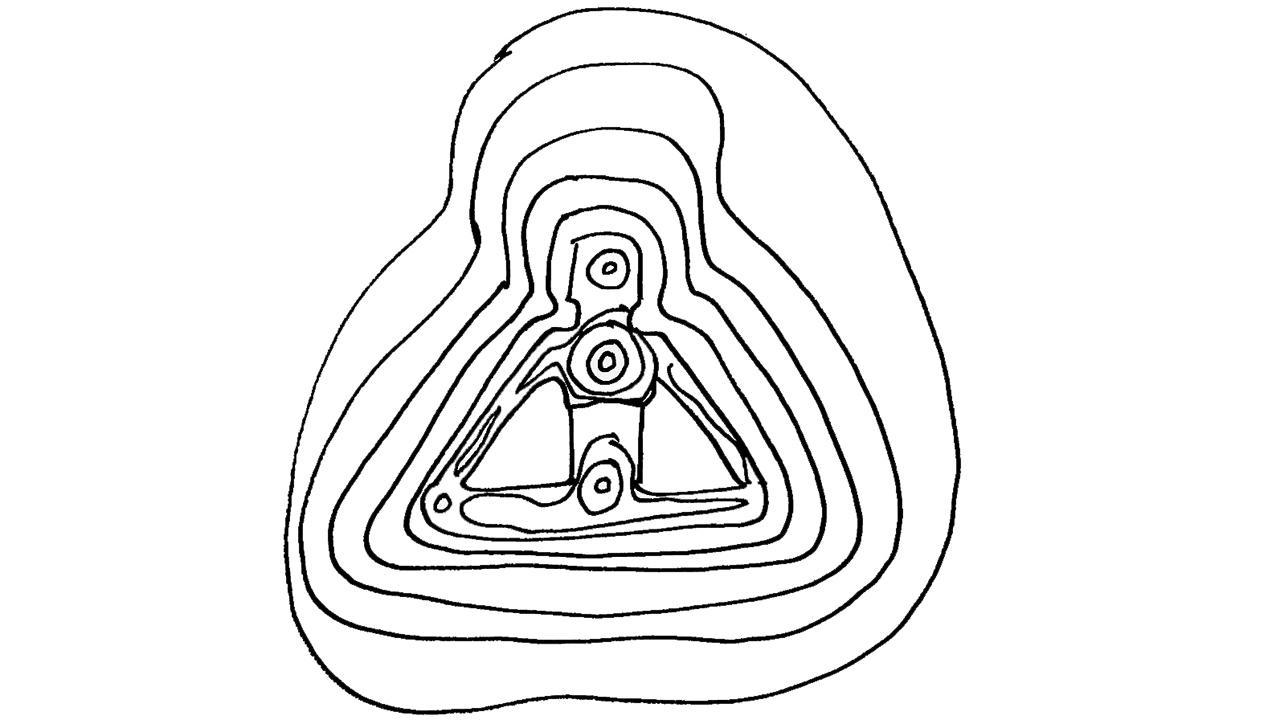

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

In the Mimansa school that became popular 2,000 years ago, the Rig Veda was considered ‘apaurusheya’ (not of human origin) and ‘ekavakya’ (a single sentence), with no breaks between words and no punctuations. Sounds (pada) fused to create words (shabda) which merged with other words (sandhi) which gave rise to verses (richa) which became hymns (sukta) which gave rise to circles of songs (mandalas) which became the entire collection (samhita). But thanks to subjects collectively known as Vedanga (limbs of the Veda), we know the words—how to pronounce them (Shiksha), what they mean (Nirukta), the grammar (Vyakarna), the meters (Chhanda) and how they were used in ceremony (Kalpasutra).

People believed that the composers of the Rig Veda ‘saw’ the mantras, which is why they were called rishis, or the seers. We now know that these were praise hymns, composed over 3,000 years ago, were designed to invoke and invite gods such as Indra to the yagna. Over time 1,028 such hymns were compiled by different families of rishis, which were passed on orally by various brahmin family branches (shaka).