This evening, watch a documentary that captures a Mumbai nonagenarian's undying love for Western Classical music

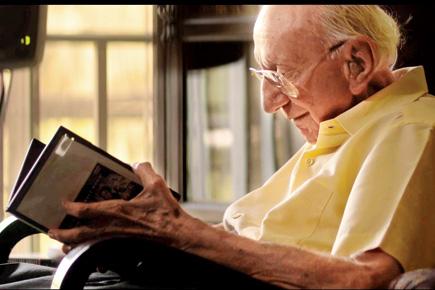

Homi Dastoor with a DVD of a Beethoven symphony orchestra in a still from The Ninety First Symphony u00c3u00a2u00c2u0080u00c2u0094 The Musical Journey of Homi Dastoor

![]() Sitting in his Bandra home, 91-year-old Homi Dastoor recounts a childhood memory, as the camera zooms in on his radiant smile and glinting eyes. When he was eight, Dastoor's mother got a tailor to stitch six pairs of shorts that fell two inches below his knees. Embarrassed to go out and play in them, Dastoor began reading every single book on Western Classical music that he could lay his hands on. “That's how it started,” smiles Dastoor, who spent hours in libraries, attended every live concert Mumbai would host and penned meticulous notes on maestros, which finally became the manuscript for his first book, Musical Journeys: A Personal Introduction To Western Classical Composers. This, he published at the age of 89.

Sitting in his Bandra home, 91-year-old Homi Dastoor recounts a childhood memory, as the camera zooms in on his radiant smile and glinting eyes. When he was eight, Dastoor's mother got a tailor to stitch six pairs of shorts that fell two inches below his knees. Embarrassed to go out and play in them, Dastoor began reading every single book on Western Classical music that he could lay his hands on. “That's how it started,” smiles Dastoor, who spent hours in libraries, attended every live concert Mumbai would host and penned meticulous notes on maestros, which finally became the manuscript for his first book, Musical Journeys: A Personal Introduction To Western Classical Composers. This, he published at the age of 89.

ADVERTISEMENT

Homi Dastoor with a DVD of a Beethoven symphony orchestra in a still from The Ninety First Symphony — The Musical Journey of Homi Dastoor

Currently working on a book on music for kids, he is also the subject of The Ninety First Symphony — The Musical Journey of Homi Dastoor, a 20-minute documentary helmed by Rafeeq Ellias. Produced under the banner, Fat Mama Films, the documentary will be screened this evening as part of NCPA Reality Check, in collaboration with Indian Documentary Producer's Association.

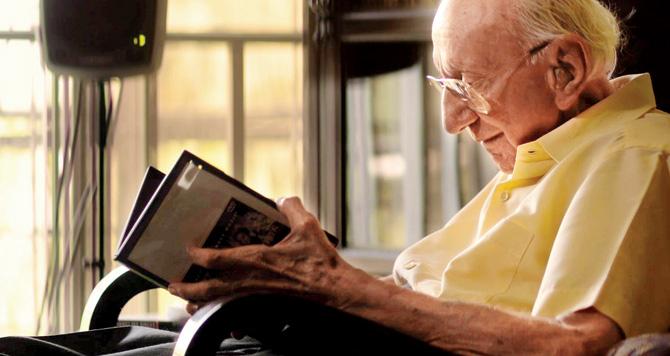

Dastoor in a still from the docu

“Two years ago, a young American student was interning with me. He showed me an article about Mr Dastoor, and his book. We met him together. I was bowled over by his passion and extraordinary lucidity at 90. The film is a portrait of an 'ordinary extraordinary' man, presented as a tribute to him around the time of his 91st birthday last year, hence the title,” says the award-winning filmmaker, acclaimed for the landmark film, The Legend of Fat Mama (2003), on the Chinese community in Kolkata.

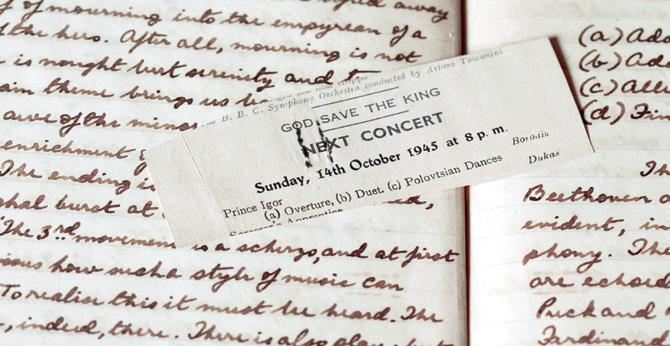

A page from Dastoor's handwritten notes, dating back to 40s and 50s, which include a glossary of Western Classical music composers and their works, along with a ticket for an orchestra concert in 1945

Dastoor, once an executive in the sales department of Tata, is seen in the film, wearing a hearing aid, enraptured by a symphony orchestra playing on television, as his fingers unconsciously conduct the tunes. “I watched him entranced by the music of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Herbert Von Karajan. His delight in describing the nine symphonies of Beethoven as the spinal column of the Western Classical music repertoire still rings in my ears. There's also an amazing academic side to his passion — his knowledge of the vast discipline of Western Classical music and its grammar that he believes a listener should familiarise himself with,” shares Ellias, who shot for two hours at a time on four to five

occasions, in deference to Dastoor's age. For him though, age is just a number. After all, he decided he'd learn the violin when he retired at 75.

A newspaper clipping from '50s that Dastoor has preserved

The film is also interspersed with nuggets about masters like Chopin and Bach that Dastoor doles out. “He described each composer and their piece of work with such immediacy and wonderment, as if he was there in their presence.

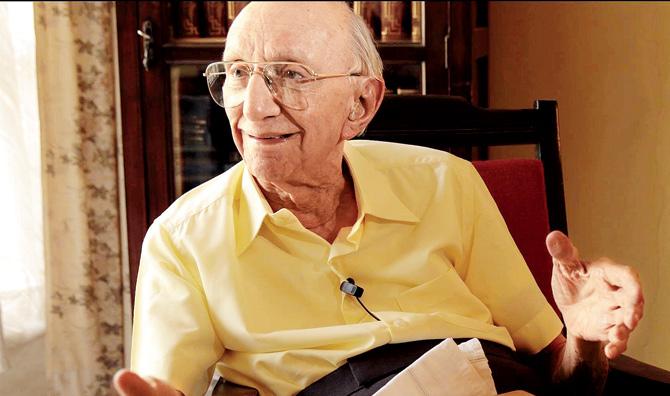

Director Rafeeq Ellias

His descriptions of Beethoven's (who was tragically deaf) first public performance and the standing ovation that he could not hear were mesmerising,” says Ellias, adding that the self-effacing nonagenarian urged the filmmaker to focus on the great composers rather than on him. “That is exactly what makes him special. I kept emphasising that were as interested in him as in Western music.” Perhaps, that's why in his foreword to Dastoor's book, maestro Zubin Mehta writes, 'I salute Homi Dastoor.'

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!