Australia's foremost cricket historian Gideon Haigh remembers legendary cricketer and commentator Richie Benaud, says he stood out for his detachment and even-handedness when calling the game

It turns out that the last occasion on which the cricket public heard Richie Benaud was the thirty-second recitation he delivered in honour of the late Phillip Hughes, played at Adelaide Oval before this summer’s First Test.

ADVERTISEMENT

Benaud summed Hughes up in a few, well-chosen words, with a paternally warm concluding sentiment: ‘Rest in peace, son.’

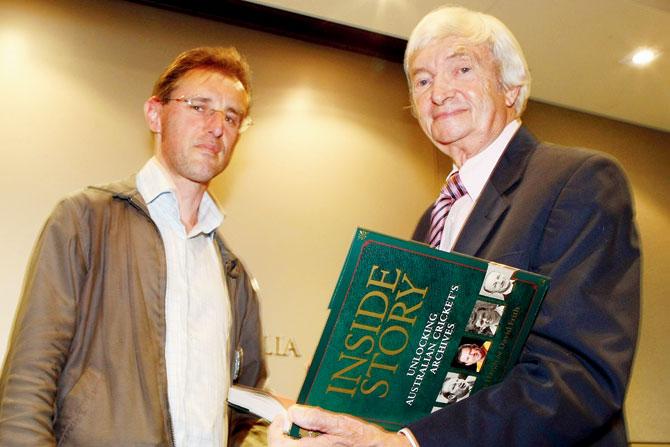

Gideon Haigh (left) with former Australian cricketer Richie Benaud on October 22, 2007. Pic/Getty Images

It also, somehow, reflected Benaud’s relationship with cricket, and with Australia. When you heard it from Benaud, that made it official, credible, true, even in the ghastliest circumstances. He had been there; he had seen it; but the sun would rise on cricket tomorrow, and the game would abide.

Had a politician been able to achieve such trustworthiness, there would have been no need for elections, or even opinion polls. Benaud’s was the stock in every portfolio, the household brand in every home.

Fidelity to commentary

That was partly his sheer durability over half a century at the microphone, partly his unstinting fidelity to his craft.

Benaud connected cricket to the inception of broadcasting, upholding a principle articulated first by Seymour de Lotibiniere, who originated cricket commentaries on the BBC in the 1930s: “Don’t speak unless you can add to the picture.”

That if it didn’t matter he didn’t say it invested Benaud with a special authority, because after a while the opposite became true: that if he didn’t say it then it didn’t matter. The fashions changed, of course, and at times in later years Benaud’s commitment to understatement seemed one out against the tide of garrulousness.

A story circulated, perhaps apocryphal, that he did a stint with two other commentators in which he did not actually utter a word, there being little opportunity and no obvious need.

But he never deviated from his approach, regarding it half-humorously. I once went to interview Benaud with a photographer, who helpfully suggested that the subject imagine he was commentating on a dramatic Test match. That might make the interview difficult, Benaud commented dryly: “If it was me, I probably wouldn’t be saying anything.”

Even-handedness

As cricket commentary grew ever more partisan, too, to accord with the imagined ‘passion’ of the fan, Benaud stood out for his detachment and even-handedness.

Perhaps that was also training, or at least habit, from more than four decades alternating hemispheres.

But Benaud was on nobody’s side, except cricket’s, and perhaps cricketers. For underlying that sang froid was a sympathy for the players and their lot.

It is hard to recall him ever damning an individual, condemning a team, deploring a controversy, slamming an indiscretion.

That wasn’t his purpose, of course. The howls of execration could be led by anyone. Benaud’s judgements were considered, circumspect, usually terse but seasoned with an appreciation that cricket was difficult, success and failure sometimes not so far apart, and luck blind.

One of his most famous mots, in fact, was the one about captaincy being 90 per cent luck and 10 per cent skill, qualified with the advice not to undertake it without the latter.

Benaud knew, of course. Even if he was hardly ever asked about his own cricket, and spoke of it voluntarily still less often, all of us were aware of his stature, detectable in the mellowness of his musings, and the audible deference of his colleagues.

For them as well as us, he was the mediator between past and present, almost continuity itself — confidante of Sir Donald Bradman, intimate of Kerry Packer, long-time employee of Rupert Murdoch, the cricketer who blazed the trail from crease to commentary box followed by so many others, the figure who kept his head while all about him were losing theirs.

There was a cultural shift at work here too. Benaud spaned the transition in the broadcasting of cricket from a time when the game was covered by national broadcasters as a kind of public trust to a day when the game sold the rights to televise it for vast sums — as a consultant to Packer’s World Series Cricket, he aided and abetted the change. That fundamentally altered the role of the commentator, so that a tension now inheres. The game the caller describes is also the product he is selling.

Praise is now a kind of investment in the brand, while criticism must be tempered by the considerations of commercial value.

Balancing act

With his natural moderation and understatement, Benaud balanced his roles as effectively as anyone in history. At times, so irresistible were the market forces, even he could be seen trending towards cliché, obediently spruiking television shows for Nine, mouthing ‘marvellouses’ for Cricket Australia television advertisements. But in general, knowing he had our trust and respect, he never endangered it.

To whom will cricket now naturally turn when seriousness and reflection are required? It is not an easy question to answer.

Rest in peace, Richie.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!