The play, Bombay Jazz takes you back to the swinging city of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, where Hindi film music was largely influenced by Western music

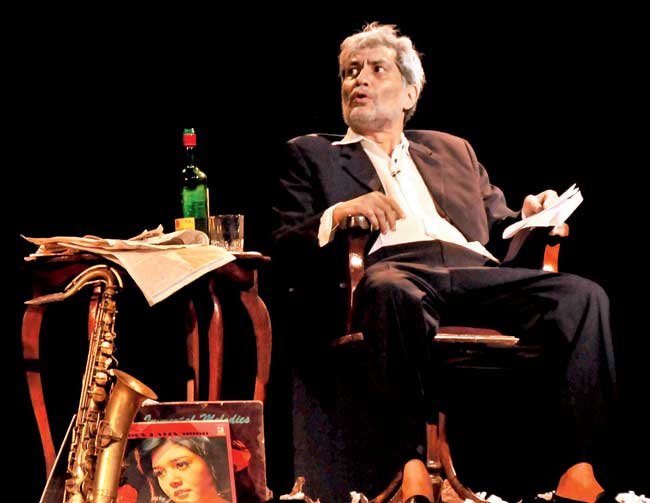

Denzil Smith

In 1935, a violinist from Minnesota named Leon Abbey brought the first African American Jazz band to Bombay, leaving a legacy that would last three decades. In the 1940s, Jazz found its way into popular Hindi film music. Songs like Mera Naam Chin Chin Chu (Howrah Bridge, 1958) became huge hits.

ADVERTISEMENT

Denzil Smith in Stagesmith’s play, Bombay Jazz

In sync

“When I was exposed to Jazz, I realised that, in India, it was being performed at a very advanced and sophisticated level. I wanted to know how it all started. My research showed me that Jazz started in India in the 1920s, which is the same time as when it started in America. We have generations of Jazz musicians in India today,” says journalist and author of Taj Mahal Foxtrot, Naresh Fernandes, whose research forms an integral part of the play. “We found stories of Goan trumpet player Frank Fernand, whose epiphanic encounter with Mahatma Gandhi drove him to try to give Jazz an Indian voice; Chic Chocolate, who was known as the Louis Armstrong of India; Anthony Gonsalves, who lent his name to one of the most popular Hindi film tunes ever,” he recalls.

Chic Chocolate and his band in costumes from the film Albela (1951), after one of the songs, in which the band featured, became a hit

Actor-producer Denzil Smith explains, “Naresh had done some research in 2005. I took that research work and gave it to Ramu (Ramanathan) who started writing the script. We met a few remaining members of the families of these Jazz musicians. During these interviews, they shared photo albums that had some rare photographs. We asked them if they could loan these to us for some time, but they refused as these were heirlooms and they didn’t want to risk losing them. So I learnt my lesson, bought a scanner and when Naresh would meet these people, I would quickly scan a copy. We also requested the Taj Group of Hotels to open up their archives; that collection had some gems.”

Denzil Smith and Rhys D’Souza at a performance of Bombay Jazz

Taking note

The team then exhibited some of these rare photographs, after which people started calling them and offered to share photos. “A Parsi gentleman called and said he had some photos, I went there, met these people and collected photographs and information,” adds Smith, mimicking the Parsi accent perfectly over the telephone lines.

Dave Brubeck (piano, seated), Paul Desmond (saxophone, standing) jamming with musicians in Mumbai (then Bombay)

“I am a hardcore Bandra ‘chokra’, who studied at the Jesuit-run, St Stanislaus High School. There were three things that defined my school days: The poverty among some of my classmates; their skills with the football; and lots of music. I think the school choir in St Peter’s Church played some extraordinary music. The process of research for Jazz helped me link history and art, political and creative freedom, among the Goans and East Indians. The play helped me re-visit those days; and it was an eye opener,” says Ramu Ramanathan, Bombay Jazz’s writer. “Mumbai (Bombay, then) was the centre of Hindi film music. The play is a tribute to the uncommon people who composed it and their dreams’” he adds.

“Set in the present, our protagonist travels through a series of timeframes and comes back from the past to tell his story: The 1940s, through the 50s, 60s and 70s, as Hindi film music evolved through the addition of Western instruments, arrangements, the influence of Jazz and those who brought it to Mumbai (Bombay, then) from Goa. The play evokes some of these characters, their lives, their musical skills — often unseen, underplayed, but inexplicably connected to the distinct identity of the film music of that era — the play captures the essence of that. The action springs from his interaction as a music teacher with his pupil,” shares director, Etienne Coutinho.

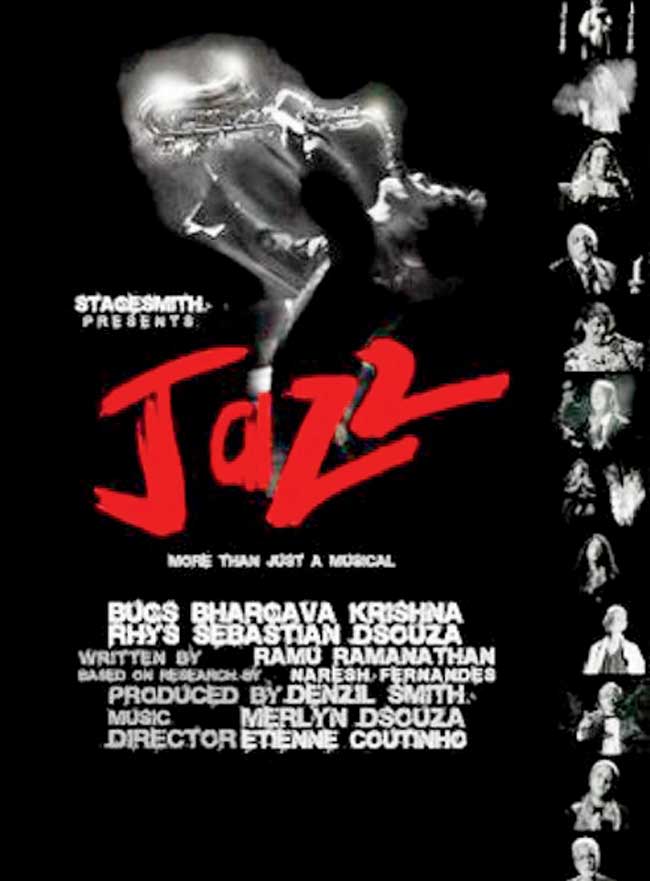

A poster of Bombay Jazz

Jazz and Hindi film music

“Bollywood music directors made use of these little-known Goan musicians to create their musical hits. They were Jazz musicians who wrote and arranged the musical parts for these orchestras and also had to play the Jazz sections and Jazz instruments. The humour is therefore scathing and dark in places. Ramu wrote the play with Denzil Smith and saxophonist Rhys D’Souza in mind, as the leads,” Coutinho reveals.

“The play is about the difficulty of people like Sebastian D’Souza, Anthony Gonsalves and Chic Chocolate, and how they found studio jobs in the larger-than-life Bollywood orchestras because of their skill with harmonies and ability to read western musical notations,” explains Ramanathan.

“People at that time, gave more than their all and sometimes, even the interludes they played were so good that they became the next compositions. These musicians were not given their due nor were they acknowledged. There is more awareness today, as people are aware of remuneration, credits and rights. People are more digitally connected to the rest of the world. For me, some of this is dramatised scenes from my childhood,” says Merlin D’Souza who has composed the music for the play.

“In 2007, I was in college when they were casting for the play and were looking for a musician. My grandfather, Sebastian D’Souza composed for Shankar Jaikishan and OP Nayyar, and I think that’s why they cast me. My character is that of a student who is talented but young and innocent. He goes to Denzil, who is a yesteryear composer, to learn. His character in the play is nameless because he represents a host of composers of that era. It’s been six years since we brought the show back, and it’s still relevant. There were things that I didn’t fully understand in the past, but today, with my travels and my exposure to clubs in the UK and New Orleans, I’ve learnt so much more,” admits Rhys D’Souza

“I play an irritable, disillusioned musician who has seen most of his friends suffer poverty and fail, as they were not given credit. He still wants to teach and makes sure his student doesn’t make the same mistakes that he did,” Smith tells us.

Sound history

The play uses audiovisual in certain sections, the highlight of which is Rhys’ jugalbandi with himself on screen. The music of the play is not typical. “We decided to use the music of those Jazz eras as a point of departure and built the musical soundscape to drive the action of the play. Merlin’s track is most important to the interpretation of the play and it is evocative and complex,” says Coutinho. “As a background, it provides an emotional grid on which the protagonist will perform,” he adds.

Talking about the popularity of Jazz in India today, Ramanathan tells us, “Musical forms like Bebop, Rock ‘n’ Roll and Cha Cha Cha are very popular. Today, Rap is doing more for versifying than Shakespeare; Jazz is the darling of the avant-garde. It will always be pedigreed minority art. One man’s Bhimsen is another man’s Miles Davis,” summarises Ramanathan.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!