As a sequel to a recent column, a family romance that celebrates the magic of music in fusing an uncommon bond

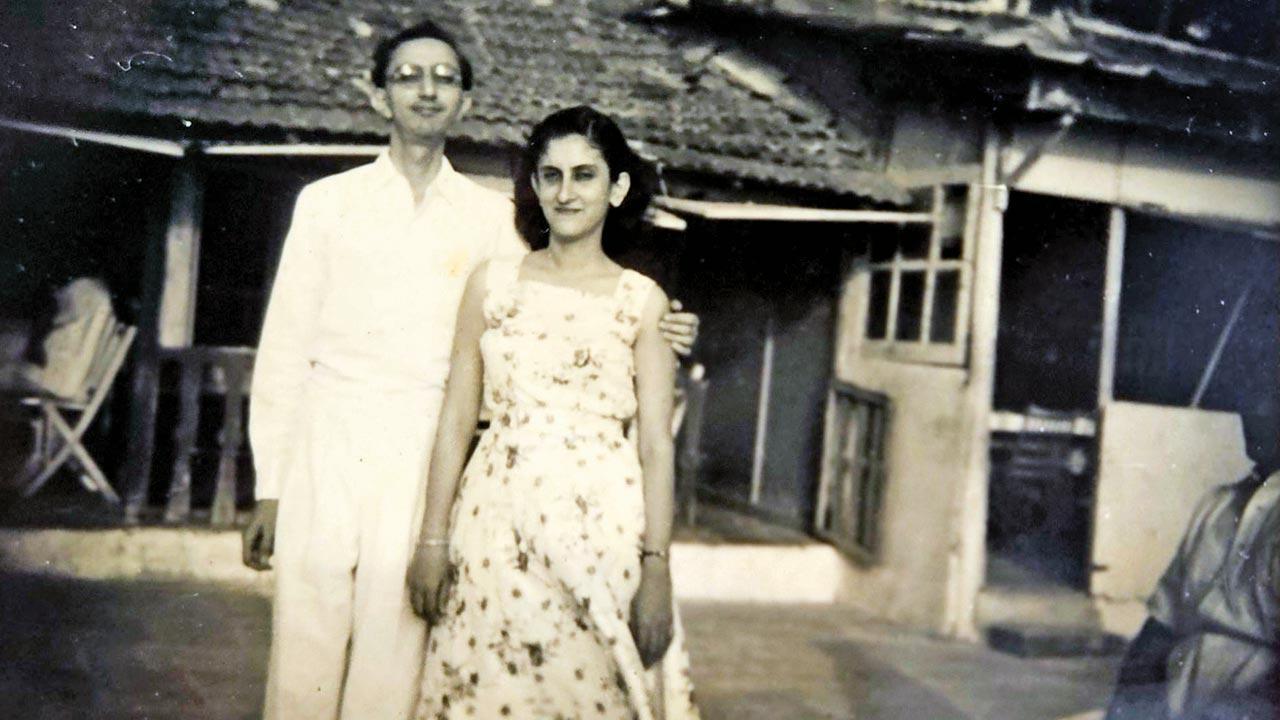

Homi and Homai Dastoor in Navsari in 1959, the year of their marriage

ADVERTISEMENT

I thought about it quite a bit. A personal retelling of my parents’ romance is not for general sharing in the public space of these pages. But a whole month after the “Very, very Valentine” column, featuring the love stories of mid-20th century couples bound by cultural threads, readers still plead for an account of my parents’ life journey.

Its different phases spanned interesting city neighbourhoods. My brother Phiroze and I were Bandra-bred but Dadar-born, to Homai Joshi and Homi Dastoor. They met at Perviz Hall, the Dadar Parsi Colony’s one-time social hub. Dad wooed and won Mum with a delightful lecture series he delivered on Western classical music, demystifying the genre that intimidates many. I imagine how hundreds of young couples must have dated at what is now a centre selling sweet bakes like bhakra and pori, and taking orders to stitch sadras, the sacred muslin vests Parsis wear following their Navjote initiation to the faith.

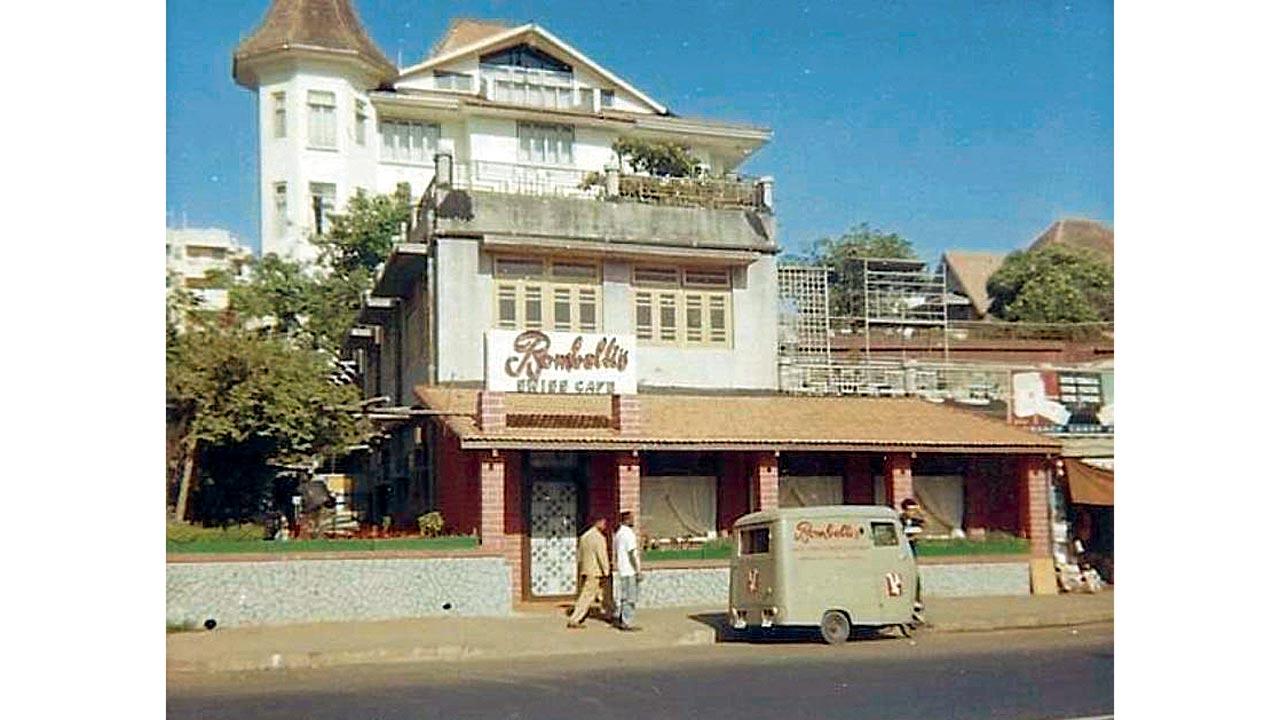

Bombelli’s at Breach Candy, where they celebrated post-proposal. Pic Courtesy/Anita Bombelli

Bombelli’s at Breach Candy, where they celebrated post-proposal. Pic Courtesy/Anita Bombelli

Our father proposed patiently every two years, understanding that his beloved’s hesitation before taking the plunge stemmed from health issues severe enough to have halted her college education. At the end of the sixth year, he struck third-time luck. She accepted. That was after a stroll down Breach Candy’s sea-hugging rockery and promenade dubbed Scandal Point for a romantic, wartime association. It was the niche for sweet rendezvous, where soldiers stole quiet sunset moments with their girls, amid the clamouring cawing of crows nesting for the night.

Dating done, miya-biwi raazi, they needed to celebrate. Off they trotted to Bombelli’s down the road (where Amarsons-Premsons stand), to seal the deal over vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce. For long years after, this is our old-fashioned choice of dessert when any cause for celebration presents itself in the clan.

Bide-a-Wee, the family cottage in Kodaikanal for their honeymoon

Bide-a-Wee, the family cottage in Kodaikanal for their honeymoon

My jubilant folks were hardly alone. The passion and proposals that Freddy and Betty Bombelli indulgently witnessed, at their Breach Candy and Churchgate branches, warmed the hearts of the Swiss restaurateurs. Propelling plenty of prem kahaanis, Bombelli’s cast a spell over everyone trooping in. My folks were no exception.

The day after deciding to get hitched, they registered for JJ Rodriguez’s dance class. After feather-footed Joao Joaquim Rodriguez of Margao wowed the city with his school in 1951, it was de rigueur to show the object of your affection smooth ballroom moves there. Couples of every vintage happily headed to Sethna House on Barrow Road—Allana Road today, facing Electric House on Colaba Causeway—practising to pirouette and glide with grace. Trust history-loving Mum to challenge us as she narrated how they enjoyed this, despite both having two left feet. She asked, “I wouldn’t know, but don’t you want to find out why it was called Barrow Road?” Phiroze and I shrugged couldn’t-be-bothered “Nahs”.

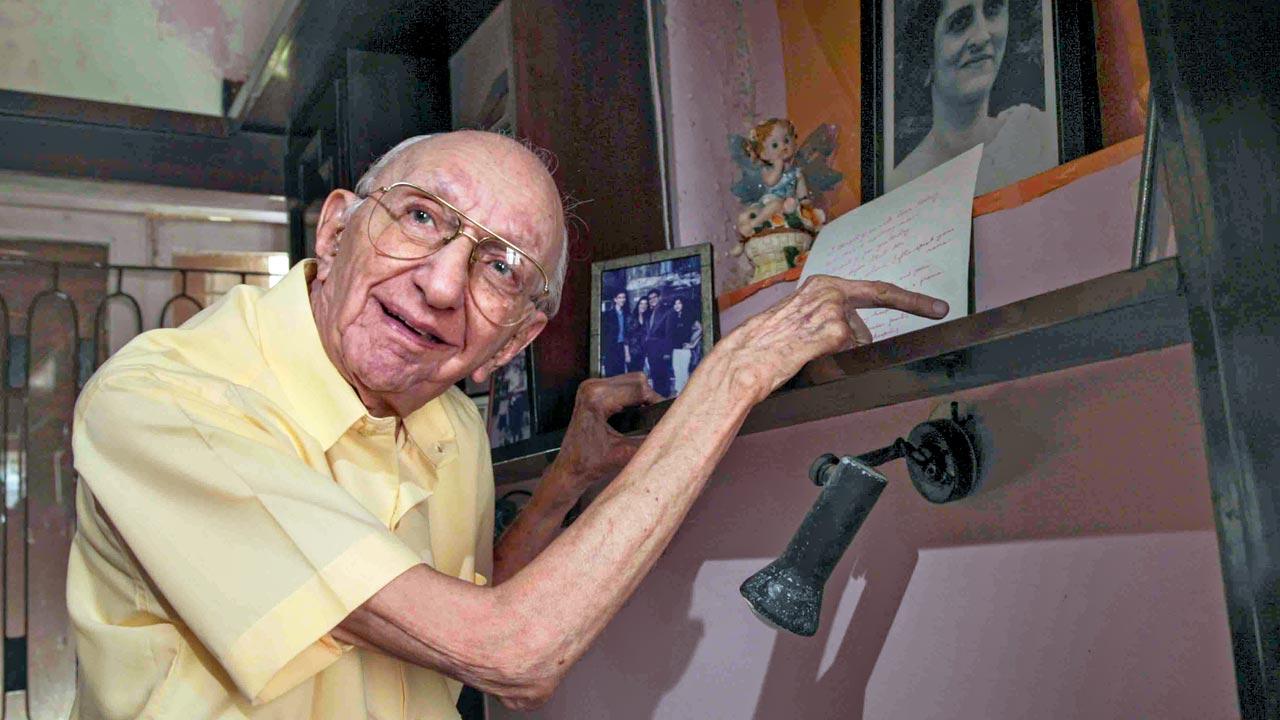

Reading the memorial poem dedicated to his wife, under her portrait. Still from the documentary, The Ninety-first Symphony, by Rafeeq Ellias

Reading the memorial poem dedicated to his wife, under her portrait. Still from the documentary, The Ninety-first Symphony, by Rafeeq Ellias

Older and wiser, half a lifetime later, when I began researching Allana Road for this column, I did have to check. Barrow Road was constructed by the Bombay Port Trust; HW Barrow, chief reporter at The Times of India, was Municipal Secretary from 1870 to 1898.

The two also decided to learn a foreign language together. German was too guttural— “Every word long as a sentence,” groaned Dad, nixing it. For Italian, there were only average self-study courses then. They finally enrolled as beginners at Alliance Francaise. Conjugating irregular French verbs frustrated him. Challenged to handle even that basic level, he came to class joking that he feared the tutor would fling a well-aimed copy of the Modern French course Dondo textbook at him. She, on the other hand, soon became the teacher’s pet, picking up nuances quicker than most. Loyally, she rallied as his grammar cheerleader—“It isn’t you, Homi. They shouldn’t race ahead at this fast pace.”

After duly visiting various elders of the extended Dastoor clan in Navsari, and their 1959 marriage in Albless Baug at Charni Road (named for Edulji Framji Albless, who earned the last name for his kind manner of greeting everyone “God bless you all”, which compressed to “Albless”), the newly-weds got a shock. The assigned photographer claimed everything shot was ruined. For someone who routinely collects photographs for oral history work, I’m still coming to terms with the sad reality that my own family album has slim pickings.

Ever the optimist, Dad simply said “Forget it” and whisked Mum off to Kodaikanal for a week. A diligent assistant to Darab Tata, JRD’s brother, before joining Tata Textiles, he was pleasantly surprised to have the boss instruct, “Dastoor, what’s a single week of honeymoon, take another two!”

Honeymoon done and house hunt accomplished, they settled into discovering each other’s irks and quirks in that deep, disconcerting way that fully surfaces when cohabiting replaces courting. Homemaker extraordinaire, Mummy tended to a largish joint family—which included a trio of sisters-in-law a generation older than her—with good nature, common sense and practicality.

Zealously, she scrimped and saved household expense amounts for her man’s sole indulgence: buying music or books on music. Tucked in her cupboard drawer were little envelopes labelled “Rent”, “Salaries”, “School fees”, “Groceries” and “Medicals”. There was a last envelope: “Homi’s music”. Phiroze and I could dip into any of the rest of the envelopes for an extra rupee or two with which to boost flattened pocket money change in our piggy banks. We did not dare touch “Homi’s music”, that’s how vigilantly she guarded that bunch of notes.

If Mum missed out on realising her dream of a career in law, she seldom mentioned it, but she could argue all right. And admitted she had a problem: reluctance, bordering on inability, to apologise. He, instead, said “Sorry” with endearing promptness. What’s more, believing that nothing proved a better panacea for sulks and the promise of peace than the sonority of music, he played favourite pieces composed by greats they mutually admired.

Music was everywhere in our home, booming from a Garrard player I still have. The volume, upped for listening pleasure, ensured its strains reached the corners of each room. Bach to Brahms, Schubert to Sibelius, Mozart to Mendelssohn, their brilliance was second breath to us.

This happened literally from the cradle. Suffering the first-child syndrome, Phiroze was handled with ginger nervousness. Being second, I received more confident parenting. After Mummy got over slight initial alarm, Dad blithely parked my pram in the living room below stacked shelves of records rocking me to sleep. He actually recommended the loud bedtime routine to friends with kids, proud that his baby daughter scrunched shut her eyes within a minute of hearing the Merry Widow waltz’s melodic opening bars.

Not a day went by without the beautiful sound of music. Composers became family members. A diehard devotee of Beethoven and Jascha Heifetz, Dad fervently wished his children could share birthdays with the virtuosos. Phiroze came in close, a day after wizard-of-the-violin Heifetz’s janamdin, February 2. More disappointingly, I arrived two entire weeks ahead of Beethoven’s birth date, December 16.

Not only did the maestros’ photographs hang beside our ancestors’ portraits, but their birthdays had to be properly observed. We tucked into festive breakfasts of sweet sev and ravo—dishes Parsis prepare on auspicious occasions. Guess who gamely kept track, marking those red-letter days way ahead on the calendar and rustled up the treats in a kitchen fragrant with freshly fried kishmish and kaju slivers? Amazingly supportive, wonderful at encouraging what was enjoyed by us all, ticking checklists of ingredients, Mum worried, “Are there enough almonds? Rava? Raisins?”

I teased that she was more carefully stocked with badams for Beethoven’s birthday than mine preceding it.

Mummy made sure the four of us observed an every-Friday ritual we looked forward to: “Bringing Daddy back” from work in Fort. We raced home from school in Bandra, boarded a Churchgate local and skipped onward to his Tata Textiles office at Bombay House, now in its centenary year; George Wittet designed the headquarters this industry giant established in 1924.

We would walk hand-in-hand to Marosa, a stone’s throw from Flora Fountain. The neighbourhood cafe for cosy chatter was as much the haunt of office-goers as it was the adda where Raj Kapoor conferred with his cinematographer Radhu Karmakar and music directors Shankar-Jaikishan. It served generous platefuls of chicken patties, billing customers for those eaten.

Ma slipped away six months short of their golden anniversary. Dad passed on ten years after, at 95. Every single morning, he recited aloud—almost like a prayer—a tender ode to her. Rafeeq Ellias filmed him doing so on a morning when he shot the documentary, The Ninety-first Symphony, capturing the essence of the man who wrote Musical Journeys, a bestselling book on Western classical composers, with a foreword by Zubin Mehta, at the age of 90. The poem read:

“I thought of you with love today

But that is nothing new,

I thought of you yesterday

And days before that too.

I think of you in silence

I often speak your name,

All I have are your memories

And your picture in a frame.

Your memories are my keepsake

With which I will never part,

God has you in His heaven

I have you in my heart.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!