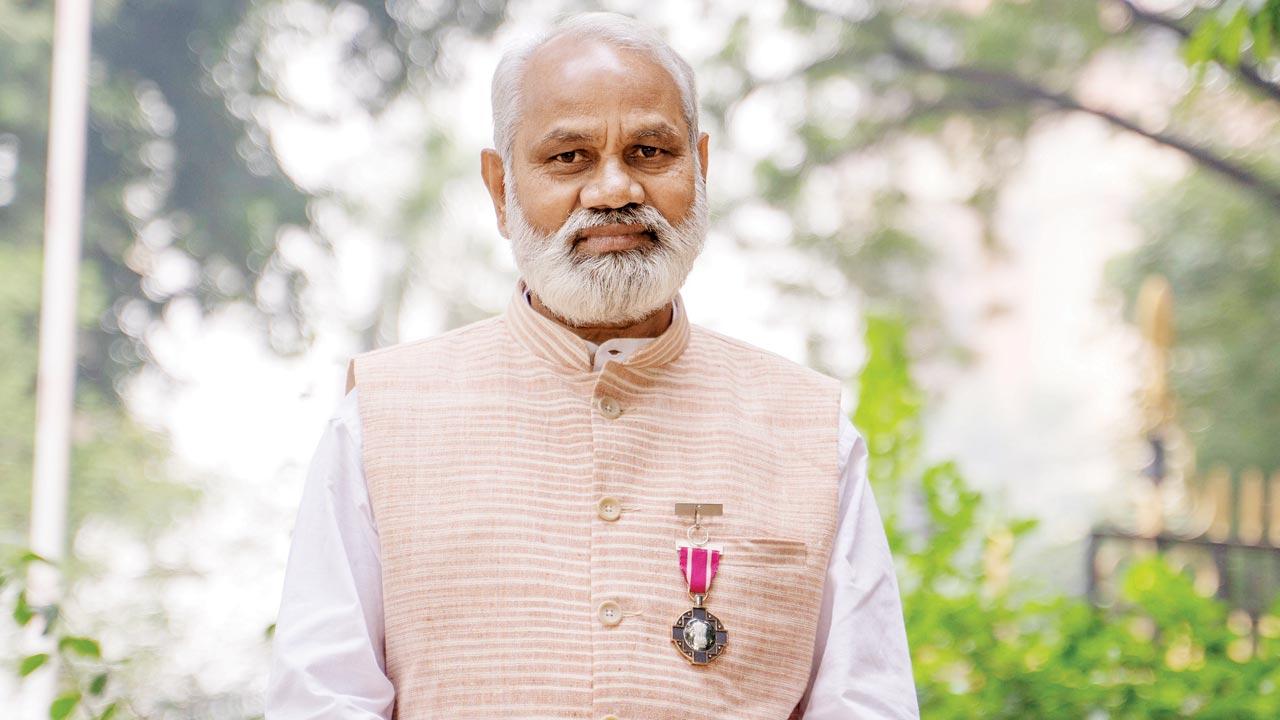

With puppeteer and Chitrakathi artist Parshuram Atmaram Gangavane being awarded the Padma Shri, an art form of a tribal community in Maharashtra has gained visibility and recognition

Gangavane performing with his sons Eknath and Chetan

Sixty-six-year-old Parshuram Atmaram Gangavane remembers his earliest Chitrakathi performances at the temples of the village of Pinguli in the Kudal taluka of Maharashtra’s Sindhudurg district. Back then, he says, the same sheets of paintings were used for all performances, after which they were stowed away. Nearly 40 years ago, he thought of making new paintings, in an effort to make visible an art form that has been in his family for generations. His Padma Shri this week is a culmination of all those years of dedication to the craft. “I feel ecstatic that the art that generations of my family have kept alive has been recognised in this way,” Gangavane, who is presently in Delhi to receive the award, tells mid-day. “I began with an ambition and had I not, I wouldn’t have been able to introduce so many others to it today. People in my village too now realise the importance of keeping it alive.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The word Chitrakathi combines ‘chitra’ meaning painting and ‘kathi’, meaning story, the art form practised by members of the Thakar tribal community who were itinerant storytellers. A narrator would relate in Marathi episodes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata with the help of stylised paintings or shadow or stringed puppets and folk songs, and was accompanied by three instruments, which were the veena, the taal (a pair of clash cymbals) and the huduk—a two-headed small drum, similar to the damru. It is said that many of the original performers of the form were spies operating during the reign of the Maratha kings who were tasked with extracting information as they travelled through villages.

While originally performative in nature, Gangavane has shifted Chitrakathi’s focus towards handiwork. Pic/Nishad Alam

While originally performative in nature, Gangavane has shifted Chitrakathi’s focus towards handiwork. Pic/Nishad Alam

In 2006, Gangavane started the Thakar Adivasi Kala Angan (Museum and Art Gallery) as a way of popularising the art, the museum over the years attracting tourists and fine art students from cities like Mumbai and Pune who travelled to Sindhudurg to work on projects on the art form. He says over the years, he has received letters from the government asking for the Chitrakathi paintings and puppets that has been in his family for close to 400 years, but has refused to give them up. The Thakars, says Gangavane’s son Chetan, have traditionally practised 11 different performative arts of which Kalsutri Bahulya (string marionette), the Dayati (shadow puppetry), Chitrakathi and Pangul Bael, a ritual form of theatre around the figure of the sacred bull of Lord Shiva, are a few. “Although, traditionally, all of these fall under the performance arts, my father realised that Chitrakathi can also be promoted as a handicraft where we can make paintings and sell them. He used the performance art to promote craftwork, thereby shifting the art’s emphasis from performance to handiwork, and reintroducing it as such to people,” says Chetan, who along with his brother Eknath has taken the baton from their father. In recent years, they have also learnt to customise the tales they depict, creating, for instance, paintings on social distancing and COVID-19 warriors during the pandemic. Moreover, he says that they started promoting the art as ‘Pinguli Chitrakathi’ after the village, as they travelled all over the country to conduct exhibitions, workshops and seminars. “It was a tribute to the artisans who practice this art form, so that along with the art, the name of the village too reached people.”

In the last two years of the pandemic, with artisans out of work, the brothers also started online Chitrakathi workshops with their father, teaching people about the craft and discussing its history and association with the community, along with virtual tours of the museum and string and shadow puppetry shows, conducting them for organisations around the country.

Gangavane, who is elated after the reception at Rashtrapati Bhavan, now hopes to expand the activities of the museum which he started 15 years ago in a small cowshed. But he also feels relieved. “I have passed on this art to my sons, and even my grandson has now taken it up. Had I not done anything, Chitrakathi would have simply died out.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!