Arun Ferreira's prison diary is an intense account of police atrocity and a corrupt state. He tells Kareena Gianani that injustice has only strengthened his will to fight for political prisoners incriminated by India's draconian laws

Colours Of The Cage is an unsparing account of the nearly five years activist Arun Ferreira lost forever in Nagpur Central Jail after being accused of being a Naxalite. In May 2007, Ferreira was forced into a car by 15 men, beaten and blindfolded as he heard his abductors discussed the option of killing him off in an encounter. Till September 2011, Ferreira languished in prison while nine cases were slapped against him.

ADVERTISEMENT

On one level, one expects a prison diary to be searing and revelatory of a state’s corruption — and Ferreira’s is that.

Arun Ferreira is studying criminal law to help political prisoners. Pic/Bipin Kokate

But what makes his memoir most compelling is its pithy, unembellished prose. Ferreira lets his experience do the talking. Like this — ‘Both my legs would be forced wide apart and a cop would stand on my thighs so that I couldn’t bend them. Sometimes my interrogators would pinch my or pull my hair or pierce the skin under my nails with pins’.

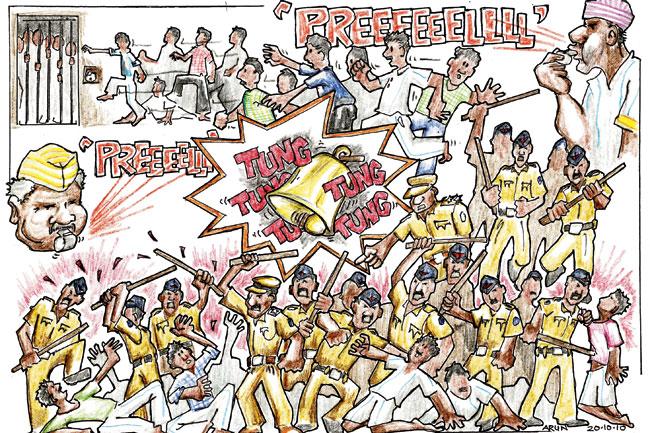

The book has illustrations depicting prison life, which Ferreira attributes to his intense state of despair. Ferreira began drawing to — ironically — cheer his toddler son up by illustrating superheroes in his letters back home. He then began sketching the yard where they played volleyball and other sketches for the prisoners whom he taught geography, English and maths. “We were denied a geography textbook because it had a map of Nagpur. What if we used it to escape from prison. Naxalites are capable of such things…,” says Ferreira wryly.

A year ago, to write a book on life in jail, Ferreira went through a harrowing time while sifting through the letters he wrote back home to remember details. “I could see how much I had downplayed the details to protect my family from anguish,” says Ferreira.

The activist also decided not name the policemen who tortured him ruthlessly. “The book’s aim is to expose the brutality of the system. Taking names would expose some officials, but the real tormentors higher up will remain shielded.” He says he also wanted to essay the characters he met to throw up social or political issues. For instance, in the book, Ferreira has a long discussion with a policeman who frequently beat up prisoners and broke a lathi or two during each beating, which was called ‘Shyam Bhajan’. “He told me how prisoners — political and otherwise — must not have human rights. Jail, he sincerely explained, must soften them,” remembers Ferreira. He also recalls a debate with a prisoner who believed that if prisoners were a vote bank for politicians, their plight would improve.

Often, Ferreira writes about his thoughts on befriending those in jail for serious, sexual offences, including Allan Waters and those responsible for the Khairlanji massacre. “Compulsion — that’s all that’s there to it. The isolation, the nature of the place compels you to speak to whomever you can,” he explains. As a political prisoner, Ferreira deeply yearned for dialogue with other political prisoners, debate, and news of the outside world.

Merciless abuse in prison has only strengthened Ferreira’s resolve. He earned his postgraduate degree in Human Rights in prison, is now studying to become a criminal lawyer to work with political prisoners, and publishes illustrations on police atrocity in the online magazine, DailyO. “They couldn’t break me. Now, when I read about cases of torture, I can read between the lines and determine the officials’ real motives. A suicide in the Anda cell, for instance, is rarely just that. I use my experience to help others, who are not even as privileged as me — tribals, dalits for whom this torture is rule, not an exception,” he says.

An illustration Arun Ferreira drew in the Nagpur Central Jail

A lot has changed in the five years he spent in jail — a reality Ferreira is not stranger to. “I’d say most things have got worse — the platforms to voice opinions and critique are few, and shrinking. There is still no respite from draconian laws such as MCOCA and Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, which are often used to crush dissent,” says Ferreira.

The only silver lining he sees is that political prisoners are, again, in the spotlight, and the Free Binayak Sen campaign is a case in point, says Ferreira. “People spoke about political prisoners in Indian history during Independence, post Naxalbari, the Emergency and now during Binayak Sen’s release. I don’t want to make my prison experience sentimental — I want to be the rallying point to fight for the cause,” says Ferreira.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!