Gone are the days when pace bowlers used to smile at the sight of Caribbean tracks

West Indies’ desperate search for fast bowlers, futile since the exit of Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh at the start of the 21st century, has been reactivated.

West Indies’ desperate search for fast bowlers, futile since the exit of Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh at the start of the 21st century, has been reactivated.

ADVERTISEMENT

At their recent meeting in Barbados, West Indies Cricket Board (WICB) directors charged the cricket committee to have another go at coming up with suggestions of how “to prioritise the development of fast bowlers in the region and for the West Indies team, recognising that the majority of the overs in regional tournaments are bowled by spinners and is impacting negatively on the production of fast bowlers for the West Indies team”.

Enviable domination

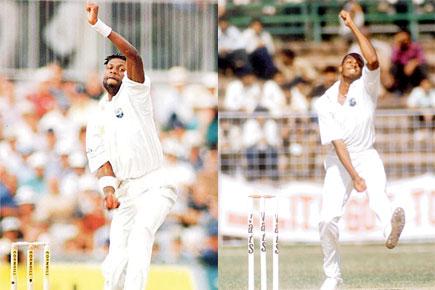

Michael Holding, “Whispering Death” of the feared pace quartet of West Indies’ unprecedented domination of the global game in the 1970s and 1980s, and Ian Bishop, his worthy successor of a decade later, agree with the general view that improved pitches are an essential factor in answering the board’s directive.

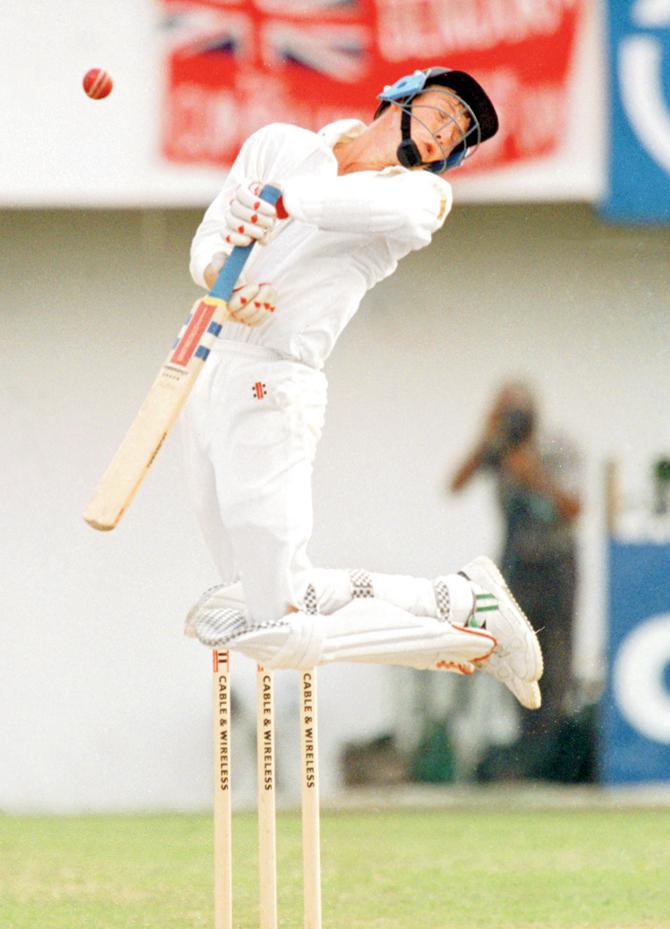

England batsman Mike Atherton takes evasive action while facing a bouncer from West Indies fast bowler Courtney Walsh in the Jamaica Test at Sabina Park, Kingston on February 21, 1994. Getty Images

Holding recommends India as an example to follow; Bishop is less convinced. “When I first played against India in the Caribbean in 1976, their spinners, Bedi, Chandra, Venkat and Prasanna, bowled all but a few overs between them,” Holding recalls. “Madan Lal, Mohinder Amarnath and Ekie Solkar were medium-pacers just there to take the shine off the ball.”

Once it dawned on the Indian board that such an imbalance placed them at an obvious disadvantage in different environments overseas, he says, it deliberately set about upgrading their pitches. At the same time, the MRF Pace Foundation was formed under the guidance of the great Australian Dennis Lillee.

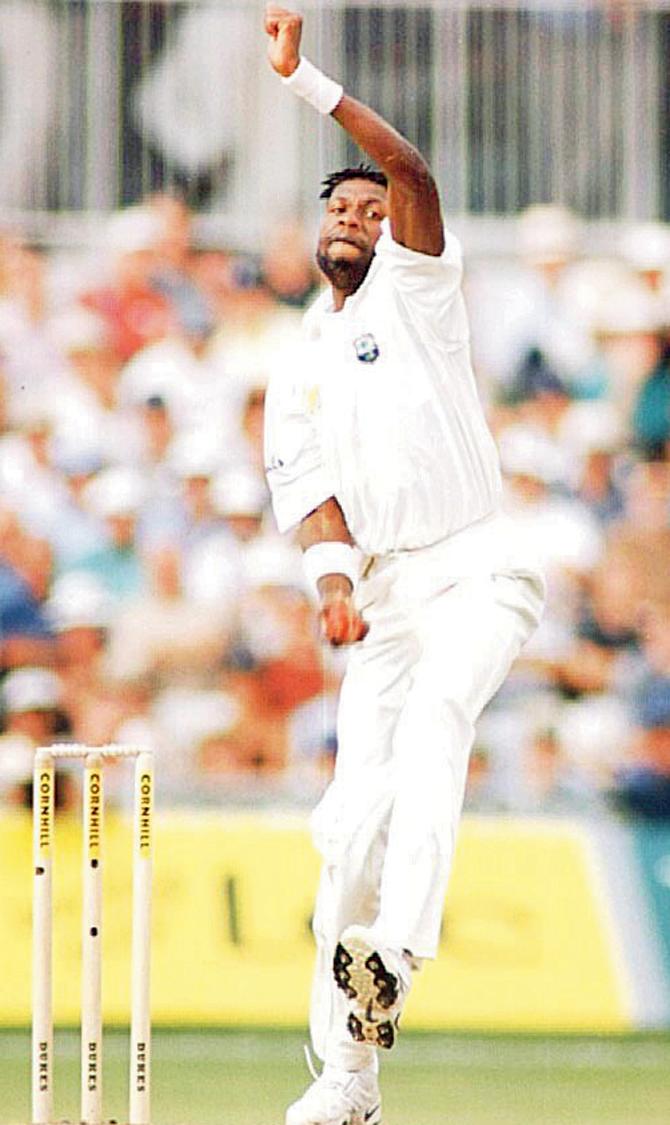

Courtney Walsh

While Bishop, like Holding now a respected television analyst, also regards better, fair surfaces as central to the development of a new generation of fast bowlers, he is quick to add that does not mean taking India’s route.

“We don’t want to do like India and make green seamers at domestic level,” he says. “In India, the balance has shifted to where spinners are now almost extinct.”

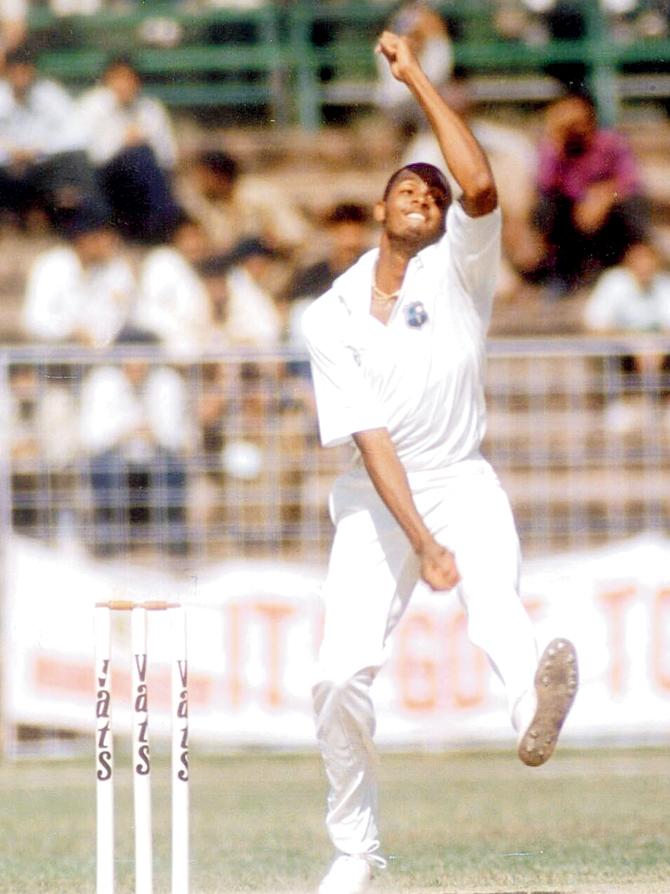

Curtly Ambrose

Holding points out that young men with all the physical attributes for bowling fast are turned off by the slow, low pitches presently found on most grounds in the Caribbean.

“Not all the surfaces we had to bowl on coming through regional cricket were pacy and bouncy but most gave you a chance,” he recalls.

There are other considerations. “Spinners are given a false sense of their worth and batsmen are restricted in their strokeplay on such pitches,” Holding adds. “The long and short of it is that every sport needs the best conditions to flourish.”

It has become a familiar scenario, diminishing the stocks of what, from the earliest days, pace was an essential element in West Indies strength. Since Walsh decided in 2001 that, at 37, after 132 Tests and a record 519 wickets, his body was no longer fit enough for the game at the highest level, West Indies Test teams have included 18 new fast bowlers.

Only three have taken more than 100 wickets — Fidel Edwards 165, Jerome Taylor 122, and Kemar Roach 120. Only Roach, at 27.83, and Jermaine Lawson, 29.64, average less than 30 runs a wicket.

Bishop makes the point that better pitches at major grounds would encourage only those fast bowlers already playing first-class and international cricket.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!