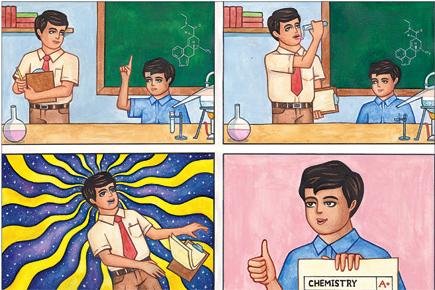

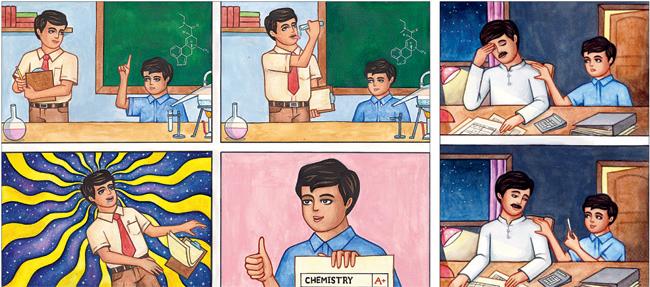

Adarsh Balak, a series of illustrations by Priyesh Trivedi, takes the ideal world of the boy in the virtuous school charts and turns them on their head — irreverently. Trivedi has garnered 26,000 followers on Facebook in a month. The Internet sensation tells Kareena Gianani and Nikshubha Garg that what is subversive to most is “normal” to him

Chemistry teacher

Priyesh Trivedi arrives for our meeting at a suburban café, looking baffled. Not quite the mien we expect of the guy who, in his illustrations, makes a schoolboy offer a joint to his visibly-hassled father, and one who tricks his Chemistry teacher into tasting acid to get a straight A+ in the subject.

ADVERTISEMENT

(Left) The boy tricks his Chemistry teacher into tasting acid to get a A+ in the subject. (Right) The boy offers a joint to a visibly-hassled father

However, terms such as ‘internet sensation’ and ‘overnight success’ still leave the 23-year-old Borivli resident nonplussed. Trivedi is dressed in a jeans and grey shirt, and wears a sling bag which he shrugs off as soon as he sits down. His dreadlocks are casually tied at the back. “I did not expect this response to Adarsh Balak. I’ve just squiggled what was in my head. I never planned to make a point with these illustrations or make it this subversive movement people are telling me it now is,” he smiles hesitantly.

We raise our eyebrows — is Trivedi really that surprised at how his irreverent (and unique) illustrations have taken the online world by storm in a month, enough to garner 26,000 followers? And that some fanboys on his Facebook page tell him they want to grow up to be like him? He fervently says he is.

Unlike his art, which is outspoken, unapologetic and direct, a conversation with Trivedi is most likely to be delightfully disjointed. His ideas run amok before his words can catch up, which he then ties around neatly. The chat takes us to psychedelic art (which he feels is transcendental), takes a detour to industrial use of hemp in India, and comes back to where it all started — to his first brush with art, quite literally.

Trivedi is a self-taught artiste whose first memories are of drawing birds and landscapes on any blank space he could find around him. “My art mentor was at her wit’s end because I wouldn’t touch human anatomy,” he remembers.

It was Surrealism that piqued him most, and set his fertile imagination free. As a teenager, Trivedi remembers being awed by the whimsical works of Surrealists such as Salvador Dali. “To me, it was the most evocative example of rebellion from one-dimensional art movements such as Renaissance. Dali and his contemporaries made art which exhorted people to look beyond the obvious. The message set me free,” says Trivedi rather passionately.

Trivedi, who is a freelance game artist, found further expression in Dadaism and in propaganda posters of Soviet Russia, and Germany before and during World War II. There is little Trivedi is not curious about when it comes to exploring his art and letting an idea wander. He says he shuns literal, simplistic interpretations of religious texts, for instance, and tries to understand their myriad interpretations. “Take paganism, for instance — it has been distorted to an extent that most people associate it with the devil,” he said, gesticulating fluidly.

Little wonder then, that the enduring relationship between man and nature in shamanic cultures, such as the Native Americans, Aboriginal Australians, deeply fascinates Trivedi, who wishes to delve deeper. “These cultures still have an innate connection with nature. Their visual art affects their life, and vice versa. Ancient cultures, for instance, didn’t believe they had a right to ban certain plant, like we do now. They simply used it wisely,” he explains.

We think of the boy offering a joint to his father in Adarsh Balak. “I am just demented that way,” he says resignedly. “Trust me, that’s my ‘normal’!”

He laughs throatily and says that came from his bafflement at those old, India Book Depot charts which illustrated the life and habits of an ‘ideal’ boy. Trivedi found them cryptic as a child, and he often wondered at how dissimilar he was to that young boy. “The boy’s way of life fascinated me. He woke up, brushed his teeth thoroughly touched his parents’ feet, and did no wrong,” he says, without a hint of a smirk. Trivedi laughed at some, and was plain alarmed at the one which encouraged school boys to join outfits to be an ‘adarsh balak’. Those charts, to Trivedi, were stereotypical but he did love their old-world charm, and itched to do something with the pastel colour scheme and the glazed-eyed characters.

One fine day, in October 2013, he began recreating the style in the charts and wrote “T for Toke” above an illustration of the school boy rolling a joint. “I just put it up on Facebook for fun. And it went viral,” he says and shrugs almost shyly.

We get that Trivedi does not think his art is subversive, but we aren’t sure whether he is taking the mickey out of us when he says he has never thought about anybody taking offence to his illustrations. “Is it offensive? I don’t think so. Art is not so literal. What is offensive to you might be evocative for me. I am not trying to shock people, or offend anybody. Why would I? If just speaking my mind has that effect, I think it is best ignored, isn’t it?”

With Adarsh Balak having a huge fan following and persistent requests of updating new illustrations pouring in every day, Trivedi must maintain composure. “I get a lot of requests to update faster than usual but for now, I plan to update one illustration a week. You can’t rush these things,” he signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!