A new breed of cartographers, data activists and illustrators stretch the limits of the map, without shaking boundaries

ADVERTISEMENT

Could our random selfies — the many duck-faces and pouts we make — actually contribute to valuable data? We point, we shoot, we tag people and places, and then we post.

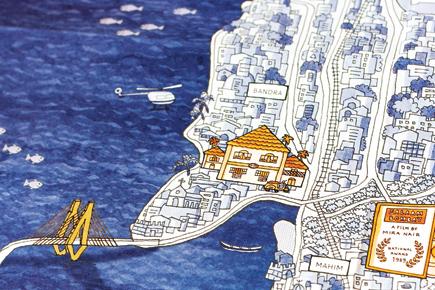

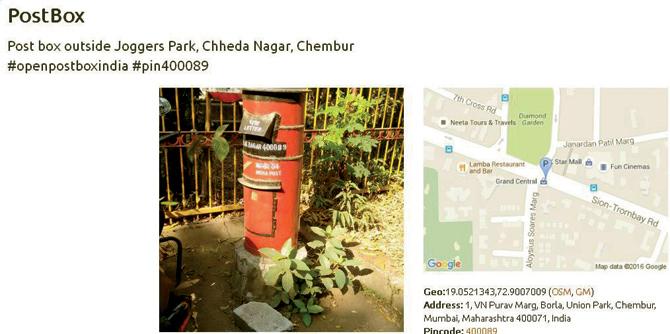

Personalising urban experiences is map-booklet City by the Sea by Kahani Designworks, run by principal designers Ruchita Madhok and Aditya Palsule

Ruchita Madhok

In April last year, mapping platform Mapbox’s Eric Fisher published the Geotaggers’ World Atlas, which pointed out the world’s most interesting neighbourhoods. The mammoth project, which was five years in the making, used locations of photos posted on picture sharing site, Flikr. The result: a web of well-travelled streets across the world, crowdsourced from unwitting Flikr contributors. It is ultra-digital but retains the flavour of people sketching on streetsides.

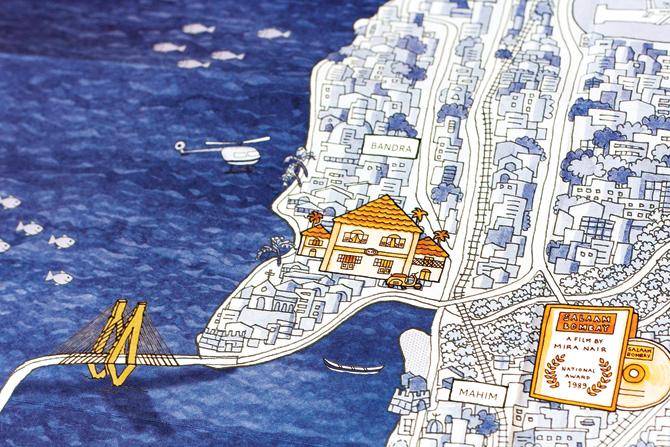

Gurgaon-based illustrator Urmimala Nag personalises the experiences of travel-writers to make her maps, replete with local culture and architecture

Urmimala Nag

On home turf, Mapbox’s data artists have been up to developing maps, stretching the limits of what cartographic tools can be used for. A map on gendered names of streets (which revealed that “between Bengaluru, Chennai, London, Mumbai, New Delhi, Paris and San Francisco, the percentage of streets named after women is an average 27.5”), for instance.

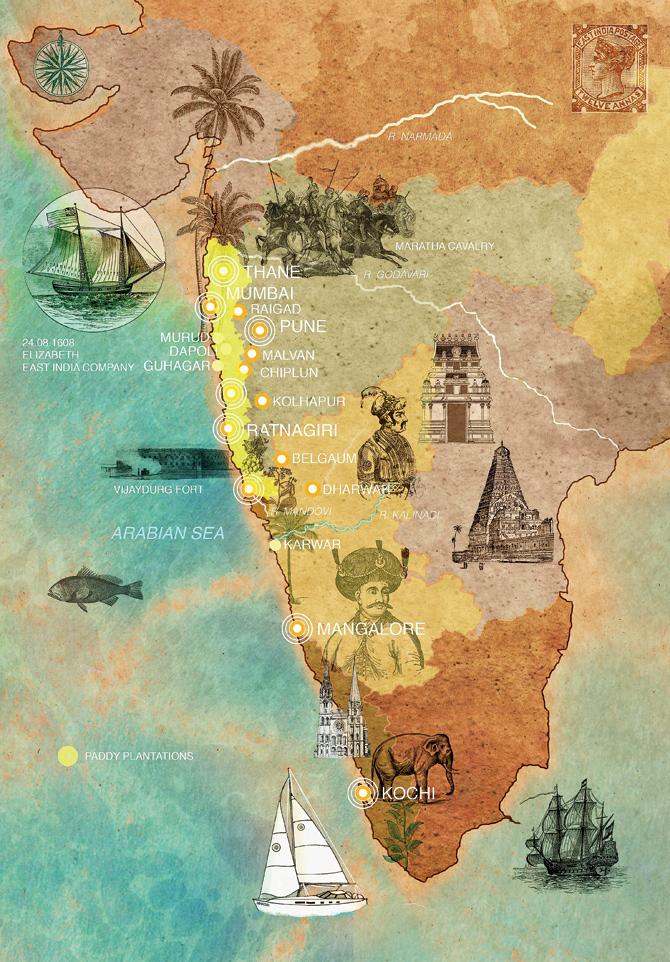

Thejesh GN, co-founder of DataMeet and contributor to OpenStreetMap, has geo-tagged postboxes across the country in a mapping project called OpenPostBox

Thejesh GN

It is no wonder then, that when the Ministry of Home introduced the draft Geospatial Information Regulation Bill 2016 last month, which regulated the dissemination and distribution of geospatial information, groups got together to resist it. Geo-Bangalore, DataMeet, DataKind and Open Data Bangalore came up with a campaign called Save the Map, where recommendations to the draft as well as its implications were discussed.

c responses to the Bill closed earlier this month, but the conversation surrounding it pointed out to a number of cartophiles across the country. Right from using digital tools to vintage appeal, maps in the hands of designers these days go beyond the prescribed, and delve into the personal, the alternative and even the fantastical, at times.

“At the moment, there seem to be a number of people in the country who are interested in mapping,” says Dr Chitra Venkataramani, anthropologist and Harvard post-doctoral fellow who delivered a talk this past week at the Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies on cartography and visual politics. “There is a long history in India of mapping, right from colonial times, and with new technology there comes a shift. It is no longer just governments who can use maps. Anyone, with access to tools and geospatial data, can claim mapping as a means of political engagement,” she says.

Opening up the streets

Take Gaurav Godhwani and Thejesh GN, both based in Bengaluru. Data activist Godhwani, 25, from the team behind Save the Map is involved with technological-led civic activism. He is an active contributor to volunteer-led mapping programme OpenStreetMap. On a recent trip to Sikkim, Godhwani, a mountain lover, updated details of Lachem, an unmapped area, to OpenStreetMap. Call this his hobby, which includes attending OpenStreetMap Bengaluru’s field trips and “mapping parties”. At these sessions, participants have mapped streetlights on Old Madras Road and trees in Bengaluru’s famed parks.

“The idea is to make data transparent and refrain from analysing it,” says Godhwani, who professionally works on geographical boundaries. The more transparent the data, the more obvious map-readers’ conclusions, is one way of looking at this. What’s the story of streetlights? Or that of trees in a city? Once you have the numbers and the visuals to understand them, you’ll figure.

“Mapping and maps overlap, and contribute to each other without us realising it. Mapping is a form of visualisation and making information accessible to the public. Imagine you receive an excel sheet full of information that could throw you off; but once you see these on a map, viewers are drawn to it,” says Thejesh GN, co-founder of DataMeet. Under the DataMeet umbrella, mapping meetups happen through Geo-BLR, an initiative by cartographer and programmer Sajjad Anwar. These mapping meetups have their chapters in other cities as well, and a look at mapping activity here ranges from the whimsical to the serious. Thejesh has set up OpenPostBox, a geo-tagged record of post-boxes, an endangered species, in the country. Anwar has made a floodmap of Chennai during its worst monsoon disaster last year, where people marked the most flooded areas.

These and other humanitarian mapping work are at risk with the Geospatial Information Regulation Bill. “Information and identity are powerful. Maps are a kind of identity; if a restaurant, or a slum, doesn’t exist on a map, that stands for something,” says Thejesh.

Making it personal

“Open-mapping is rooted in older histories of counter-mapping. These sort of mapping practices, suggest that the developmental vision of the state does not always capture the everyday experience of the city. Instead, counter- mapping pushes against these visions.” says Venkataramani.

Ruchita Madhok, founder and principal designer of Kahani Designworks, would agree since she has brought out two map booklets on Mumbai namely, Building Bombay and City by the Sea. The former took on public architectural heritage while the latter looked at the city’s relationship to the sea. Printed on handmade paper, Madhok intended these to be mementoes to the experience of the city, where one could add one’s own impression to it. “There has been a proliferation of map-making thanks to Google and 3G Internet, but we wanted to personalize the city, which is otherwise seen as a government space,” says Madhok.

Illustrator Urmimala Nag, based in Gurgaon, has made more than 70 maps, mainly working with watercolours, since 2012. Her work has been mainly related to travel-writing, and each map takes in a careful note of the locale’s people, biological wealth and culture. “I was looking at how people conceptualise themselves in relation to their environment, while offering a spatial and cultural perspective,” says Nag.

“Maps have stood the test of time and there is a possibility here to free maps from being considered mere scientific tools,” she continues. Now, who is game to draw a map?

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!