Reports of avenging monkeys in Beed killing pups over two months has left primatologists puzzled. They discuss why this behaviour can be expected of humans and chimps but not langurs

A group of langurs in Pushkar, Rajasthan, photographed while fighting for food. Experts say that while animals do compete for resources such as food and space, they don’t go to “war”. Pic/Getty Images

Last week, Beed district in central Maharashtra grabbed the headlines for a rather bizarre incident. According to local news reports, a clan of monkeys killed 250 dogs over a month or so by dropping them down from buildings and treetops. What’s being seen as “revenge” allegedly had its roots in an incident where a pack of dogs mauled a baby monkey to death. In a subsequent interview with the Wire, Sachin Kand, the divisional forest officer of Beed clarified that while the Hanuman langurs did snatch up puppies in Majalgaon, they ‘lifted’ only three, and not 250 as some news reports claimed. Two monkeys that were allegedly involved in the killing have been captured by the Nagpur Forest Department and will be released in a nearby forest, Kand said in a statement.

ADVERTISEMENT

Over the years, researchers have been sussing out various aspects of primate behaviour and psychology, but the idea of simians seeking revenge has been a tough one to crack. “You need a highly evolved brain for that. We see it [tendency to avenge] in humans, and to an extent even in chimpanzees, who come closest to humans, but not in langurs. In fact, I have witnessed a number of instances where they [langurs] are riding piggyback on dogs, and even cuddling them,” says primatologist Rishi Kumar, who researched the sand-coloured Rhesus macaque, and Bonnet macaque, commonly found at temples in South India, for his PhD. The Hanuman langurs (Semnopithecus entellus) in question are found in a range of habitats from tropical rainforests in the Western Ghats to over 3,000 metres in the Himalayas. This species is predominantly leaf-eating and arboreal. According to Kumar, what typically happens when a female monkey loses an infant, is that she takes away the infant of another female and carries it for some time. “In Hanuman langurs of Maharashtra, it’s usually a multi-female group, where there’s one male and several females. There’s a pecking order in both [multi-female and multi-male groups]. We also see proactive alloparenting among them, wherein monkeys other than the mother assist with infant care. In the Beed incident, there’s footage of the monkey carrying the pups. I believe there’s a good chance that she might have taken the pup not with the intention of killing it, but fostering it for a while. The pups may have died while she was climbing the tree, or from starvation.” Revenge is highly unlikely, thinks Kumar.

A Himalayan langur with an infant. Foster parenting is common among monkeys. When a female monkey loses an infant, she takes away the infant of another female and carries it for some time

A Himalayan langur with an infant. Foster parenting is common among monkeys. When a female monkey loses an infant, she takes away the infant of another female and carries it for some time

Researchers observe that the females will fight fiercely to thwart the advances of infant-snatching males. Why they are so loyal to their fellow troop mates is yet to be ascertained.

Most langurs are greyish, brownish or blackish, with paler underparts, and communicate using a wide variety of sounds, including harsh barks, rumble grunts, honks, rumbles and hiccups.

A dog waits for a monkey to descend from the tree in Mandal Valley, Uttarakhand

A dog waits for a monkey to descend from the tree in Mandal Valley, Uttarakhand

Kunal Arekar is an evolutionary biologist studying systematics and evolutionary origins of various primate species in the Indian subcontinent using molecular phylogenetics as a tool. As the co-founder of the Association of Indian Primatologists (AIP), Arekar has been investigating the Beed incident. He says while animals do compete for resources such as food and space, they don’t go to “war”. It’s competition. The incident in Beed might be unusual, but not baffling, he thinks. “Animals don’t have the concept of revenge and certainly not so deliberate where they are plotting murders over two months. For the most part, these acts of ‘revenge’ take place shortly after the attack. Although it’s impossible to know what exactly happened in Beed, one of the many possibilities is that both the dogs/puppies and langurs might be competing for the same food resources, which might have led to this interaction,” explains Arekar. Langurs are known to be extremely shy. “Unless they are habituated to being around humans, they won’t come anywhere close to settlements. They mostly forage on the outskirts because they are dependent on forests,” shares Arekar.

Hanuman langurs are known to be peace-loving creatures. Aggression and dominance is seen only when it comes to food and mating. “The dominant males will fiercely defend his females. So if a new male takes over a troop, he will usually commit infanticide, killing all the previous males’ offspring, so that he may create his own faster. It’s a reproductive strategy. As males lose their prime youth, they go down the hierarchy,” observes Kumar.

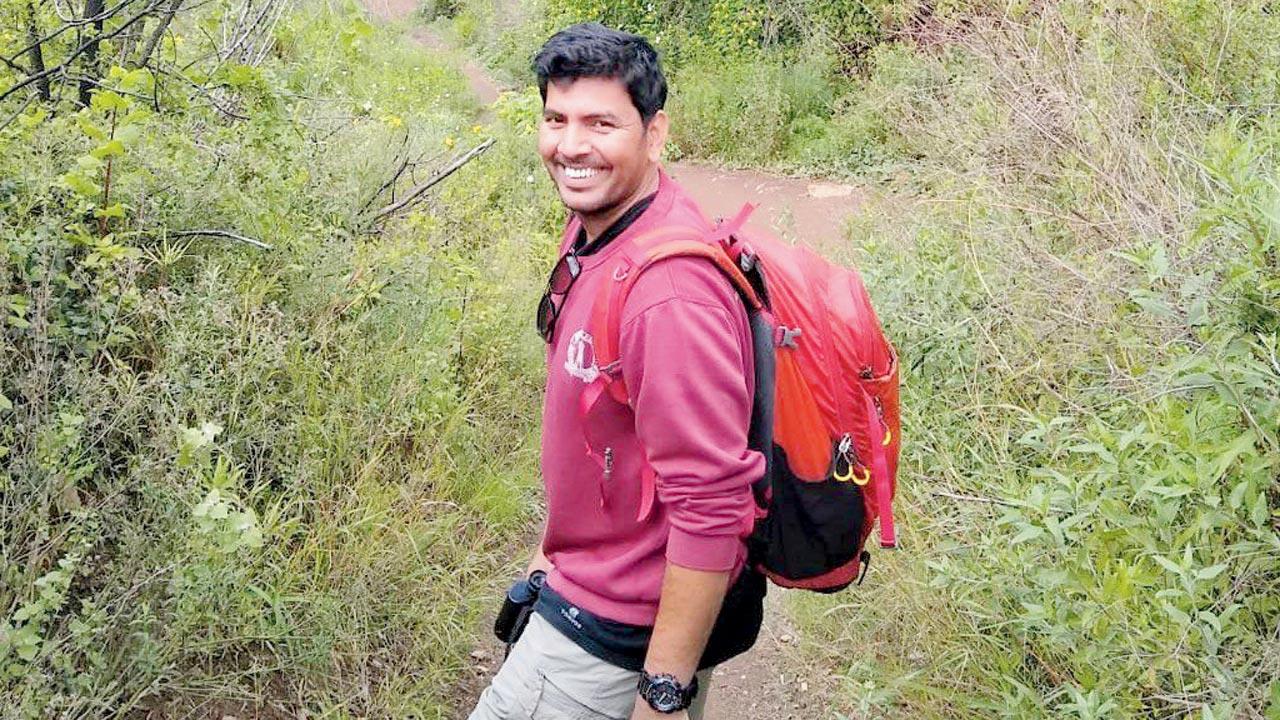

Kunal Arekar

Kunal Arekar

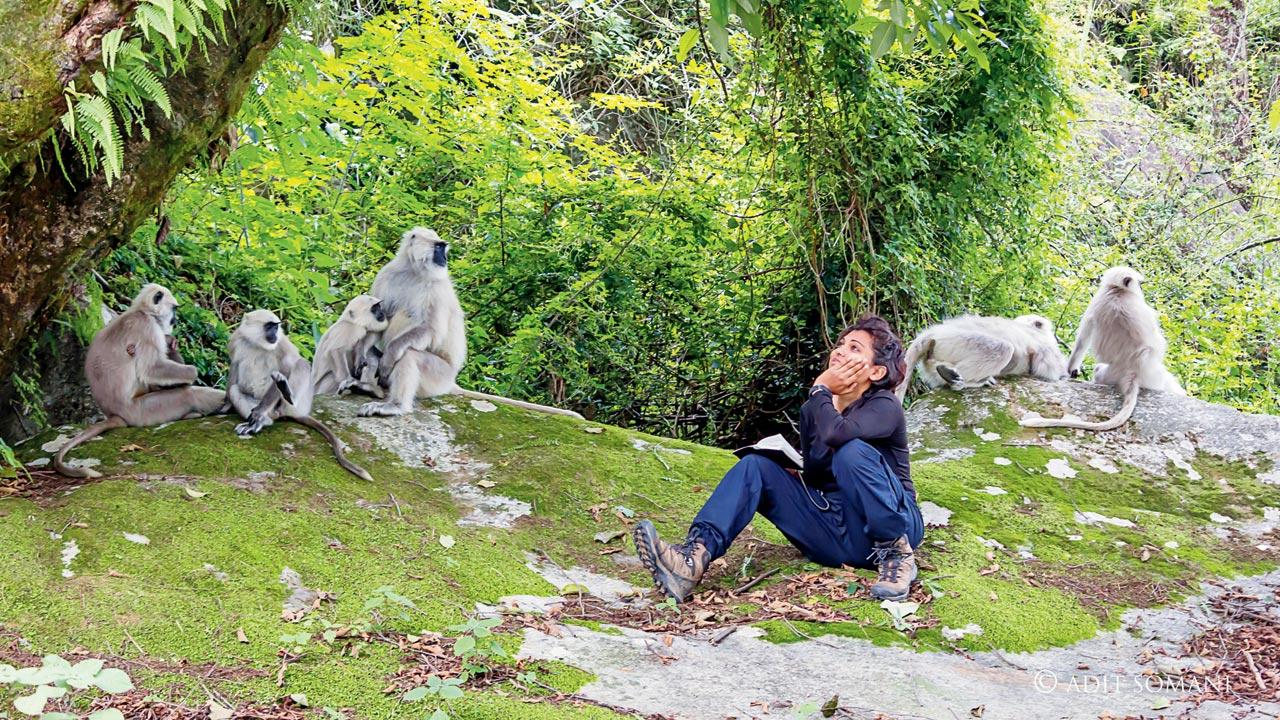

Himani Nautiyal, a biological anthropologist with a PhD from Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University Japan, has been extensively studied the Himalayan Langur (Semnopithecus schistaceus), one of the least-studied species of langur, in the western Himalayas for seven years. According to research, the Himalayan population of Hanuman langurs have now been classified as a distinct species with multiple subspecies. “From what I’ve studied in regions of Uttarakhand, dogs are predators for langurs. In retaliation, the monkeys may not kill the dogs, but may chase them away and that’s something I’ve seen first hand. They do this by ganging up.” While conducting her research in a forest, Nautiyal recalls an incident where an infant monkey accidentally fell off the tree. “There were a few dogs around who grabbed the infant, but the monkeys managed to yank the baby back from the dogs and even chased them away. Then there are also highly aggressive dogs who have been trained to drive away monkeys; this happens on farmlands when villagers make pacts to get rid of crop-raiding monkeys.”

Nautiyal says the study of primates in India is still at a nascent stage. In a paper published in Folia Primatologica in 1974, American anthropologist and primatologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy‘s findings on Hanuman langurs in India suggested that infant-killing by male langurs was a reproductive strategy. She also found that fertility was a decider in hierarchy. Nautiya’s research, however, has shown otherwise. “In the group that I was observing and studying, the alpha females are old and not fertile anymore. They cannot mate anymore. So it’s an evolving field of study.” In an interview with a scientific website, Hrdy admitted that those were early days in primatology. “I doubt that my casual observational methods would be acceptable today,” she said. Kumar agrees. It’s only in the last 50 years that has there has been an earnest scientific attempt to understand primates. “Before that they were notes about behaviour, but it wasn’t systematic. Which is why it’s difficult to expand on their evolution,” he shares.

Himani Nautiyal, biological anthropologist

Himani Nautiyal, biological anthropologist

What’s common to langurs both in the plains and the mountains, feels Nautiyal, is their shyness. But when it comes to adaptability, the sky’s the limit. “When they are in the forest, they are extremely elusive. I had a tough time tracking them. But, the ones living in the town are smart and humble too. If the humans don’t mess with them, they will never be a bother.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!