An urban designer collaborating with the Pune municipality for a one-of-a-kind project to make school zones safer, says cities have a chance to get children on the roads

A 3D visual of the plan Kharadi South Main Road in Pune, which has nine schools on the stretch, shows segregated cycle tracks and walkways, play areas along multi-utility zones, painted junctions designed for safe crossing of school children, pedestrian signals, traffic calming measures, and signage. Courtesy/Abhijit Kondhalkar

Pune-based urban designer Abhijit Kondhalkar’s obsession with a safe school travel plan began when he first read a quote by Enrique Peñalosa, mayor of the Colombian capital Bogotá. “Children are a kind of indicator species,” Peñalosa had stated, “If we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for all people.” “That quote stayed with me,” Kondhalkar tells us over a phone call. “I kept thinking what I could give my kids as an architect and urban designer. I was looking to demonstrate the ideas that I had in mind to create a clean, safe and resilient city for children.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The opportunity came in June last year, when the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) organised an urban design competition for its proposed School Travel Improvement Plan. “As part of the competition, the PMC had identified school zones, each with around 10 schools. Participants had to select one zone, study it, understand how people and children move within it, and demonstrate an idea to improve it.” Kondhalkar, who is co-founder and principal architect of ARKMIRA Architects and Planners, says their idea was declared the winner. This set the ball rolling for a unique project that is being spearheaded by the Pune municipal body.

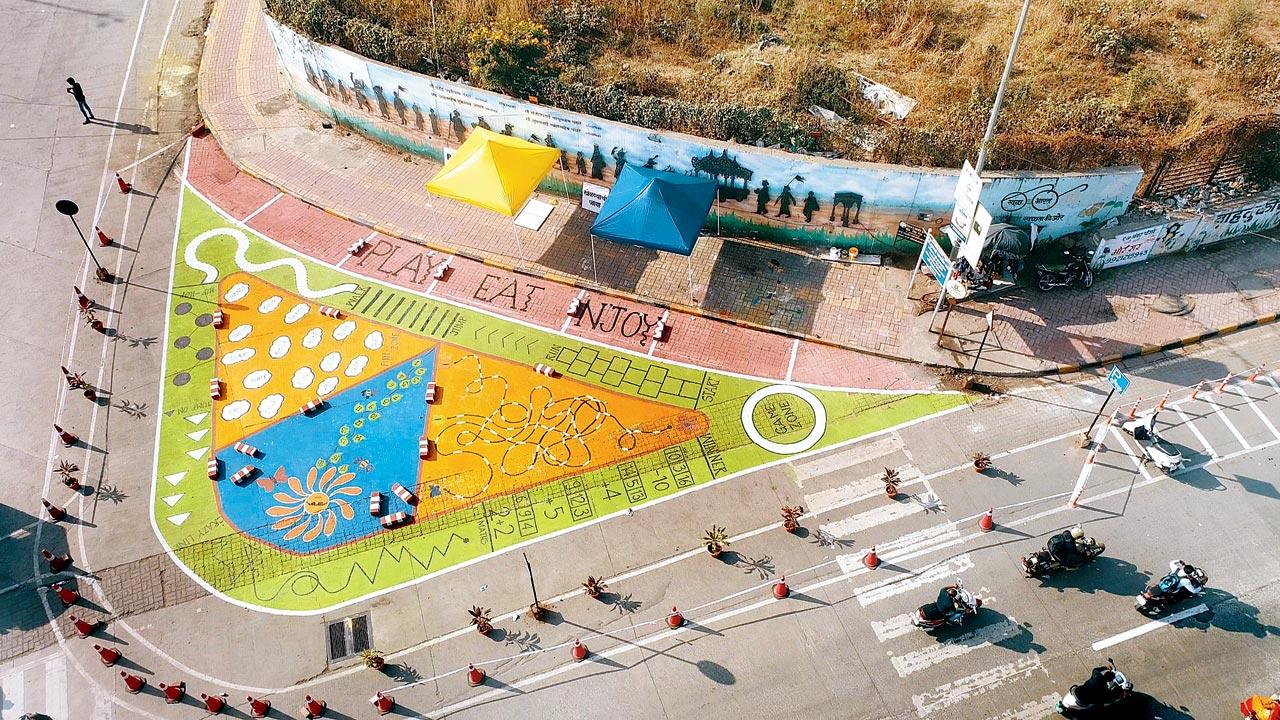

A pilot project by Abhijit Kondhalkar and team on the Kharadi stretch showed how a motorised stretch near a school could be made safe for children. The interventions included carving out play streets and sit-out spots in areas that were earlier utilised for parking or hijacked by street vendors; these stretches have been colourfully painted. Cycle tracks were created by placing bollards

A pilot project by Abhijit Kondhalkar and team on the Kharadi stretch showed how a motorised stretch near a school could be made safe for children. The interventions included carving out play streets and sit-out spots in areas that were earlier utilised for parking or hijacked by street vendors; these stretches have been colourfully painted. Cycle tracks were created by placing bollards

Last December, Kondhalkar and team, which had presented an area-level plan for Kharadi South Main Road, home to nine schools, carried out a pilot on the stretch, to showcase how their award-winning interventions could be implemented on ground. The ideas included carving out a cycle track by placing bollards, colouring the street, and redesigning the junction. These interventions and more, will soon find a permanent place.

Over a month ago, the PMC introduced a rigorous set of guidelines for the 19 zones identified under the School Travel Improvement Plan. These define “suitable infrastructure and measures for children to travel safely and independently to and from school”. Kondhalkar’s team is collaborating with transportation planner Nikhil Mijar with the PMC, traffic department, and the WRI India, Parisar and the Safe Kids Foundation, to revitalise the Kharadi school zone.

Kondhalkar explains what made the zone unsafe for children. “The street [we were working on] has six lanes. When school resumes for the day, there’s extreme chaos at the gate, with kids spilling onto the street, causing accidents. Every year, there are at least four to five accidents reported due to this,” says, adding, “Children also face a lot of difficulties crossing the junction. Around the zone, there are illegal parking spots occupied by private caps and wine shops, which make young school-goers vulnerable to eve teasing when walking on the footpaths.” In general, he feels that the way Indian cities are built, makes parents feel less confident about sending their children to school independently. “We don’t have continuous cycle tracks and footpaths and safe crossings that children can use. Parents fear motorised traffic and hence, discourage kids from walking.”

In 2020, the Road Transport and Highways had released a report, which stated that 31 children die in road crashes every day on the streets of India.

This, he says, prevents children’s interaction with the natural and built environment around them, and the social bonding and friendship they could have had with fellow students, while walking or cycling to school.

Abhijit Kondhalkar

Abhijit Kondhalkar

“For the Kharadi zone,” says Kondhalkar, “the idea is to create a safe, accessible, inclusive, playful, and green space.” As part of the plan, they’ve proposed a 5 km-loop of pedestrian and cycle network, connecting Kharadi South Main Road, Magarpatta Road, Nagar Road, and Fountain Road. The loop has been named The Green Ribbon. It will have segregated cycle tracks and walkways, play areas along multi-utility zones, junctions designed for safe crossing of school children, pedestrian signals, traffic calming measures, and signage.

This will provide safe access to 14 schools. “Almost 7,000 schoolchildren will enjoy a pleasant walking and cycling experience along The Green Ribbon.” Additionally, all streets falling along the green ribbon will be declared as school priority streets and will observe a speed limit of 25km/hour, strict implementation of parking policy, dedicated hawker zones, and an ample amount of space for cycle parking. “The neighbourhood level streets will have a ban on heavy vehicle movement during school hours.” Kondhalkar says they’ve also incorporated rumble strips—sleeper lines or alert strips to alert inattentive drivers of potential danger—which are usually found on the highways. “It’s time that we incorporate them within the city,” he feels. The other plan is to paint the roads next to the school, to indicate drivers to reduce their speed.

The project is in the final stages of implementation, and Kondhalkar says he is “filled with optimism” about the future of India’s cities.

According to him, a project of this nature, with the interventions they’ve suggested, would cost around R1.5 crore per 1 km street. “Some of our cities have annual budgets that runs into thousands of crores, so this should not pinch their pockets.” He says cities like Mumbai, where space seems to be in wanting, should take a leaf out of Tokyo, instead of the highly motorised Western cities. “Tokyo has a population of 40 million, while Mumbai has an estimated population of 12.5 million. If Tokyo can implement projects that focus on non-motorised traffic, Mumbai can too,” he says, “What is currently lacking is focus and intent on infra for pedestrians. This infrastructure will determine the health of a city.”

31

No. of children who die in road crashes every day on the streets of India, according to a 2020 Road Transport and Highways report

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!