Home / Sunday-mid-day / / Article /

‘He was an undoubtedly complicated person’

Updated On: 03 March, 2024 08:00 AM IST | Mumbai | Neerja Deodhar

Through a new exhibit in the city, Himansu Rai’s grandson continues to trace the cinema veteran’s journeys, and his own roots. And it all started with a picture he found in the attic at 30

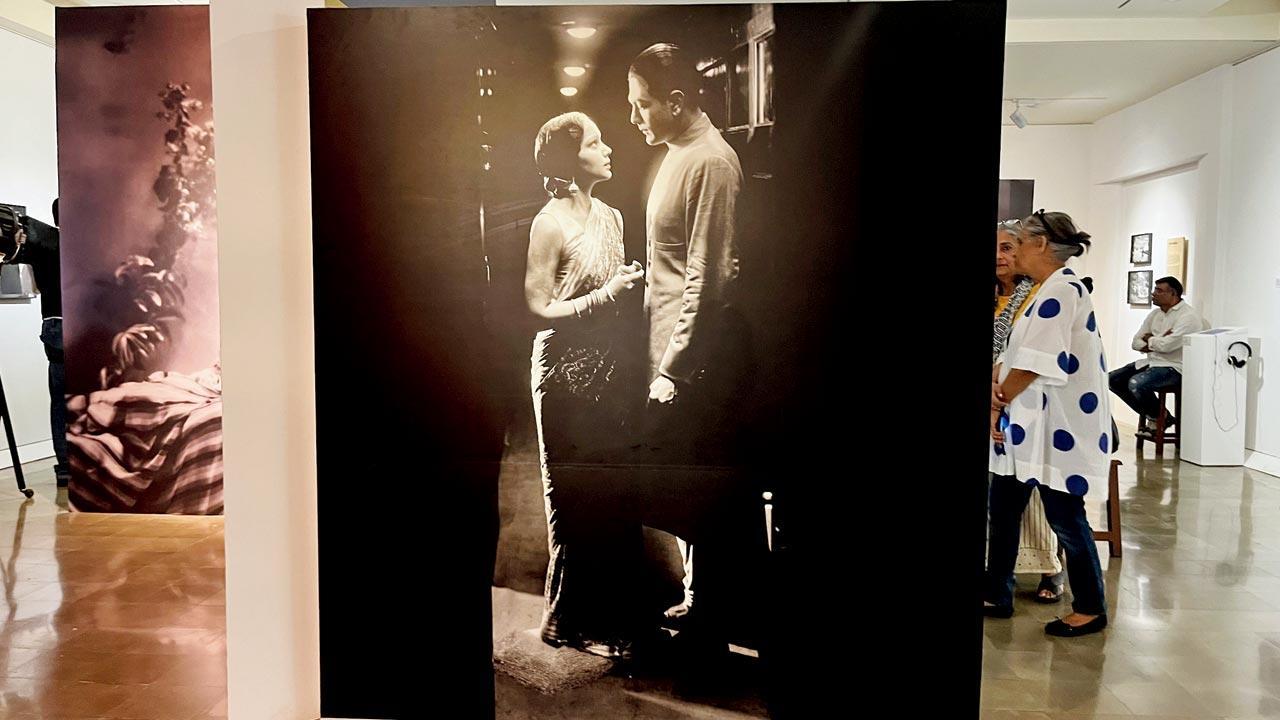

A Cinematic Imagination at the JNAF gallery is a tribute to Josef Wirsching, a cinematographer and still photographer who worked at Bombay Talkies. Pics/Atul Kamble

It`s no ordinary day at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya. The newly-opened, ambitious exhibition, titled A Cinematic Imagination: Josef Wirsching and the Bombay Talkies, has turned the walls of its Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation gallery into an arena where Devika Rani, a luminous screen presence and the biggest star of the 1930s, has come to life. In two stills placed side by side, she looks coy and naughty respectively, her eyes transfixed on the viewer’s own. A relative of the Tagores and the face of box office hits like Achhut Kanya and Izzat, Rani is also remembered for her marriage to director Himansu Rai, with whom she ran the pioneering Bombay Talkies studio.

Peering closely at a cutout of the actress is Peter Dietze, a Melbourne-based visual artist. Does he think Rani and his grandmother, Mary Hainlin, knew each other? “Absolutely—of course they did. There are pictures of Mary, my mother and Himansu together, one of which is on display here. It was a crazy time in the Roaring Twenties,” Dietze remarks.