An architect and his team, spurred by the idea of affordable housing, traversed through the slums and chawls of the city to rediscover the byelaws governing our built heritage

Relaxation of building regulations in the Project Affected Persons townships have led to unhealthy space between buildings, and reduced light and ventilation in the homes. Pic courtesy/Sunil Thakkar and Philippe Calia

While almost every aspect of our life is regulated and governed by laws, we probably don’t think about how or why these rules came into being. For architect Sameep Padora and his team at sPare, a research initiative that looks at issues of urbanisation in India, it was a particular housing project that took them down a rabbit hole to delve into the history and creation of the city’s codes and byelaws for building homes. Today, this research has been documented and displayed at Ballard Estate’s new multidisciplinary hub, IF:BE, showcasing a range of images, diagrams and 3D models of buildings that have stood for over a century in the city. “It’s almost like an archaeological project. When we put each model together, we also tried to find out what was particularly specific to that project, and the unique details we could learn from it,” he tells this writer.

ADVERTISEMENT

The idea for the project came about in 2015, when a developer approached Padora and his team for an affordable housing project in Karjat. “That’s when we began our research to see how we could design these types of houses. We knew Mumbai is home to residents living in smaller homes for many generations. We were interested in finding out how they lived—what were the adaptations they made to their spaces and how [those have] fared over time. While we heard lots of narratives and stories from each home, we uncovered very little about the architectural quality or the tectonics of what comprises affordable housing.”

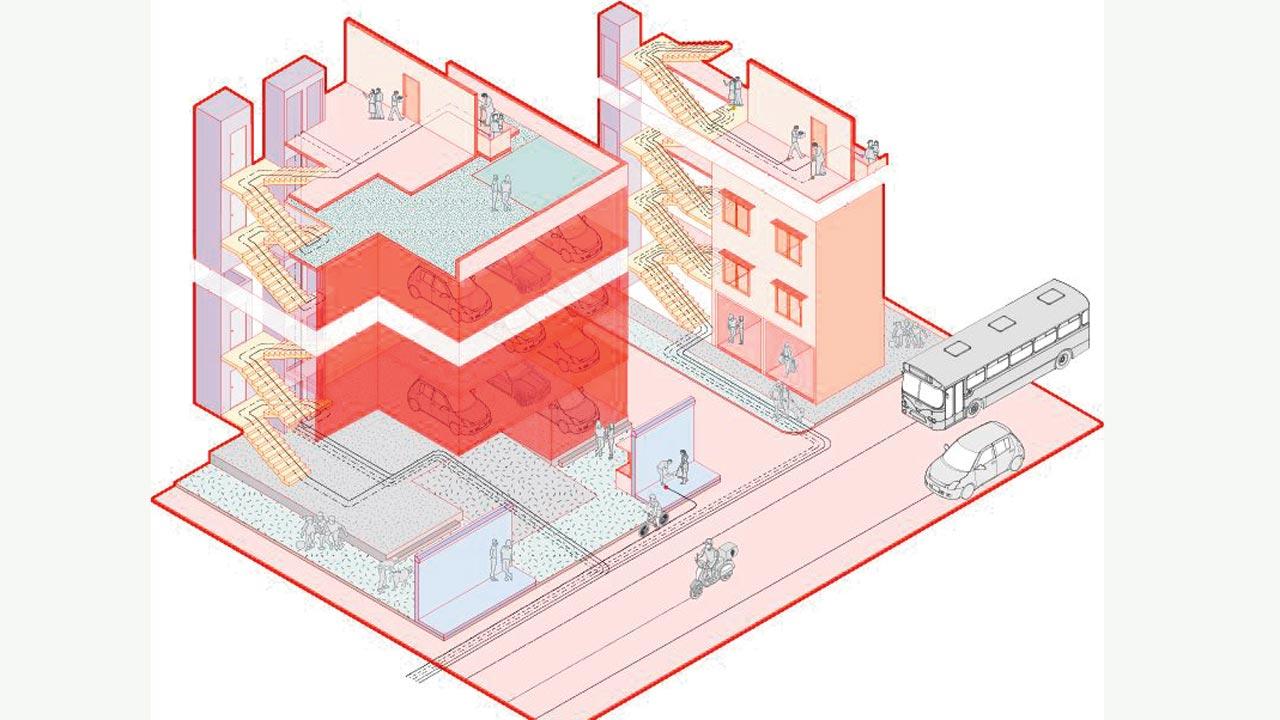

This illustration highlights how a boundary wall between a street and a building where the first few floors are assigned for parking, renders the street dead and unsafe. Courtesy/Team Spare

This illustration highlights how a boundary wall between a street and a building where the first few floors are assigned for parking, renders the street dead and unsafe. Courtesy/Team Spare

The first phase of the research saw them studying all types of small houses in the city, including chawls, wadas, and Slum Rehabilitation Authority and MHADA projects. These were compared across criteria ranging from circulation and ventilation space to room for socialising and leisure. “We started looking into the history of building codes in Mumbai, which took us to 1896, where the first codes were formulated during the plague,” he recalls. The exhibition begins with this historic event, exploring how it was instrumental in changing the urban form and geography of Mumbai. The primary motivation at the time was to create better light and ventilation for people within their homes, since data revealed that the plague spread between compact spaces and unsanitary living conditions. “From this origin point, we started following the rules that were populated around it. Coincidentally, in 2018, IIT Bombay and an NGO called Doctors For You studied settlements built by the state, where buildings stood as close as 10 feet apart from each other. Every fifth member in these colonies suffered from tuberculosis or some other respiratory illness. Their report attributed this to the nature of the architecture and lack of lighting and ventilation in the space. In a sense, the byelaws have allowed these structures to be built. This brings us back to square one because the first laws were to improve these conditions, while the current ones enable the spread of disease.”

During his research Padora discovered how distances between buildings were mandated. “The Bombay Improvement Trust [BIT] enforced a law stating that the angle formed between the base of one building and the top of the building next to it should not be more than 63.5 degrees. If the buildings were closer [or if the angle was higher] the homes wouldn’t get enough light and ventilation within. This was replicated from Glasgow, where the angle enforced is 45 degrees because they’re further up from the tropics.”

Sameep Padora

Sameep Padora

Padora says they’ve highlighted architectural differences a common citizen would sense and notice. “For example, in Dadar Parsi Colony, there were regulations written, stating [that] a boundary wall can only be solid till four feet, after which it has to be porous. This lets people look out and brings about a sense of safety for someone walking on the street. However, these days, the first few floors of a building comprise parking after which habitation begins. Since no programme opens out into the street, it renders it dead and unsafe. So you’ll sense the difference walking on the streets at night in old neighbourhoods in South Bombay or Dadar Parsi Colony compared to newer developments in Khar or Lokhandwala.”

One of the arguments this research opens is that Mumbai creates the infrastructure it needs. There are certain dwellings that exist here that cannot be explained through development plans, such as night shelter for children created in a space under the foot over-bridge at Marine Lines. It doesn’t show up in any architectural plans, yet it exists because the city needs it. Similarly, in Dadar, a person owns a shop where he sells his wares in the day and has made a home behind the hoarding above it. “Our next step is to study these anomalies to see if they indicate a means to look at development through the lens that isn’t a Western planning model, but instead reactive to what already exists on ground.”

Perhaps, the most symbolic for the common citizen is the last section of the exhibit that displays diagrams of the city in 1896, 2015 and 2050, where a majority of the city has inevitably sunk below sea level due to climate change. While we’ve read about this over the past few years, visually seeing parts of the city, especially your own home, under water makes you pause and think. “Byelaws operate keeping in mind land as you see it today, not what will happen to Mumbai in 2050 because of rising sea levels. With a lot of land submerged, where will the population go? If they have to move, where’s the space to house them? How will that development take place? The byelaws have to consider not just the way the city is today, but [take into account] the scenario 30 to 50 years down the line.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!