Home / Sunday-mid-day / / Article /

How filmmaker Yousuf Saeed has been documenting qawwali of Bombay cinema

Updated On: 07 May, 2023 10:19 AM IST | Mumbai | Sucheta Chakraborty

A filmmaker’s decade-long research into the qawwali of Bombay cinema has resulted in rich documentation while opening up new avenues for studying India’s vast cinematic history

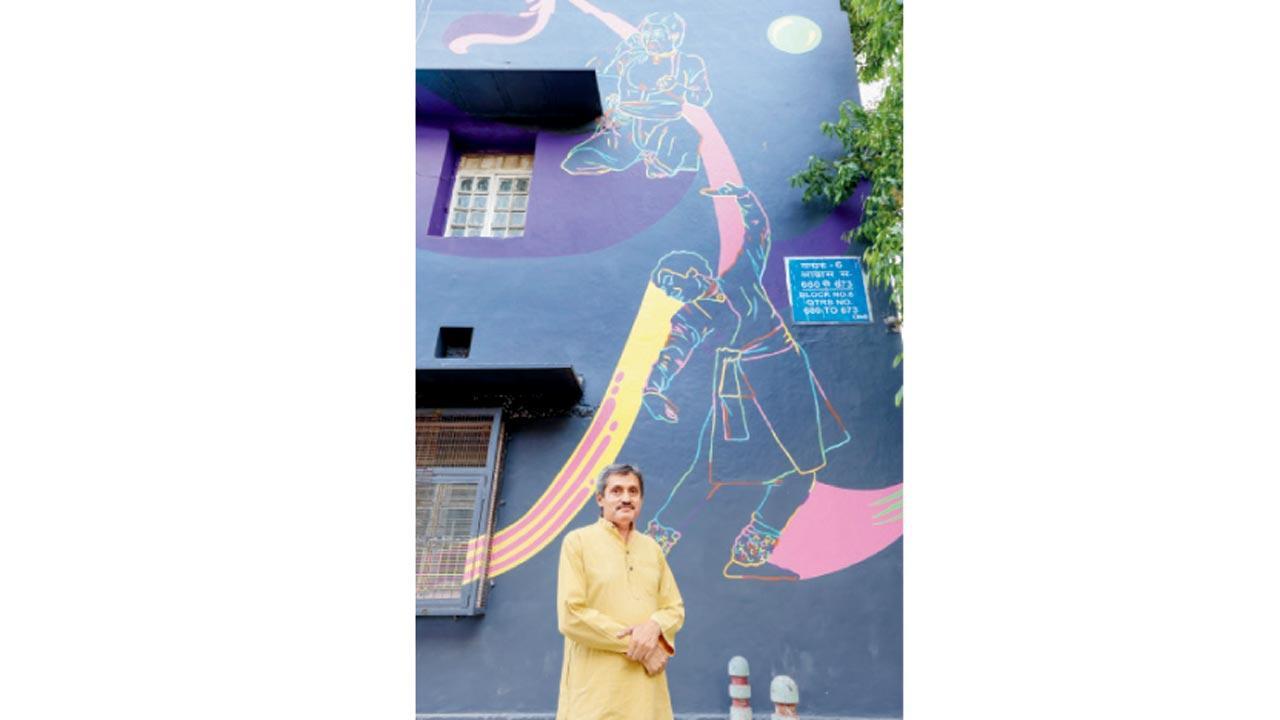

Yousuf Saeed’s Cinema Qawwali Archive has catalogued over 600 songs from Hindi films dating from 1939 to 2022. Pic/Nishad Alam

When people think of qawwali, they think of devotional music. But, the Mumbai film industry has given the qawwali a new identity, expanding its scope from Sufism to a song of entertainment in a secular, non-Islamic mode,” says filmmaker and researcher Yousuf Saeed over the phone from Delhi, where he is based. Saeed has made a series of films on Sufi poet and composer Amir Khusrau, who was credited with creating the qawwali in the late 13th century for Doordarshan. He has been documenting qawwali performances in various Sufi shrines for long, making him just the right man to create a database of more than 600 songs dating from 1939 to 2022. Since 2021, Bengaluru’s India Foundation for the Arts has supported this research that is now called the Cinema Qawwali Archive.

While there are no historical sources to indicate how the qawwali was performed before the recorded performances of the early 20th century, the time period of the recordings coincides with its performances in cinema. “It’s difficult to separate the histories of the cinema qawwali and the dargah qawwali because they appear alongside throughout the 20th century,” he says. “Even Khusrau was writing ghazals that were being performed in the king’s court as well as in the Sufi space of Nizamuddin Auliya.”