Home / Sunday-mid-day / / Article /

Whose suit is it anyway?

Updated On: 20 February, 2022 07:41 AM IST | Mumbai | Heena Khandelwal

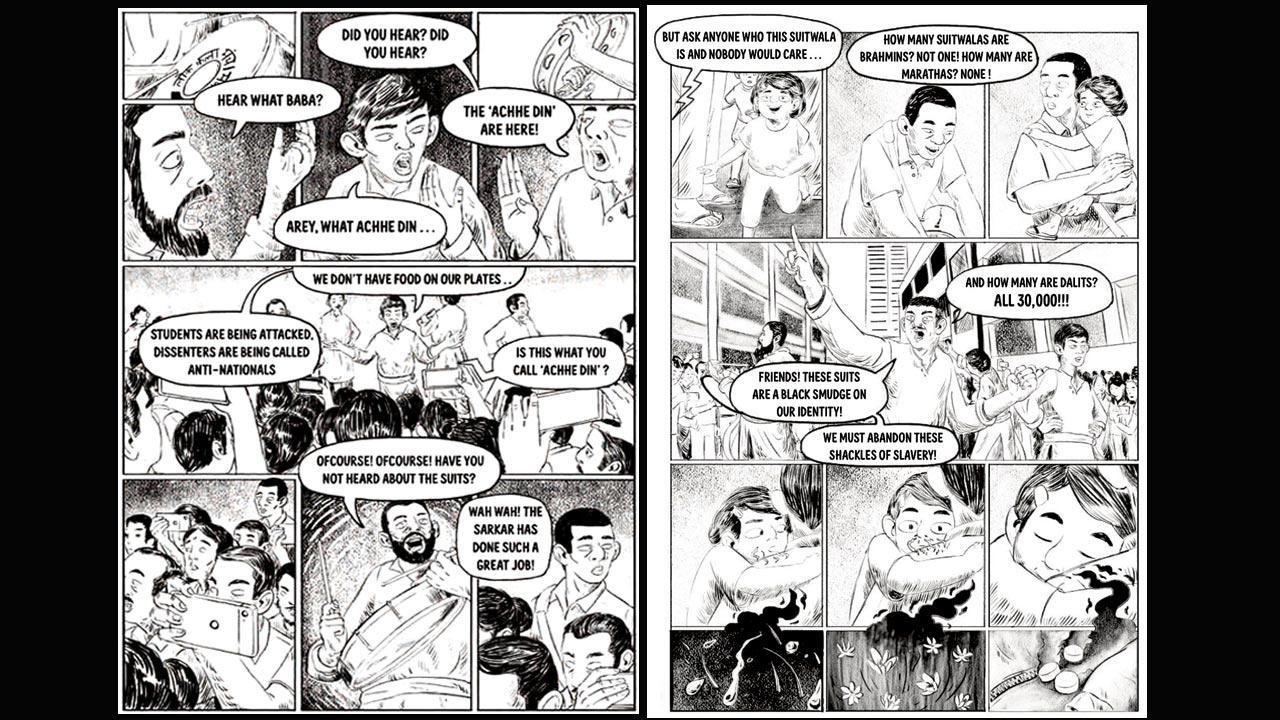

A graphic novel takes us into Mumbai of the near future, where safai karamcharis have topnotch safety equipment and equal rights, but still fail to live a life of dignity

The book revolves around Vikas, a conservancy worker from Mumbai of the future, who finds himself stuck in the vicious circle of casteism despite having a secured government job and safety equipment, including a full-body suit

Does anyone know how people die in sewers? That’s the question author-illustrator Samarth poses to his readers, right at the beginning of his just-released debut graphic novel, Suit (Yoda Press, Rs 295). The answer comes to the reader immediately in a distressing graphic of a mouse reacting to Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) gas—typically formed in wastewater collection systems—as it slowly enters the rodent’s body. The human body responds in a similar manner, slowly slipping into a coma. The book then takes readers into the city of Mumbai of the future, where manual scavenging has been eliminated and conservancy workers are relatively more secure with safety equipment, including a full-body suit, leading to them being called “suitwalas”. They also have government jobs, consistent salary, and ID cards—all assuring a hope of a better future. Despite this, Vikas, a safai karamchari, and the protagonist of the novel, finds himself stuck in the vicious circle of casteism. “I think it was very important for me to delve into the humane side of my protagonist. He has seen his father, also a manual scavenger, dying in a sewer. He has also seen work conditions of his community improve for the better. He shares a relationship with his daughter that is very different from the one he shared with his father, has access to opportunities and yet nothing is perfect. This transition was something very central to the story,” says Samarth, 25, an alumnus of IDC School of Design, over a telephonic interview.

The idea for the book, that’s available in bookstores, came to Samarth, who prefers to be identified by his first name, in 2017, when he went to Israel for an exchange programme and volunteered to teach filmmaking in collaboration with an NGO in Palestine for a month. “It was a system of violence, oppression and cruelty, institutionalised by the Israeli government towards the people of Palestine. After I returned to India, I realised I was getting more affected by injustice around me. Not that I wasn’t aware of the violence and injustice earlier, but it had started bothering me more,” says Samarth, who grew up in Mumbai.