A library in rural Satara with a 70-year-old legacy steeped in progressive, anti-caste values, continues to serve the local community. mid-day traces Hind Vachanalay’s radical origins and future plans to take its initiatives beyond home ground

The Hind Vachanalaya is a catalysing, unifying force in Rahimatpur, and city residents contribute to its sustenance through funds and books from their own homes. Pics/Sameer Markande

Across fields of marigold, sugarcane and paddy, Nikhil Nimbalkar travels 45 km from his Udtare village to Rahimatpur in Satara district. In this quiet city, home to humble two-floor houses and businesses, the Hind Vachanalaya and Granthalaya enjoys a towering presence. From the steps of its staircases to the signs on its walls, the public library is a celebration of reading and knowledge, and the ways in which they can open the doors of one’s mind. It was in a video circulating on YouTube that Nimbalkar noticed phrases like “Savay laavu vaachanaachi, ughadu daare pragatichi [Inculcate a reading habit, and watch the doors to progress open for you]”.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I came across the video a month ago. In my village, no one has ever suggested that a public library be established. It tends to be noisy all the time, and I’ve often had to find a spot in the nearby forest to study in silence before crucial exams,” Nimbalkar says to mid-day. He is the newest addition to the Hind Vachanalaya’s 1,610-strong membership comprising students, the elderly who take great leisure in reading newspapers together, young children and working adults.

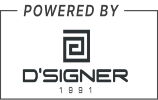

The shelves at the Hind Vachanalaya include titles from Ashatai and Anna Deshpande’s original collection, which they wished to share with fellow Rahimatpur residents

The shelves at the Hind Vachanalaya include titles from Ashatai and Anna Deshpande’s original collection, which they wished to share with fellow Rahimatpur residents

The library is living out its third life in this building which was meant to be part-gym, part-reading room. In the months before it opened in January 2022, former head of Rahimatpur’s municipal council Sunil Mane made a crucial decision: The Hind Vachanalaya will take forward the vision with which it was set up in 1952 by Ashatai Deshpande, a woman who married into the city and transformed its reading culture after observing that there were no libraries or public reading rooms in sight.

It is the name of Ashatai’s husband, PN ‘Anna’ Deshpande, writ across a gate that welcomes us into Rahimatpur. Anna, a key player in the local freedom struggle, was also a doctor who worked out of the ground floor of the Deshpandes’ home. Ashatai’s efforts turned the floor above it into an inclusive library, welcoming all of the city’s residents—across caste and class lines. The Deshpandes were known in the area for their progressive values, as they strongly opposed social norms like dowry. mid-day travelled to Rahimatpur to find that 72 years on, Ashatai’s legacy perseveres as the Hind Vachanalaya—held up by the very community it serves—adapts to modern concerns and serves villages near and far away.

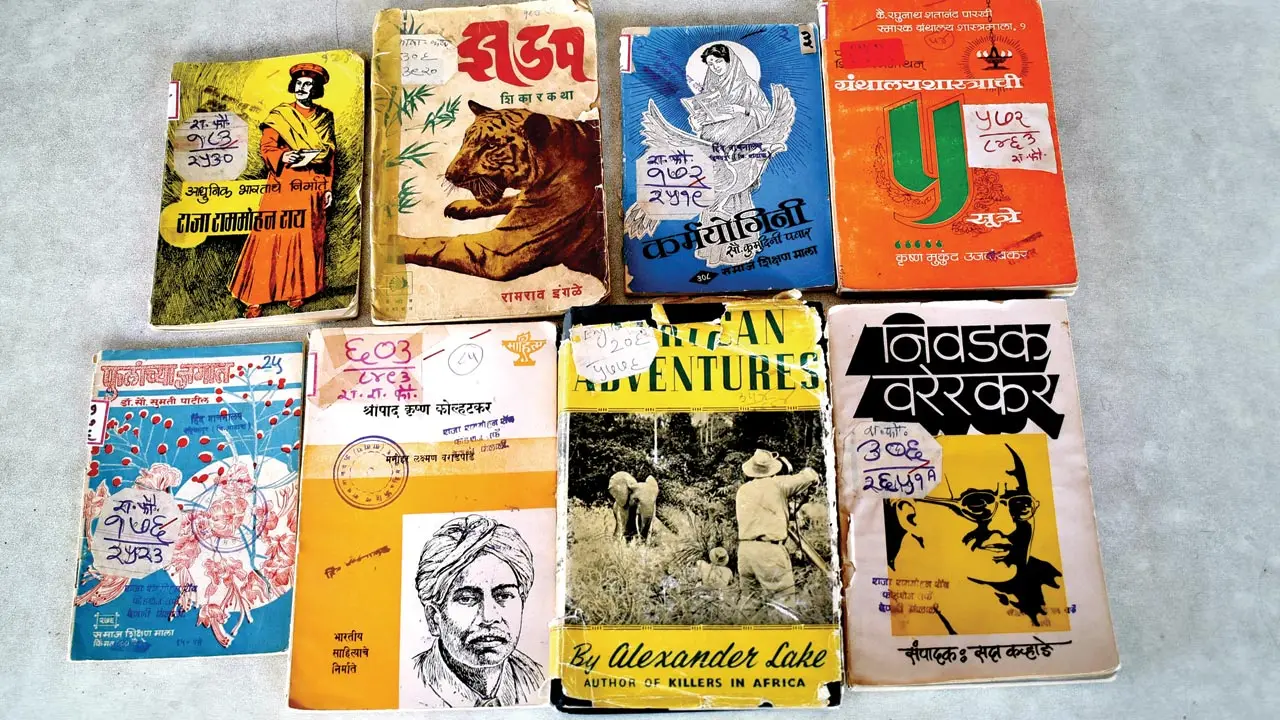

The beehive-shaped desks and access to WiFi gives local students access to resources that they did not have in their native villages

The beehive-shaped desks and access to WiFi gives local students access to resources that they did not have in their native villages

Even as she lives and works in faraway Delhi, Dr Ashwini Deshpande can distinctly recall the many hot summer afternoons she spent in Rahimatpur, at her grandparents’ busy home. It was akin to a traditional wada with a central open courtyard and rooms on all sides. “My abiding memory is a peculiar mix of smells: of medicines that my grandfather mixed and dispensed to his patients, intermixed with the smell of leather binding and printer ink from the library. A very odd mixture that I can still smell. It spells love and home for me,” Dr Deshpande, a professor of economics and founder of the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis at Ashoka University, says.

Ashatai was all of 4’10”—a diminutive woman—but the shadow she cast was contrastingly long. “She was highly educated, culturally accomplished in music and dance, and progressive for her time. Actually, her thoughts and actions would be progressive even by today’s standards. She was soft spoken, with a ready smile, and a gift for elegant writing,” Dr Deshpande recounts.

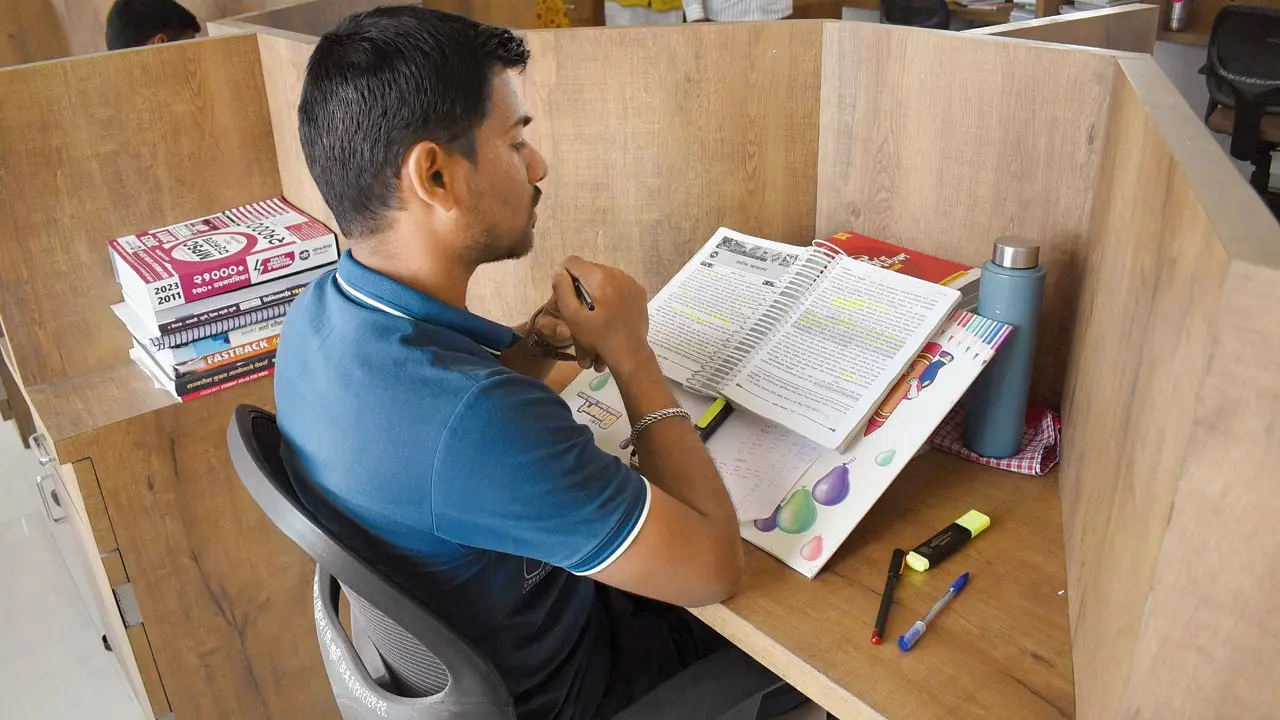

Sunil Mane, Hind Vachanalaya trustee and local politician

Sunil Mane, Hind Vachanalaya trustee and local politician

Bakul Deshpande-Vaidya, a Japanese language teacher and the economist’s cousin, says that Ashatai was keen to establish the Hind Vachanalaya so that others in the village could have access to the books in her and her husband’s collection. “This collection included titles like Jayant Dalvi’s Chakra, Durga Bhagwat’s Rutuchakra, as well as plays like CT Khanolkar’s Ganuraya Ani Chani and English novels,” she says, “The library’s doors would open at 8 am, and we could easily expect at least 25 people to visit each day.” Come 2024, and an average of 100 people step into the institution’s premises daily.

Dr Deshpande has vivid memories of accompanying her grandmother on her canvassing trips across the area, where they would often approach those who lived on the margins, in impoverished homes. Here, Ashatai was never one to be denied, nor would she refuse the water or food offered to her. “Some of my earliest memories—I must have been six or seven—are of walking with her to all parts of Rahimatpur, including to the margins. I would ask where we are going and she would say, ‘To get women and children to come and read in the library’. On the days we went far, I would get tired and ask, ‘Is this still Rahimatpur?’ And she would say, ‘Yes, this is also Rahimatpur’.”

Uma Sawant, assistant librarian; (right) Sanjay Jangam, librarian

Uma Sawant, assistant librarian; (right) Sanjay Jangam, librarian

She had the deepest impact on her children and their children, who we know today as thespian Sudhanva Deshpande and actress Amruta Subhash. “I first realised how towering her persona was when I witnessed the multitude of people that showed up after her death... The significance of her thoughts and personality became apparent to me in bits and pieces when I started working on caste and gender inequality in my early 30s. I deeply regret that I never got a chance to talk to her about her unusual personality and life choices. When she was alive, I could sense she was out of the ordinary, but couldn’t quite tell how or why,” Dr Deshpande shares.

To the extended Deshpande family, the Hind Vachanalay as it stands today is a matter of pride. “It feels absolutely amazing. She would have been so proud to see her vision vindicated,” the economist says with elation.

The trustees and staff of the Hind Vachanalaya; the latter work 12-hour shifts to keep the library running

The trustees and staff of the Hind Vachanalaya; the latter work 12-hour shifts to keep the library running

"Libraries in big cities like Pune and Kolhapur tend to be crowded. They also don’t make provisions for students to eat within the premises, which is a challenge if you want to spend all day studying,” says Aakash Shitole, 24, who is preparing for government service exams. A Rahimatpur resident, he was part of the Hind Vachanalay’s first cohort of members and recalls those initial days when readers were asked to wholeheartedly embrace the library while the fees were still being fixed. Today, the price of membership for the elderly is Rs 205, while that for students is Rs 700.

Each section of the library is brimming with activity, and there’s not a seat left empty. On one floor, where male and female readers can sit separately, they form small groups to study together. On another, beehive-shaped study desks allow about 30 students to focus on test prep, write out notes and flip through expansive study material. On the top-most floor, they have access to computers and WiFi. “For many readers, this is a first. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they became accustomed to taking online lessons on their phones—often the only gadgets in their households,” says Mane, who is a trustee of the library.

The elders in the community visit the library everyday to read newspapers and discuss current affairs

The elders in the community visit the library everyday to read newspapers and discuss current affairs

The initial hurdle in transferring the library’s location from a rental space to the current building was the lack of funds, Mane explains (it was moved out of the Deshpande home after its first 50 years). Over time, he won the confidence of the municipal council, and presently, the library is funded by the municipality, its own trust, as well as donors—individuals and organisations like the Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation. The Hind Vachanalaya’s revamped, expanded existence has given a new meaning to the lives of its core staff members—librarian Sanjay Jangam and his assistant Uma Sawant—who work 12-hour days. For Sawant, 27, who has a bachelor’s degree in electronic engineering, it is an opportunity to pursue a career in a discipline she loves rather than one that was a conventional, “safe” choice.

In the early hours of the evening, the proud parent of a boy from the area, who earned a seat in IIT-Gandhinagar, visited the library to donate books his son used to prepare for the Joint Entrance Exam. These donated books occupy shelves alongside those purchased by the library itself, based on students’ and readers’ requests. “Individual titles required to prepare for entrance exams tend to be quite expensive. When a library like this one purchases them, they can be used by many batches and generations of students,” says Sapna Nanawre, who stood first in her MBA course at a Satara college. She comes from a family traditionally engaged in agriculture in Borgaon village, nearly five hours away.

Rahimatpur’s quiet spirit comes alive thanks to the library, which attracts readers from nearby towns and villages

Rahimatpur’s quiet spirit comes alive thanks to the library, which attracts readers from nearby towns and villages

“When I get bored or tired of studying, it’s nice to flip through the fiction section here. I’m also drawn to autobiographies of women,” the 23-year-old adds. Certain bookshelves also contain titles from Ashatai’s time, like a copy of Jagjeta Roboor, a Marathi translation of Jules Vernes’ Master of the World. The institution’s collection also features rare and old versions of epics and commentary like the Mahabharata and Dnyaneshwari.

The library’s records include mentions of past members who have aced entrance exams, and who are felicitated upon their return to Rahimatpur. Mane says that he and the other trustees envisioned that the institution would nurture minds who did well at exams like the UPSC. He recalls that there was a point when the Trust considered calling it an ‘abhyasalaya’ instead of a library and reading room, given the growing demand for academic books and a space where students could read and research in peace. “I felt that making it an abhyasalaya would narrow its scope and goals. There’s much more to reading than just academics. What PUCs are to vehicles and air pollution, reading and books are to illiteracy, bias and social ignorance,” he says.

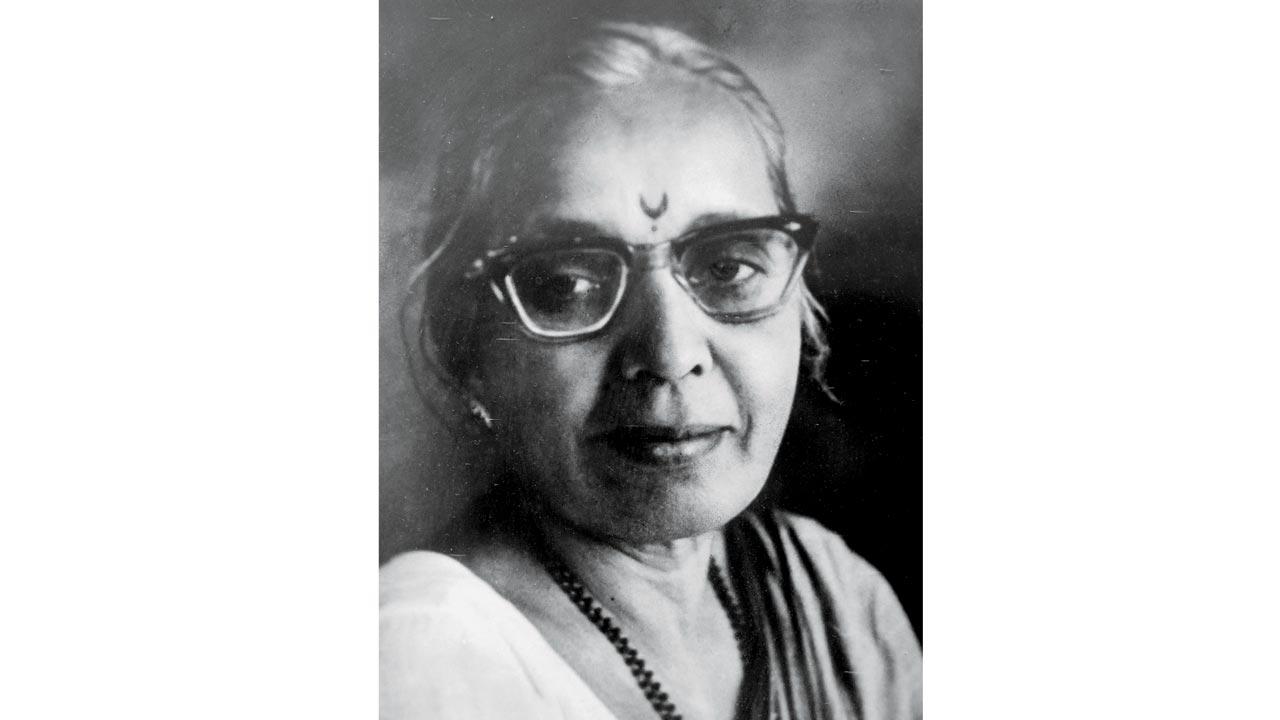

Ashatai Deshpande urged women and children, especially those who lived on Rahimatpur’s margins, to visit and use the Hind Vachanalaya

Ashatai Deshpande urged women and children, especially those who lived on Rahimatpur’s margins, to visit and use the Hind Vachanalaya

Perhaps the one segment of the city’s population that remains conspicuous in its absence is married women and mothers. “They are members of the library; it’s just that they send their children here to issue books in their name and return the titles they’ve read. Between housework and caring for children, they carve out time to read,” says assistant librarian Sawant. As one peels away at the layers of Rahimatpur’s history, what emerges is a nourished literary tradition—one that defines the area’s social ethos even in present times. One section of the library features the engraved faces of father-son duo Shankar and Vasant Kanetkar, a poet and playwright-novelist respectively, who called the city their home and were active in the 20th century.

The Hind Vachanalaya’s significance in Rahimatpur is best evidenced by the ways in which it goes far beyond its mandate, whether it is in facilitating foreign language classes for its members, or holding community-oriented programmes for farmers. Some of the Japanese lessons were given by Deshpande-Vaidya, who wished to give back to the city and build on her grandmother and father’s legacies; the latter donated his books to the library and served on its managing committee in the past.

Next on the horizon is a travelling library, housed in a small vehicle. “We hope that this dynamic library can take a portion of the book collection to five villages on each day of the week, in the 40-odd clutch of villages that make up our khed. We’ve also found ways to incentivise new readers to take to reading, by honouring those who set new records for themselves,” Mane says, as he signs off.

1,610

Total membership of Hind Vachanalaya as of Jan 2023

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!