What happens when some photojournalists across India ditch their swanky DSLRs for a while and capture everyday wonder through Instagram? In an exclusive chat with Kareena Gianani, the founder of Katha Collective speaks about his new initiative which will curate sensitive, opinionated photo essays

Mood

Ritesh Uttamchandani is deputy photo editor at a news magazine, but has none of that mobile-phone-photography-is-not-real-photography disdain when he speaks of the medium. “I can use Instagram to take inane pictures of my caramel custard, or to capture a physically-challenged man I meet outside Churchgate station who was there because that’s the only station to have a Western-style toilet,” he shrugs.

ADVERTISEMENT

In #traindiaries, Anushree Fadnavis’ photographs the many moods of women commuters in Mumbai local trains. Tempers flying, women who grin and bear it all, some who lose patience when frequently poked in the shoulder by those who want to know where they will disembark — Fadnavis’ smartphone is there to capture it all Fadnavis captures a mother who finds a way to keep her sleeping child close and operate her mobile phone at the same time

Uttamchandani knows just how much the diminutive lens of a smartphone camera can capture compared to the formidable black bulk of a DSLR. So, on August 19, he launched the Katha Collective, to showcase Instagrammars who would photograph short and long photo essays exclusively with their phone cameras.

A woman’s reaction to a flying strand of a co-passenger’s hair in her face

“I feel photojournalism in India is yet to take risks, and come up with engaging and experimental work. Through the Katha Collective, I want to curate meaningful images using a new medium, which are, above all, sensitive. Instagram is not frivolous — it is challenging, with its shutter lag and lack of light control,” he adds.

Koli women silently praying for a safe journey as the first Virar local comes to life with a rumble at 3.25 am

The series kicked off with the first photograph of Anushree Fadnavis’ 25-picture essay on the women in the second-class compartments in Mumbai’s local trains. Fadnavis captures the ethos of the Mumbai local — women mumbling prayers when the first train out of Virar rumbles into motion — and commonplace gestures, like that of a lady scrunching up her face while manoeuvring her way through the peak-hour rush in a train.

Ritesh Uttamchandani, founder of the Katha Collective

“We are so obsessed with photographing Mumbai’s quirks and oddities in ‘hatke’ images, that we have forgotten the wonder in the city’s everyday life. Mumbai’s stories don’t have to start at Colaba and end at Kala Ghoda. Where are the stories of the migrants, of a sandwichwalla who travels from Borivli to serve his fare to the Tommy Hilfiger-toting corporates at Nariman Point?” asks Uttamchandani, when asked about the diversity he hopes the collective will capture in the coming months.

Arti, the 14-year-old daughter, has stopped going to school and has no say in the matter.

The Katha Collective will feature long, opinionated photo essays by Uttamchandani, photographers Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Zishaan Latif, Haziq Qadri (on life in Kashmir), Prince Saimah (on the changing face of Tezpur), Natasha Hemrajani (on Pune’s Bohra community) and Mubeen Siddiqui (on Delhi’s Afghans) and others.

The istriwallah’s young son, Latif says, is reluctant to take over the reins of the job and wishes to get a full-time job.

“The biggest challenge for a photojournalist is to not be forgotten and look at what s/he is competing with — which is anybody with a mobile phone today. When Bal Thackeray died in November 2012, the first photograph that went viral was clicked by a smartphone camera — not one by a certified, equipment-proud photographer. That’s what we are up against now,” says Uttamchandani.

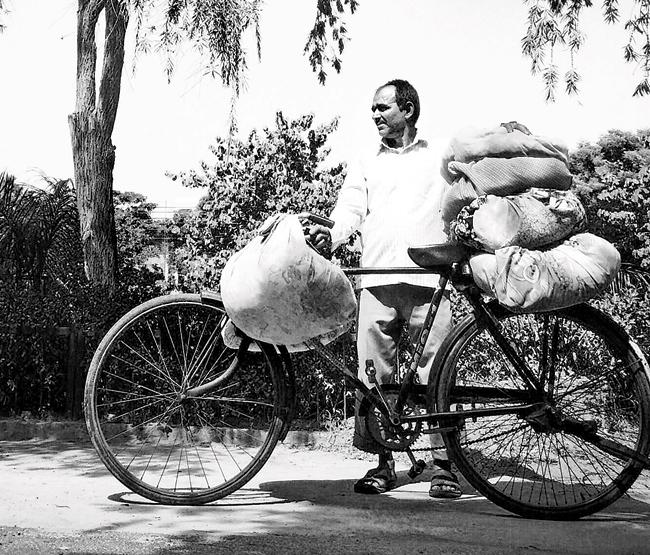

These photographs are part of Zishaan Latif’s upcoming photo essay, tentatively titled ‘#istriwallah’, on the Katha Collective. Through a family of four, all of whom help the father, who has been an istriwalla in Latif’s housing colony in Noida, Latif hopes to capture a changing neighbourhood.

#traindiaries is my visual diary, an equivalent of me coming home after commuting in the Mumbai local and scribbling in my journal. Katha Collective allows photographers like me to tell our life stories. The ladies’ second class coach is a space where everyone is inter-dependent. Over the years, I have seen deep relationships being forged here. I have watched sweaters knitted from start to finish, women groom themselves for work from scratch, and catch up on sleep. Full meals are prepared on the move, only short of the final tadka. This collective allows me to experiment with what is seemingly ordinary

#traindiaries is my visual diary, an equivalent of me coming home after commuting in the Mumbai local and scribbling in my journal. Katha Collective allows photographers like me to tell our life stories. The ladies’ second class coach is a space where everyone is inter-dependent. Over the years, I have seen deep relationships being forged here. I have watched sweaters knitted from start to finish, women groom themselves for work from scratch, and catch up on sleep. Full meals are prepared on the move, only short of the final tadka. This collective allows me to experiment with what is seemingly ordinary

- Anushree Fadnavis, photographer, whose photo essay, #traindiaries, is part of the Katha Collective

I’ve been a freelance photographer for seven years but joined Instagram just four days before the Katha Collective was launched. I am still new to it, and am amazed at the reach and scope of the medium. It is a breath of fresh air.

I’ve been a freelance photographer for seven years but joined Instagram just four days before the Katha Collective was launched. I am still new to it, and am amazed at the reach and scope of the medium. It is a breath of fresh air.

Initiatives such as Katha Collective raise the bar of experimentation — one has to be more spontaneous. The sheer volume of good work on Instagram is very inspiring. My upcoming series as part of the collective will be on the gaze of my istriwallah here in my colony at Noida. He has seen the neighbourhood change over decades and has ironed clothes of families over generations. I want to capture how he sees his surroundings change over time.

- Zishaan Latif, Noida-based photographer, whose photo essay, #istriwalla, will soon be featured on the Katha Collective

I will join the Katha Collective sometime in the coming months. Uploading Instagram images will be both exciting and daunting, because I bought my first smartphone only in January! I am still figuring out this new, fast Instagram-way of photography, having done it on 35 mm film and with DSLRs. For decades, I have been a reflective photographer, and like to let my photographs mature over time. However, a new grammar in photography emerges through initiatives such as the Katha Collective, and only those who can play with its language well will stand out. It is an intimidating prospect. My biggest challenge here will be to see whether Instagram pushes me to see things differently. Just like the 35mm film after plates changed war photography by making it more urgent, will Instagram open newer possibilities for someone who has been photographing Mumbai for decades? I am excited to find out whether it gives me more access, more accurate possibilities and, most of all, pushes my perspective.

I will join the Katha Collective sometime in the coming months. Uploading Instagram images will be both exciting and daunting, because I bought my first smartphone only in January! I am still figuring out this new, fast Instagram-way of photography, having done it on 35 mm film and with DSLRs. For decades, I have been a reflective photographer, and like to let my photographs mature over time. However, a new grammar in photography emerges through initiatives such as the Katha Collective, and only those who can play with its language well will stand out. It is an intimidating prospect. My biggest challenge here will be to see whether Instagram pushes me to see things differently. Just like the 35mm film after plates changed war photography by making it more urgent, will Instagram open newer possibilities for someone who has been photographing Mumbai for decades? I am excited to find out whether it gives me more access, more accurate possibilities and, most of all, pushes my perspective.

- Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Photo Editor, National Geographic Traveller India

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!