A new exhibition, set to open in three weeks at CSMVS, will give visitors a comprehensive look at India and the world

We join in on the installation of a Mauryan pillar capital, which has travelled all the way from Bihar Museum to Mumbai's Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS). Weighing nearly a colossal 700 kg, the relic needs a dozen pair of hands, a resounding "Om" from the production staff, and bright focus lights to get it settled on its stand. CSMVS's director, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, watches with bated breath, and tells us, "It's like a Bollywood film set."

ADVERTISEMENT

Only, what's before our eyes, is no fiction; it's all historical fact set in stone, ceramic and metal as an ambitious exhibition, presented collaboratively by CSMVS, The British Museum (London) and National Museum (New Delhi) counts down to its opening on November 11. The ambitiousness of the exhibition is reflected both in the number of objects as well as its title, India and the World: A history in nine stories. What appears at first reading like a chronological historical survey of India, the exhibition is in fact a web, offering parallels and comparisons across the world, right from the birth of the earliest civilizations.

Conceptualised by Mukherjee and art historian Neil MacGregor, former director of the British Museum, the exhibition has been in the making for nearly three years, and found shape under curators Naman P. Ahuja and JD Hill. Given the vast nature of the subject that continuously posed the threat of getting off-track, the curators' guiding principles were these. That the 'World' needed to be represented as equally as the objects from India. That the exhibition was not about the most famous or well-known objects, but about the stories they tell. "The hardest part of making any exhibition is that you always want to 'just add one more object'," says Hill, a research manager at The British Museum, who is best known for being involved with cross-museum projects. He spent four years as lead curator for British Museum and BBC Radio 4's project, 'A History of the World in 100 Objects' by MacGregor in 2010.

Showcasing history

To condense millennia-worth histories into a nutshell, the exhibition, which has over 210 objects, is sectioned into nine parts, each an important moment from the subcontinent's past. Within each section, artefacts from India will have the company of artefacts from across the world.

"We cherry-picked the most interesting objects so that we can see what was happening in the rest of the world at the same time as India. The objects allow correspondences and differences to be noted. They also satisfy curiosity: For instance, we all know about the history of the Pyramids. What was India doing at that point? Or, can we make valid connections between Mauryan architecture and Persepolis?" says Ahuja, professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He is most noted for his exhibition on The Body in Indian Art and Thought, shown at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels and the National Museum in Delhi in 2013-14.

As its starting point, the exhibition chooses the very birth of civilisations, with Shared Beginnings and First Cities. From here on, it paces through to Empires and Courtly Cultures, before ending with Time and Space. India and the World also nods to trade links across the Indian Ocean. "We wanted to remind people that international connections are not a recent phenomenon. They have a long history, and India has always played a major role in this," says Hill. For example, Indian pepper was used to flavour food on the northern reaches of the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago. A Roman pepper pot in the exhibition shows that the valuable spice was traded across the Indian Ocean, often in Indian ships.

With objects sourced from The British Museum, known as one of the only four encyclopedic museums with world collections, visitors will get to glimpse these treasures, alongside those from Indian institutions. Ahuja also feels that this is a chance for visitors to appreciate the aesthetic quality and historical relevance of other lesser-known objects. "We hear a lot about the Amravati Marbles in The British Museum [which Telengana recently wanted "returned" to India]. In this exhibition, we have a work from Phanigiri, in present-day Telengana, which doesn't just rival but actually supersedes the Amravati pieces. Rather than clamouring for repatriation, we need to pay attention to these neglected sites and pieces," he asserts.

Curators Naman Ahuja and JD Hill recommend these picks from India and the World that visitors should catch:

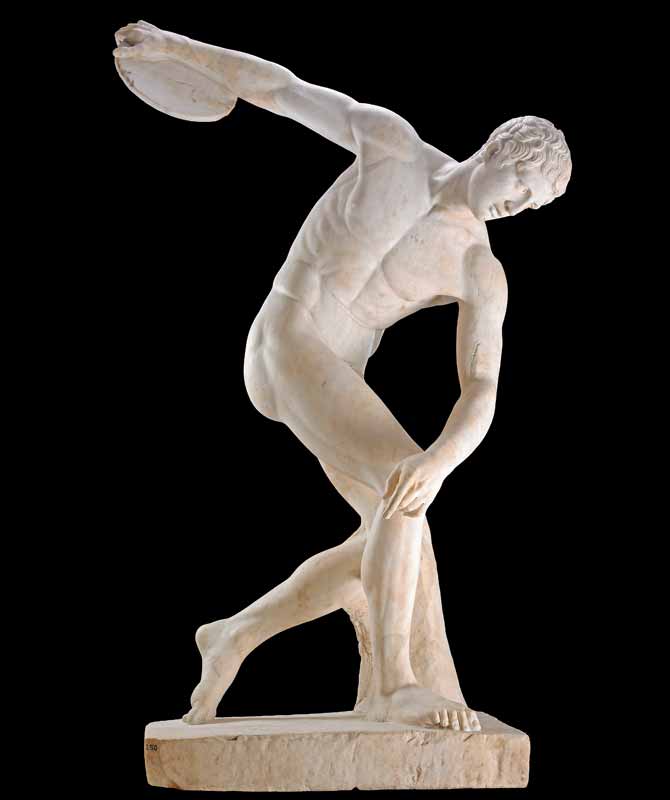

The Townley Discobolus, is about two millennia old and one of the most famous sculptures from the ancient world. The statue of an idealised athlete will be placed in the atrium of CSMVS for India and the World, along with other sculptures that symbolise strength and speed. PIC/ © Trustees of the British Museum

Kalamkari textile, AD 1640–50, Golconda: This textile reveals the multicultural nature of Indian Ocean trade. A prince is seen in a garden pavilion in Persian attire. He exchanges a flower for wine held by a woman in a European-style hat. An Indian ascetic is shown contemplating a pineapple, a new import into India on account of the Indo-Portuguese trade from South America. PIC/NATIONALâÂu00c2u0080Âu00c2u0088MUSEUM

Jahangir receiving an officer by Rembrandt, about AD 1656–1661, Holland: A drawing of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir copied by the celebrated Dutch artist Rembrandt. Courtly life was often the focus of Mughal miniature paintings, which fascinated Rembrandt. Rembrandt has paid great attention to Mughal clothing, but has altered the perspective in keeping with European artistic styles. PIC/ © Trustees of the British Museum

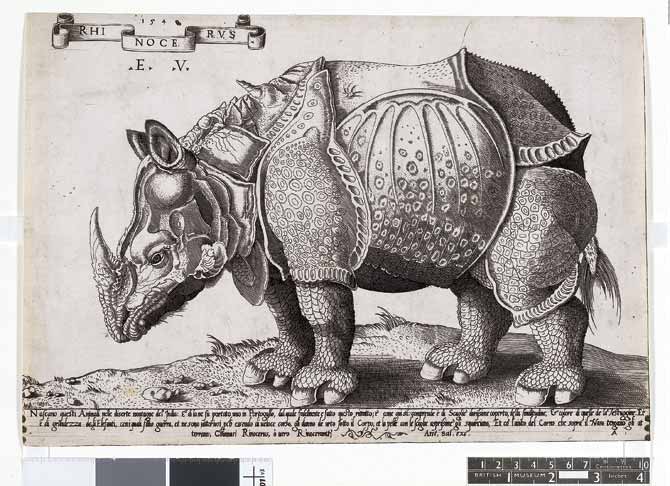

Rhinoceros, after Dürer, AD 1548, Italy: Given by the Sultan of Gujarat as a gift to the Portuguese, this rhinoceros was the first to be seen in Europe since the end of the Roman Empire. Albrecht Dürer created a print of the rhinoceros, on which this later copy is based, despite not having seen it. The animal was later sent as a gift to the Pope, but perished on its way. PIC/ © Trustees of the British Museum

Head of Roman Emperor Hadrian,

AD 117–138

London: The heads from three portrait statues — a Kushan king, Hadrian and Alexander the Great — have been placed together to show how the image of the emperor was used by different civilisations to promote a cult-status for them. PIC/ © Trustees of the British Museum

Persian Achaemenid relief, 599–400 BC, Iran: This relief comes from Persepolis, one of the capitals of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, which stretched from Turkey to Pakistan. It shows a soldier holding a spear, wearing a long robe and a pleated headdress. PIC/ © Trustees of the British Museum

An edict of Emperor Ashoka, about 250 BC, Nallasopara: This fragment comes from the ancient port town of Sopara in Thane, near Mumbai. Ashoka sent one of his missionaries to Sopara to spread the message of the path of dhamma, which gives merit that lasts lifetimes. PIC/CSMVS

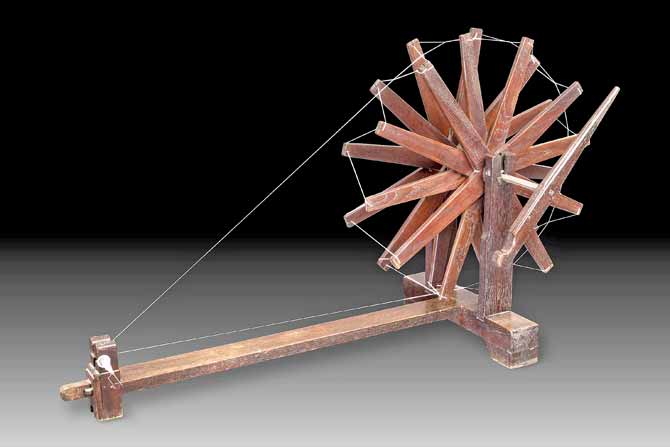

Charkha, 1915–1948, West India:

The charkha, or spinning wheel, was one of the most powerful symbols of Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy and politics. It was both a protest against Britain's attempts to deliberately undermine Indian weaving and also a symbol of self-reliance. PIC/Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!