Thane trekkers, whose association with residents of the Raigad village destroyed in the landslide began with the death of their fellow climber, speak of the pain of watching what they built crumble

Members of Janiv NGO from Thane convinced the Irsalwadi villagers and its gram panchayat to let them help build this school, the only standing structure post the July 21 landslide. Pic Courtesy/Janiv

Lalita Umtambra, fresh from having acquired a degree in nursing, was ready to start her first job at a Neral clinic on July 19. Heavy rains back home in her village of Irsalwadi saw her wait it out a few days. The landslide that buried the Raigad taluka village under 30-feet of debris on July 21, took Lalita’s life.

ADVERTISEMENT

The young woman, like most other children of the village, began her education at a primary school set up by a group of trekking enthusiasts from Thane. Over the years, the school became as much a part of the villager’s lives as of the Thanekars who helped build it brick by brick.

A resident of Irsalwadi, Khalapur, whose family was wiped out in the July 21 landslide. The death toll officially stands at 57; 83 persons are still unaccounted for. Pic/Getty Images

A resident of Irsalwadi, Khalapur, whose family was wiped out in the July 21 landslide. The death toll officially stands at 57; 83 persons are still unaccounted for. Pic/Getty Images

On January 23, 1972, the group had set off to scale the craggy, weather-beaten peak of Irsalgad, at whose base sat the village. They were halfway up there when tragedy struck and the leader of the group, Prakash Durve, slipped off the edge.

“The residents rushed to help; we searched together for hours till we found his body. They also helped us carry it down the treacherous terrain to the Chowk village. They were selfless in the way they rallied around us. It was the beginning of a lifelong relationship that’s not unlike family,” Satish Waivude tells mid-day.

Janiv members convinced the villagers to trust them to help build a well. Until then, the residents would collect around this pit to draw filthy water and bathe. Deveshu Thanekar, the son of the one of the core group members, recalls visiting the village every Independence and Republic day to hoist the flag in the school compound. Pics Courtesy/Janiv

Janiv members convinced the villagers to trust them to help build a well. Until then, the residents would collect around this pit to draw filthy water and bathe. Deveshu Thanekar, the son of the one of the core group members, recalls visiting the village every Independence and Republic day to hoist the flag in the school compound. Pics Courtesy/Janiv

Waivude and friends Sharad Ovalekar, Shrikrishna Gokhale, Ravi Dongaonkar and Manvendra Thanekar, made regular trips to Irsalwadi in the months to come, and realised that even for the 1970s, the tribal settlement was living in the dark ages. There was no organised sanitation; water was drawn from a large pit which animals also bathed in; and education facilities didn’t exist. They decided to form a non-profit that they named Janiv under Ovalekar’s leadership. In 1976, Janiv held its first camp in Irsalwadi to educate the villagers about the importance of sanitation and hygiene. The same year, work began on the construction of a well. Unfortunately, the task wasn’t minus hurdles.

“A city dweller was a suspicious person to them. They had never been exposed to outside interaction and insisted that their water pit was sufficient,” Dongaonkar recalls.

During this time, Janiv members noticed that the nearest school for Irsalwadi’s children was in Chowk village, a one-hour trek each way down a single, narrow path through the mountain. It was why the kids there didn’t go to school. Their parents earned their livelihood by selling wood foraged from the forest, working as daily wage labourers and farming rice a few months of the year.

It was slow work but Janiv managed to convince the Irsalwadi gram panchayat to sanction a school in the village in 1993. This was 20 years since their first interaction with the locals. The struggle, however, had just begun.

(From left) Shrikrishna Gokhale, Satish Waivude, Deveshu Thanekar and Ravi Dongaonkar, members of Thane-based NGO Janiv, flip through an album that holds memories of their work in ill-fated Irsalwadi, which they helped build from a tribal settlement to a bustling village. Pic/Satej Shinde

(From left) Shrikrishna Gokhale, Satish Waivude, Deveshu Thanekar and Ravi Dongaonkar, members of Thane-based NGO Janiv, flip through an album that holds memories of their work in ill-fated Irsalwadi, which they helped build from a tribal settlement to a bustling village. Pic/Satej Shinde

“Because of the hard and long route up to the village, no contractor was willing to take up the work. Labourers, too, refused to ferry the heavy construction material. For the first four years, the proposal stayed on paper. Finally, we convinced the villagers to help carry the material up to the village, in exchange for a daily wage remuneration,” Gokhale tells us. “While we were struggling to find contractors and labourers, we were also trying to convince the villagers why they needed a school in the first place. It would be years before they finally agreed, and only then did we start construction together in 1997. We had around R1 lakh in funding from the panchayat, to which we added R35,000 from our own pockets so that the villagers could be compensated for labour,” he says.

In 2003, Kashinath Pardhi, who completed his primary education at the school, became the first Irsalwadi resident to appear successfully for the SSC exam and went on to earn an HSC degree in 2005. “Pardhi was in charge of the donation box at the school, where visitors could contribute what they wished to towards the development of the village, till he, unfortunately, passed away in this month’s landslide,” says Waivude. “He’s missing!” Manvendra’s son Deveshu quickly interrupts. The older men share a look; sometimes it’s best to leave things unsaid.

Shrikrishna Gokhale

Shrikrishna Gokhale

The death toll from the July 21 landslide officially stands at 57; 83 persons are still unaccounted for. The National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) called off its operation earlier this week due to incessant rains and suspected rotting of bodies under the debris.

For Deveshu, the blow is as hard as it is for Gokhale, Waivude and Dongaonkar. His father, who was at the forefront of the efforts to build the school, passed away last year. “Three brothers from the village studied at the school and went on to become Home Guards,” he tells us proudly, like a doting elder brother would.

A video that Deveshu shared on YouTube recently, documenting Janiv’s association with the village, was shot in 2012 for a travel channel. “We have held countless medical camps there. Every year, we would go there on Republic Day and Independence Day to hoist the national flag in the school’s compound, and come back with a list of supplies that the villagers needed,” he says.

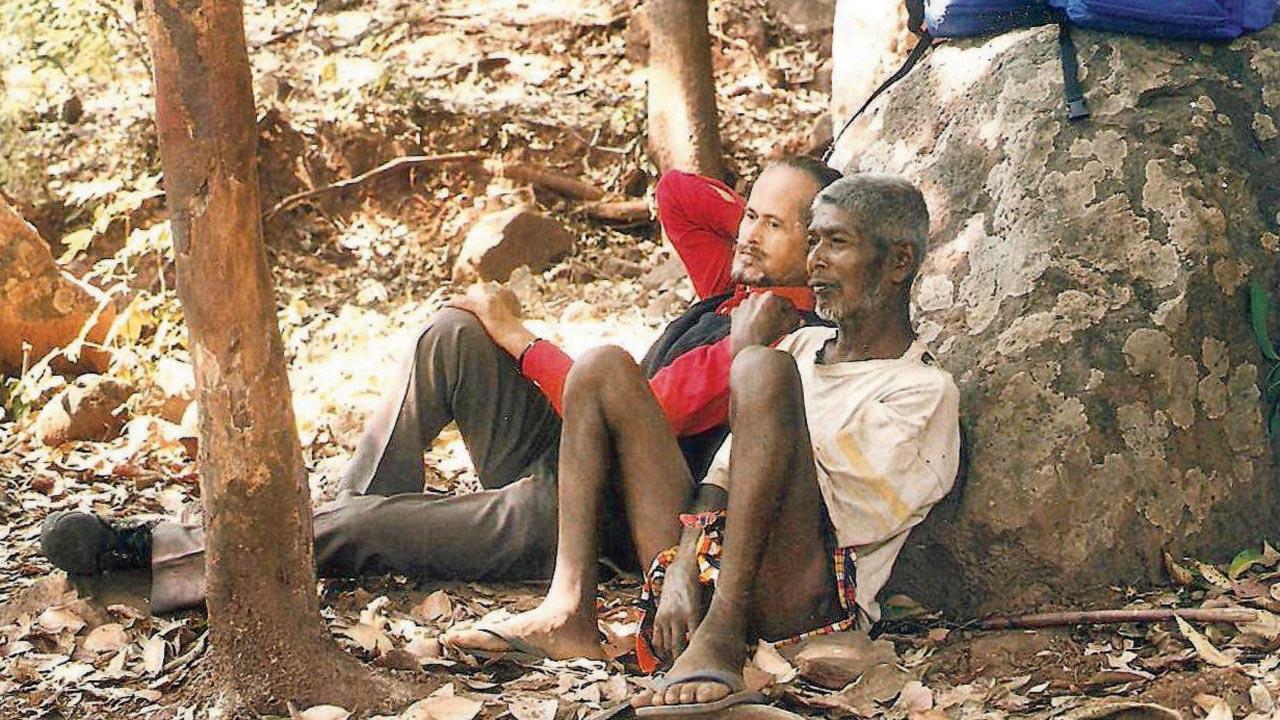

Janiv founder Sharad Ovalekar relaxes with a villager during one of their many visits

Janiv founder Sharad Ovalekar relaxes with a villager during one of their many visits

The school, which was operational till 2018, was currently shut because there were no children in the age group of Class I to IV to study there. The Zilla Parishad rules dictate that there should be a minimum enrolment of 21 students for a government-aided school to stay operational.

Fatefully, the school is also the only structure still standing after the landslide, and was used by the NDRF to set up camp.

“A group of 10 to 12 young boys had gone to the school the night before the landslide, to watch movies on their phones; the school is the only spot where you get decent mobile network. They escaped death and were also the first to raise an alarm when they heard the rocks come crashing. They ran all the way down to Chowk and alerted the authorities to begin rescue efforts,” says Gokhale.

Janiv continues to closely monitor the ongoings. “We visited the spot and saw that the village is currently inundated with supplies that have come in from good Samaritans and government agencies. We will continue to track if all the promised aid reaches them. We are also trying to identify orphans, single women or anyone else who has been been left without family, and plan to support them in any way possible for the next four to five years,” Gokhale says.

With inputs from Shirish Vaktania

Rs 1 lakh

The funding that Janiv received from the Irsalwadi gram panchayat for the school

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!