A London-based musician-researcher’s novel discovery traces the origins of electronic music in India to a studio in Ahmedabad’s National School of Design

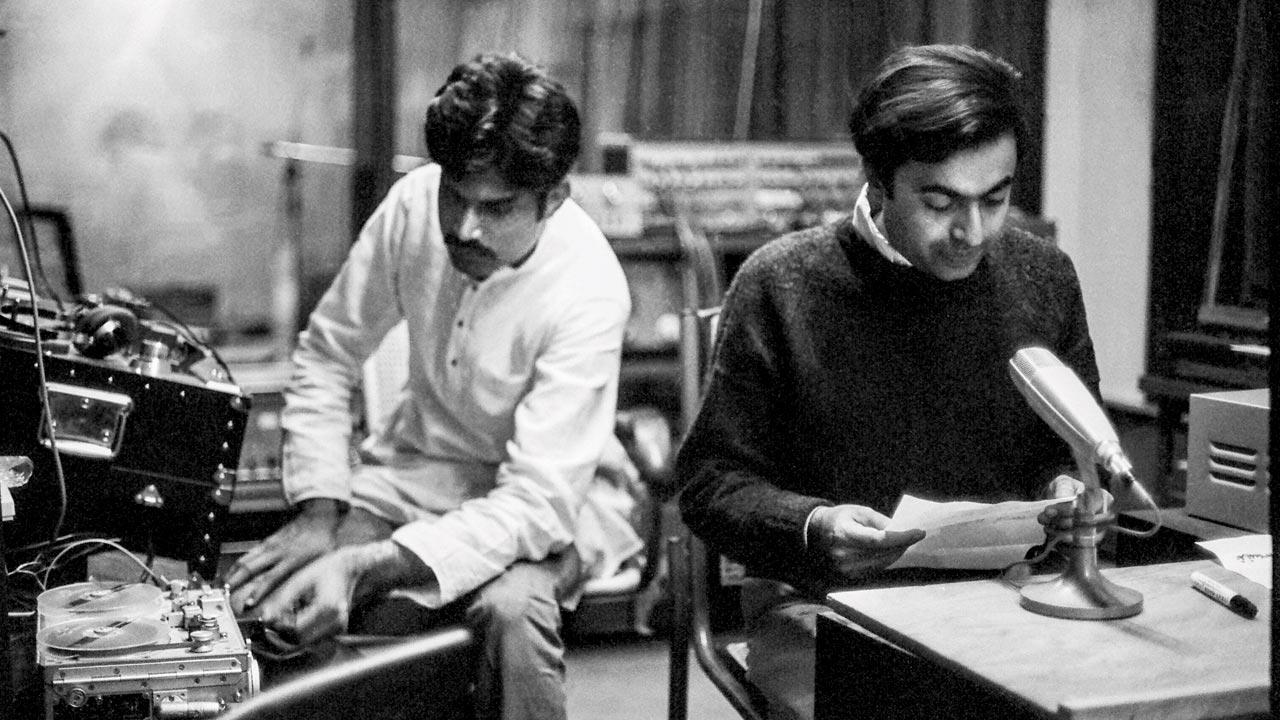

New York-based pianist and experimental music composer, David Tudor came to India in the late ’60s with a Moog synthesiser and set up the country’s first electronic music studio at National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad. Pics Courtesy/National Institute of Design-Archive, Ahmedabad

This is All India Radio, Ahmedabad, Baroda. We now present a discussion of electro-acoustic music conducted by Mr Atul Desai, electronic music composer. Participants in the discussion are Mr IS Mathur and Mr Vikas Satwalekar,” went the announcement on the now Akashvani radio station, in the early ’70s. Following this was a snippet on the origins of electronic music in India. The music composition, few seconds long, wasn’t the fusion-electronic beats you hear these days; it was experimental and loud enough to make your toes curl but it piqued our curiosity.

ADVERTISEMENT

Later this year, a collection of tapes recorded at the National Institute of Design (NID) Ahmedabad, between 1969 to 1972, will be released by UK based independent music label Area 51 records. The NID Tapes are a collection of early Indian electronic music, and will be released as a two-LP edition. A single from the same collection, After the War by SC Sharma, was released last month on streaming platforms. This archival collection is the outcome of Paul Purgas, a London-based musician and researcher’s, digging.

The NID Tapes are a collection of archival recordings which musician and researcher, Paul Purgas traces as the origin of electronic music in India

The NID Tapes are a collection of archival recordings which musician and researcher, Paul Purgas traces as the origin of electronic music in India

How did Purgas get his hands on what is considered to be India’s first recordings of electronic music dating back to the late ’60s? And how did he trace electronic music to this decade and not the ’80s, when early Indian electronic music is usually associated with Charanjit Singh’s 1982 acid-house album, Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat?

“The journey,” says Purgas, “started after I read an article in 2016 about David Tudor coming to India in the late ’60s.” Tudor, who passed away in 1996, was a pianist and experimental music composer. He was known for his association with music theorist and composer, John Cage, a pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electro-acoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments. “This got me curious,” continues Purgas, “because it mentioned NID, a design school, its links to New York avant-garde and an early Moog synthesiser.” A year later, Purgas found himself at NID.

Purgas came back to NID in 2018 with better equipment to listen to the tapes. He consulted the British Library on the correct procedure of handling and preserving archival tapes, which included around 30 hours worth of recording

Purgas came back to NID in 2018 with better equipment to listen to the tapes. He consulted the British Library on the correct procedure of handling and preserving archival tapes, which included around 30 hours worth of recording

The collections include chronicles of electronic music by commercially lesser known composers such as Gita Sarabhai, IS Mathur, Atul Desai, SC Shama and Jinraj Joshipura. They recorded this at the nation’s first electronic music studio founded at the NID by Tudor, who also personally set up a Moog modular system (also known as a Moog synthesiser) and tape machine in 1969. It is a modular synthesiser developed by the American engineer Robert Moog in 1964, and was the first commercial synthesizer. It is credited with creating today’s analog synthesiser.

Purgas’ first trip to NID in September 2017 led to the discovery of the tapes at the Knowledge Management Centre (KMC) in NID. “They were in the archives of the library and it appears that some of the tapes were last heard in the early ’90s, as per the log,” says Purgas. “So people were aware of their presence but I don’t think anyone had an idea of how culturally important they were. They symbolise India’s first major journey into electronic music.” He believes that, “as technology moved from analog to digital, people’s ability and inclination to access these became less and less.”

There is also a curious gap between these recordings, the influence of disco and synth-driven Bollywood film music and Singh’s Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat in the 1980s. “It is about embracing and creating awareness around electronic music in India,” he says. “I don’t believe that the gap was a complete desert. Bollywood was working with Moog in the early ’70s and there were other experiments of bringing in electronic sounds to tracks, but shedding light on NID ‘s role can mobilise some kind of thorough research to fill these gaps,” he says over a video interview.

His research also uncovered the role of the Sarabhai family in Tudor setting up the studio at the institute they founded. “In order to make the space cutting edge for education and innovation, NID had modern equipment, whether it was film and video or the electronic studio,” explains Purgas. “The Sarabhais—Gita and Gautam—were interested in bringing this modern equipment to NID and David was in touch with them. John Cage also visited Ahmedabad in the early ’60s and there were lots of connections between Ahmedabad and the New York artiste community.” What is interesting about the studio, believes Purgas, “is the desire to shape its own identity in the face of social, political and economic conditions of recovering from the British imperial rule and trying to find the resources to build this experimental and forward thinking art and design culture.”

Talking about the music, Purgas says that it was very different from Bollywood. “It was unique with a lot of experimental thinking around design, arts and crafts. It was inspired by modernism, avant garde ideas, a free thinking approach to creativity that went with the radical thinking of the Sarabhai family.”

Purgas was not able to see the original Moog, because it was last known to be in possession of a former NID student, who passed away. Its whereabouts are now unknown. He also didn’t get a chance to see the original studio either.

His process of recovering the tapes started in 2018, when he came back to the institute with his own equipment. He shares that even though NID had a reel-to-reel (an audio tape recording), he chose to not play anything and instead went back to England and contacted the British Library for their guidelines on how to correctly handle and preserve old reel analog tapes and the equipment required while working with them.

“I brought a reel-to-reel recorder from the UK and a small food dehydrator because I was advised that some old tapes start to degrade and need to be baked in an oven to reset the chemicals to be played again. I had to bake three tapes,” he recalls. All in all, he managed to salvage 30 hours of audio. “I didn’t know what I was going to discover on the tapes, but it was experimental music in its purest form and I had never heard anything like that so early in that time coming out of India. I was both surprised and amazed at the recordings I heard.”

The records will also be accompanied by a book, titled Subcontentinental Synthesis: Electronic Music at the National Institute of Design, India 1969–1972 (Strange Attractor Press and MIT Press) which is edited by Purgas. The book will be a collection of critical essays that will reflect on the larger cultural and political dialogues surrounding the studio as well as written contributions by Geeta Dayal, You Nakai, Rahila Haque and Jinraj Joshipura, the last surviving composer from the NID.

Interacting with Joshipura was an extraordinary experience, Purgas recalls. “Even after 50 years, he is still passionate about electronic music.” Purgas tells us that Joshipura was just 19 years old when he heard about Tudor hosting electronic classes, and managed to get into the programme. “He told me about David challenging him to make his first composition, and how he was inspired by Stanley Kubrik’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and decided to make his own version of a sonic journey which turned out to be Space Linear 2001. To hear this and the imagination of a 19-year-old electronic composer from India in that moment was really magical,” shares Purgas.

He believes that it would be amazing to have someone read about the NID Tapes and trigger a thought or memory in them or some other activity that might have happened at the same time. “I hope this work can help set in motion some other research on this subject,” he concludes.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!