A Pune scholar’s research underlines the vibrant connection between Gujarat’s foremost poet Narsinh Mehta and Maharashtra’s favorite god Vitthal

Narsinh Mehta immortalised in the museum at the poet’s residence in Junagadh; Bathe photographs the memorabilia

![]() Researches are restless souls—they see connections that are unacknowledged in the public discourse; they unearth material that is difficult to locate; they go the extra mile to pursue the project at hand. Just as Pune-based Manisha Bathe, 53, who travelled all the way to the state of Gujarat, while working on her eighth book, Vitthal Namacha Bharat Sanchar: Gujarat.

Researches are restless souls—they see connections that are unacknowledged in the public discourse; they unearth material that is difficult to locate; they go the extra mile to pursue the project at hand. Just as Pune-based Manisha Bathe, 53, who travelled all the way to the state of Gujarat, while working on her eighth book, Vitthal Namacha Bharat Sanchar: Gujarat.

ADVERTISEMENT

Her in-depth exploration of Gujarat’s aadya kavi Narsinh Mehta’s poetry—particularly, in the context of the mentions of Maharashtra’s saint-poets like Saint Namdev—forges a precious link between Maharashtra and Gujarat. It is part of her larger project to locate the influence of Maharashtra’s saint literature and Vitthal worship traditions beyond the Marathi language. After Gujarat, she will embark on Rajasthan’s Vitthal devotion; Punjab is also on the anvil since Saint Namdev lived and meditated in the village of Ghuman in the Hardaspur district before attaining salvation.

Bathe’s work focuses on the published-unpublished and handwritten records of Narsinh Mehta’s literature, which abound in mentions of Pandurang, Pundalik, Vitthalo, Vithalda, Pandharpur, Varkari and Saint Namdev. The Gujarati verse bears direct reference to Mehta’s longing to meet the Lord by doing a vari (pilgrimage on foot). In fact, he had undertaken the vari from Junagadh on several occasions; his poetry imbibes the spiritual observance of the ashadi and kartiki ekadashi. Contemporary scholars of Gujarat, as late as Dr KK Shastri and Umashankar Joshi, have spelled out the impact of Saint Namdev (1270-1350) on Mehta (1414-1481).

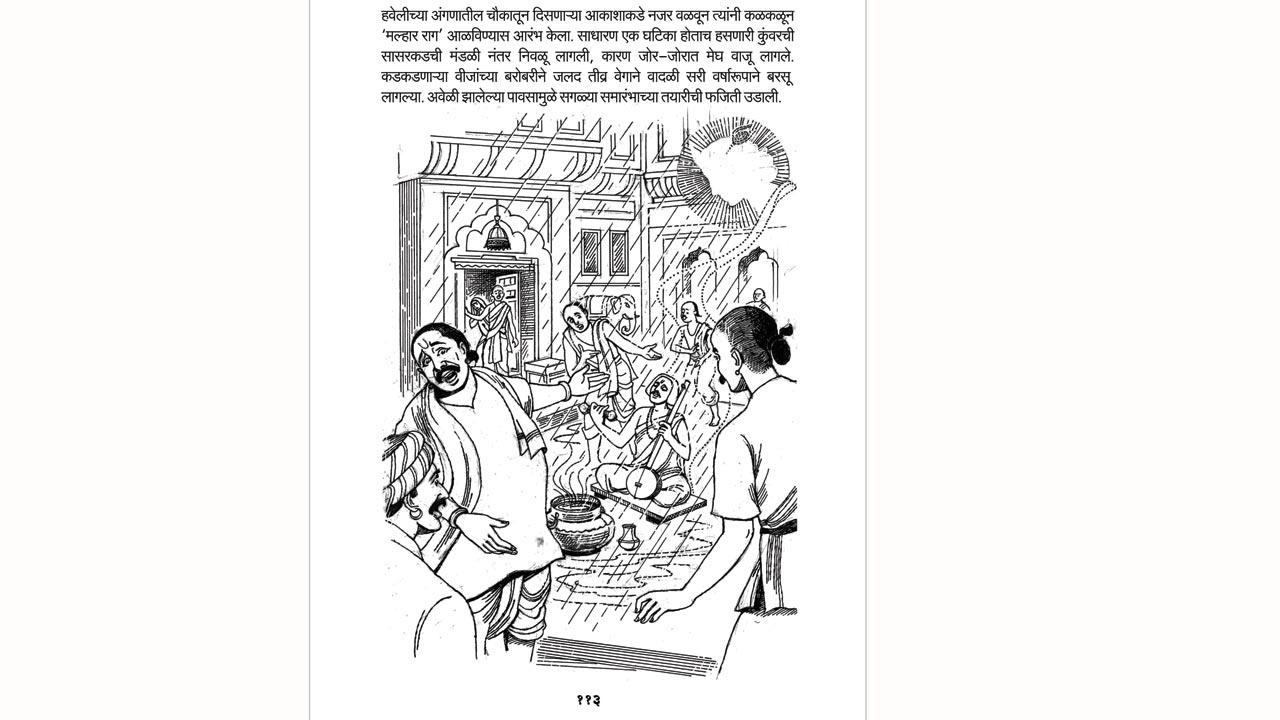

The bilingual book has illustrations by artist Anil Upalekar

The bilingual book has illustrations by artist Anil Upalekar

It is another story that post 1960s, after the formation of both the states, Marathi and Gujarati were not perceived in unison. The bhagini bhasha sentiment evaporated after the 1970s, claims Bathe who sensed regionalism—not just in Gujarat—in the treatment meted out to her research subject.

“Even when I showed the mentions of Shree Vitthal and Pandharpur in Narsi Kavyadohan [published around 1884, edited by Iccharam Desai], the authorities in Junagadh said the lines must have been added [vacche nakhelo che] later. I, therefore, rushed to Baroda to corroborate my claim. That’s when I chanced upon 25 unpublished padas, which contained the precious search words I was seeking.”

As Bathe showed consistency in her pursuit of documents and dates (samvat varsh differently counted in Marathi and Gujarati cultures), she gained the confidence and respect of the daftar holders.

Manisha Bathe

Manisha Bathe

Bathe’s bilingual book traces Mehta’s literary journey across the length and breadth of Gujarat; she interacted with key institutions and people in locales where the poet left his footprints—Mangrol, Somnath, Dwarka, Baroda and Junagadh. Her research doesn’t stop at that—it extends to 21 other poets (avowed disciples of Mehta), spanning 500 years up to Narmadashankar Lalshankar Dave alias Narmad (1883-86), who refer to Vari, Vitthal and Pandharpur.

The book elucidates-annotates Mehta’s Gujarati verse with Marathi translation; it also has a critique of the rare excerpted texts. There are some direct prayers: “Veelam na karsho Vitthala re/ Am gher aavo aaj” (Don’t be late Lord Vitthal, Visit my home today); the poet identifies Vitthal as the “shyam sundar natvar” who is playing the Venu; Rukmini is always by his side; the Lord is also seen as a commoner “Vitthalo vanma gaayu chaare”—he takes the cows for forest grazing.

Mehta holds Saint Namdev’s devotion and surrender in high esteem (Dhruvtara chhe uparma ta shoo, Namdevni balihari) even above the North Star. For Mehta, Namdev was the supreme Vaishnav ideal. Much like Namdev ends his abhangs with Nama Mhane, Mehta takes to “Bhane Narsaiyyo” or “Narsaiyyacha” signature style.

Bathe presents a two-channel connect. She quotes Marathi saints who have mentioned Mehta. For instance, while recalling the magic infused by Lord Vitthal in various saints’ lives, Saint Tukaram mentions Namdev, Narsinh Mehta, Kabirdas, Gora Kumbhar and Mirabai in the same breath. “Hundi tya Mahetychi Ange Bhare” which, in today’s parlance means God encashes Mehta’s cheque. Also, both saints—Niloba and Janabai—mention Mehta as an archetypal devotee of Vitthal.

“The composite body of these bards indicates the significance of Vitthal bhakti in Gujarat or rather beyond Maharashtra, a fact not acknowledged in recent years. One wonders why such a beautiful aspect, which binds Maharashtra and Gujarat, is underplayed by the Vaishnav sect followers these days, and also by the political leaders who otherwise make a big deal of Hindu unity and Bhagavad dharm,” says Bathe, whose life’s mission is to demonstrate the pan-Indian appeal of the Varkari tradition.

The scholar’s tryst with Mehta dates back to her post graduation in Gujarati (2013). Gujarati is among the seven Indian languages that Bathe studied formally, though she has a working knowledge of 11. A great believer in the healing power of languages, she built bridges all over Gujarat because of her articulation. “Those who initially questioned my credentials as an independent researcher of the Narsinh Mehta canon, later helped me to gather archival material, thanks to my spoken Gujarati,” the scholar shares.

Bathe relied on diverse institutions for archival resources and manuscripts —Oriental Institute (Vadodara), Bhaktakavi Narsinh Mehta University (Junagadh), Shri Vallabhacharya Sampradaya Baithak Mandir (Dwarka and Pune) among others. She interacted with Mehta’s 22nd descendants, at the same time gained access to daftars of temple trusts, sourcing rarer handwritten texts. For earlier research on the influence of Saint Ramdas’ literature, she visited similar daftars of handwritten records in Karnataka (Basavkalyani, Aland, Apachand) and Andhra Pradesh (Osmania University and Marathi Sahitya Parishad in Hyderabad), which will come in handy for her later pan-Indian documentation of Varkari culture.

Interestingly, the manuscripts in Gujarati, which Bathe pored over, are not a homolithic entity. The content lies in various dialects—Sorathi, Apabransh Gira, Marugurjar, Gurjari, Maru. The poetic compositions in these dialects (of Mehta and followers) also differ, with songs, bhajans, garba, and garbi. “I see regional language streams as powerful expressions; in fact the praman bhasha often lacks their colour. I am blessed to have the agency to decipher the gold in these lingos. Unfortunately, this gold will turn to dust with the passage of time, unless we take to better preservation practices,” she says.

According to Bathe, tonnes of manuscripts deserve to be treasured and deeply scrutinised. “I have touched only the tip of the iceberg,” says the self-driven scholar, whose books are published by the Samarth Media Centre, that her sister Asha Bathe runs in Pune. The family enterprise, which is about to turn 25, and is situated in Pune’s iconic Narayan Peth, has won many awards in the publishing industry.

Despite the support of a publishing house, Bathe feels lost in terms of research tools. She has to often get endorsements-validation from government bodies for gaining access to material and institutions. She wishes for inter-state university linkages, which help unaffiliated researchers. “Whether in Gujarat or elsewhere, the academia treats book projects with scepticism. I have to often explain my personal reasons for studying the Varkari sect in and out of Maharashtra,” she says. Bathe was raised by an impoverished widowed mother in Satara, which comes under the ideological impact of Sajjangadh, the headquarters of Ramdasi Sampradaya. She was drawn to saint literature quite early on, which later became a passion when she transitioned to Pune for college-university education. For her, one publication signals research for the other, which is why she has given an open-ended title to the new series, Vitthal Namacha Bharat Sanchar. Incredible India she calls it!

Before Bathe takes on her tours of Rajasthan, she has another task at hand. She is giving finishing touches to a book paying homage to the prodigious sports literature (1936-50) produced by a Baroda-based couple who launched a magazine on Indian physical education and Akhada culture. “It’s my offshoot research book whose protagonists will be under wraps until publication. As I was sourcing manuscripts of Mehta’s works, I discovered the Gujarati, English and Marathi texts written by the couple on various sports from the Vedic times to the 19th century.” She was surprised to locate the Maharashtrian couple’s honourable mentions in Gujarat’s records too. When she chanced upon the unique pair, she thanked Mehta —the years of magajmari in Gujarat paid off!

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!