With France telling firms not to force employees to be enthusiastic, Sunday mid-day makes a case for keeping it effective and strictly professional

People who are “no fun” at work avoid office activities and events such as birthday parties, team lunches and often keep their conversation professional. Illustration/Uday Mohite

Aman Bathla’s personality at work is in complete contrast with how he behaves otherwise. The 28-year-old leading retail expansions is a DJ by night. He is “fun and spontaneous in general” but not in work mode. “It’s like living a split personality,” says the Khar resident, “a different version during the day and another at night.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Thankfully, Bathla’s company is not like the Paris-based management-consulting firm Cubik Partners, which fired Monsieur T. “for not being fun” at work. In 2015, the French man sued his former employer for wrongful termination. In response, France’s highest court said companies cannot force employees to participate in office parties and other supposedly enjoyable activities. A rightfully “no fun” person can also be excused from being a sport with colleagues, sharing details about personal lives, declining social plans. S/he can exercise the right to just come to office, work and leave. But does being cordial and professional help you climb the ladder?

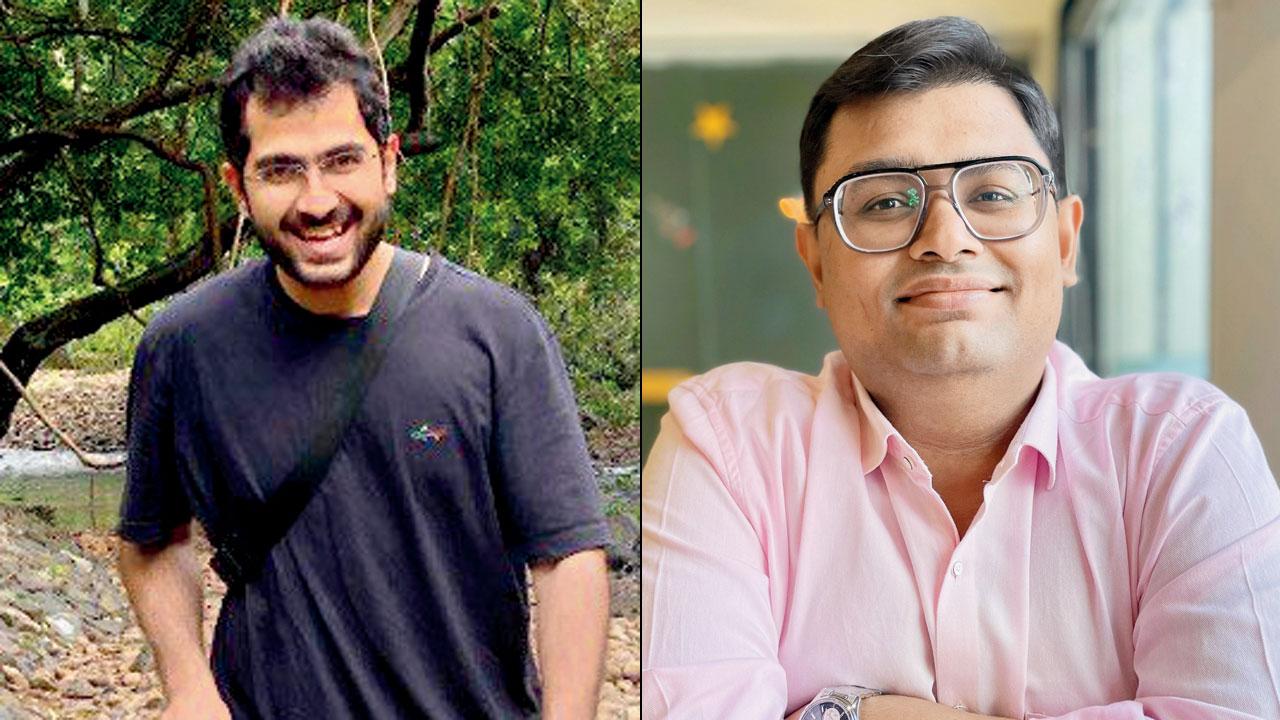

Daljeet Arora, Piyush Bharti and Ajith MS

“I feel it’s transactional at the end of the day,” says Bathla. “I am purposely not interacting with people; I don’t want to speak beyond what is necessary.” Nirav Mehta, a Ghatkopar-based enterprise account manager at a startup, feels the same way. He has flexible hours, and when in office, he heads straight to his desk, finishes the job, and leaves. In his family business, he often saw the lines between personal and professional lives blur when it was led by his father and grandfather. So when he took over, he ensured that the lines were strictly drawn. He maintains this in the startup too. “It’s just something I cannot compromise on,” says Mehta. “I rather get work done and head home to be with my family, meet friends, catch up on hobbies, especially reading, and take some time off to work on my

mental health.”

Roughly 15 people work with Mehta, and his Lakshman Rekha has worked to his advantage. He doesn’t take “long smoke breaks” and dodges personal questions with diplomacy. However, Mehta has lunch with his colleagues. But even during those 30 minutes, the conversation never veers to the personal. “By not being that fun person, colleagues actually respect the time they spend with me,” he says.

Unlike Mehta, Bathla doesn’t even have lunch with his colleagues. “Few colleagues ask ‘why am I so moody and quiet’. I don’t have an appropriate answer for them,” he says. In fact, he is the kind of person who refrains from adding his peers on his personal social media. Does the fear of missing out not nag them? “Quite the opposite, I don’t feel a sense of belonging,” says Bathla. Even Mehta would rather catch up on sleep than “go out for drinks” with colleagues.

Aman Bathla and Nirav Mehta

The drawing of personal boundaries can be seen in the field of education as well. Daljeet Arora, who works in a school, avoids staff birthday parties and other post-work fun activities spun for the teaching staff. “I’m a workaholic,” she states, and plainly excuses herself saying she’d rather go home. She believes cultivating closeness towards colleagues can work against her. “When you share a personal issue, it is bound to reach other people in the workspace, and that really affects one’s mindset,” says Arora. The primary school teacher empathises with the personal life situations of her colleagues, but excuses herself from such conversations so that it doesn’t affect her work.

But not everyone has the privilege of being able to refuse. A Delhi-based journalist shares how her company would have mandatory movie nights for staff, and anyone who failed to show up would get a salary cut.

We wish she knew that was illegal. “This is wrong,” says Piyush Bharti, CEO and founder of human resource consulting firm Radtalent. “Any staff activity has to happen during the office hours. You cannot set up a lunch or an event on non-working days or non-office hours, and expect people to show up. Unless, it’s a staff off-site or picnic, but even then, the company must check the availability of maximum employees and cannot force them to go.” Bharti is aware that the need for such activities is being questioned, post pandemic, but says, “The reason we have these events is because they are considered team-building activities by HR. Also, due to multiple lockdowns, many colleagues have not had the opportunity to get to know each other. This is a perfect excuse.” He also believes that since people spend more time in office than at home, creating a pleasant and friendly atmosphere is HR’s goal.

Besides plain absence of desire to attend an office party, some employees are shy and reluctant to do certain activities in front of colleagues. Bengaluru-based engagement analyst at an MNC, Ajith MS, recognised that some people have genuine social anxiety. His company, which has a community of about 10,000 people, held its award ceremony in the metaverse, instead of in-person or virtually.

“Metaverse bought a new perspective for introverts, and it was inclusive as well,” he says, adding that more people showed up. “An informal and personal tone increases the sense of community and belonging. It builds a better bond,” he says.

We could write these off as personal quirks, but science has the last word. A study conducted by the University of Sydney last May—titled Collecting experimental network data from interventions on critical links in workplace networks—revealed many employees were okay with anti-socialness. “Many workers told us that they despise team-building activities and see them as a waste of time,” said lead researcher Dr Petr Matous in a news release.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!