Home / Sunday-mid-day / / Article /

Canned it in 1957

Updated On: 22 May, 2022 07:52 AM IST | Mumbai | Nidhi Lodaya

With India chosen as the first country of honour at the 75th Cannes Film Festival this year, Sunday mid-day takes a trip down memory lane to the 10th Cannes Film Festival

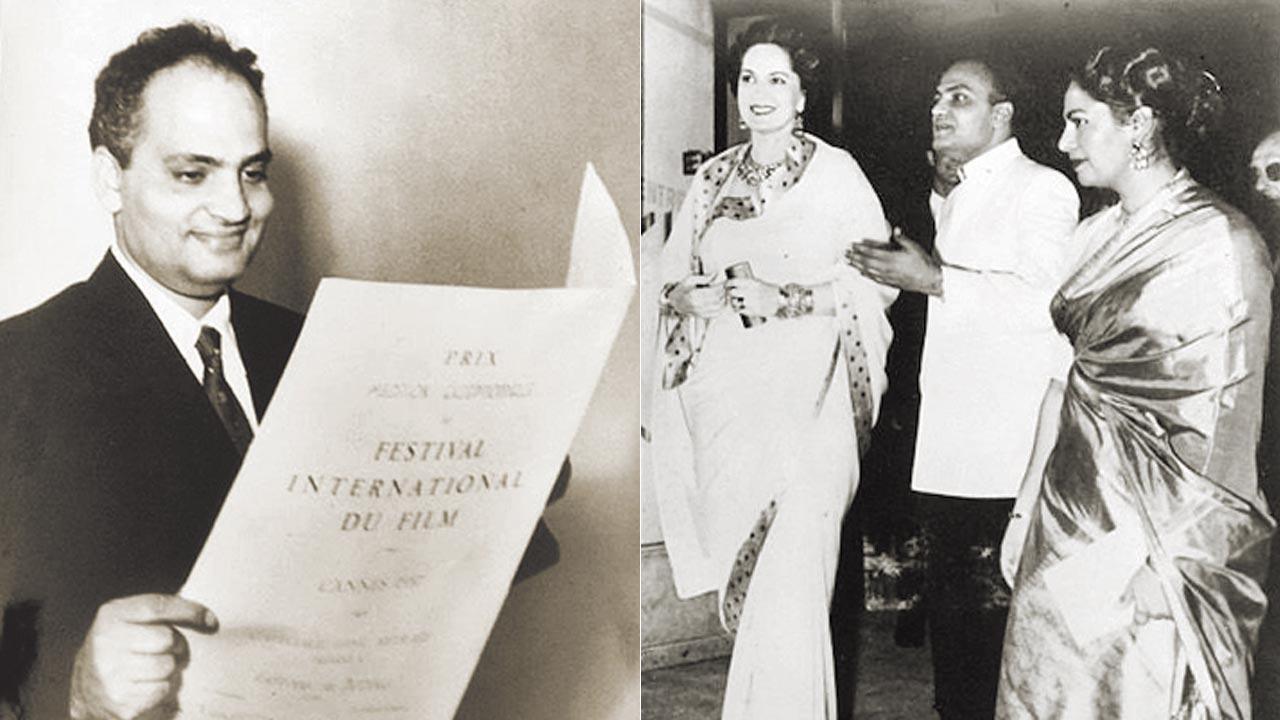

Filmmaker Rajbans Khanna won the award of the Best Director for his film Gotama The Buddha at the 10th Cannes Film festival in 1957; (right) Begum Agha Khan, mother of the present Agha Khan, with filmmaker Rajbans Khanna and wife Usha at the banquet hosted in Cannes, post the screening of his film

This year marks 65 years since Rajbans Khanna’s documentary film, Gotama The Buddha, won at the 10th Cannes Film Festival. Born in 1920 in Lahore, Khanna was one of the country’s well known political filmmakers. Sunday mid-day got in touch with Devieka Bhojwani, one of Khanna’s three children and a theatre actor, to talk about their father’s achievements and how he reached the Cannes in the mid-’50s.

Right after school, Khanna plunged into the freedom movement until India gained independence. Post-1947, he dedicated his efforts to Kashmir. “He was a student leader and also part of the militia that protected Kashmir, once he was out of college,” recalls Peddar road-based Bhojwani. The sense of pride in her tone is evident as she speaks about her late father’s political involvement. “He had never made a film before,” she says. “He was a writer, poet, revolutionary, student leader and leftist. He believed in fighting for the cause of national integration.” Khanna only moved to Mumbai after marrying Usha Khanna. His interaction with director Bimal Roy in Mumbai was sparked when he showed him the script for Gotama The Buddha.