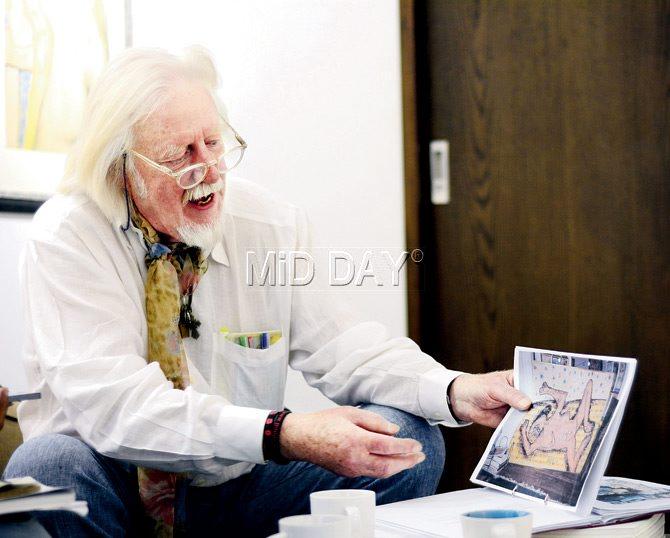

English art monger Julian Hartnoll, on a visit to Mumbai, discusses his friendship with FN Souza and dealing with the artist's nudes and crucifixions

Julian Hartnoll and FN Souza at 14 Masons Yard, London, 1995. PHOTO COURTESY SRIMATI LAL

ADVERTISEMENT

"I happen to like crucifixions very much," says Julian Hartnoll. We are not sure if Hartnoll, who describes himself as an "art monger", is being facetious or not. He offers an explanation: The scene of Christ's crucifixion and the symbol of the cross are among the most culturally and artistically reproduced tropes in the world. He picks out a bunch of trinkets veiled by a summery scarf around his neck. A filigreed Ethiopian cross jingles alongside another number embellished with flints of diamonds.

Art and life - it is as personal as it gets for Hartnoll. For the last 20 years, his Good Friday ritual has been travelling to Venice to gaze at the grand tableau of events surrounding Christ's crucifixion as envisioned by the Renaissance painter Tintoretto. "I like to look at this painting because it is so realistic," he says, slowly adding, "But Souza gets the agony of the crucifixion."

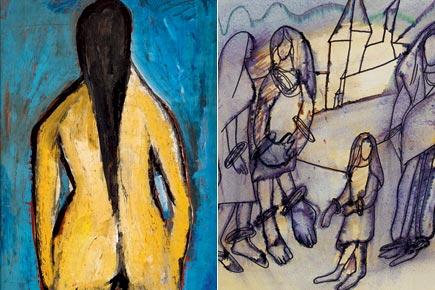

From the collection of Julian Hartnoll: Female nude by FNâÂu00c2u0080Âu00c2u0088Souza (1956)

We have been discussing a striking work by the late Indian Modernist FN Souza, in which a black Christ looks like the stretched skin of an animal. Two deformed figures keep him company. The pulsating energy in Tintoretto's is a stark contrast to the raw pain in Souza's; if Tinoretto was grand, Souza is grotesque.

Crucifixion, painted by Souza in 1959, is now permanently displayed at the Tate Britain, which acquired the oil on board piece from Hartnoll in 1993. "It is a very powerful painting showing a gruesome scene and it is not easy on the eye," he muses. As an aside, he adds, "You know Souza died on Good Friday, right?"

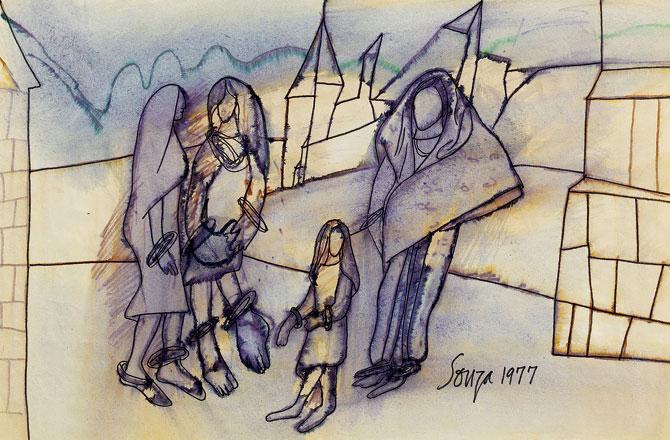

Figures in a Landscape (1977)

Did he ever ask Souza about Crucifixion? No, he says. "Our conversations weren't always art historical or academic. It's not like we spoke about art all the time. We spoke about women!" Hartnoll chuckles boyishly.

Hartnoll shies away from using the words gallerist ("a French invention") and curator ("pretentious") to describe himself. When he co-founded Hartnoll & Eyre in 1968, before setting up his own eponymous gallery in 1975, Hartnoll went in search of the artists who were "unjustly forgotten", those who were popular at one point but had fallen out of the market. Souza fitted his scope of interest. "I wasn't interested in Souza because he was Indian; he was international and unjustly forgotten," he says, alluding to the struggles that the artist faced during his lifetime.

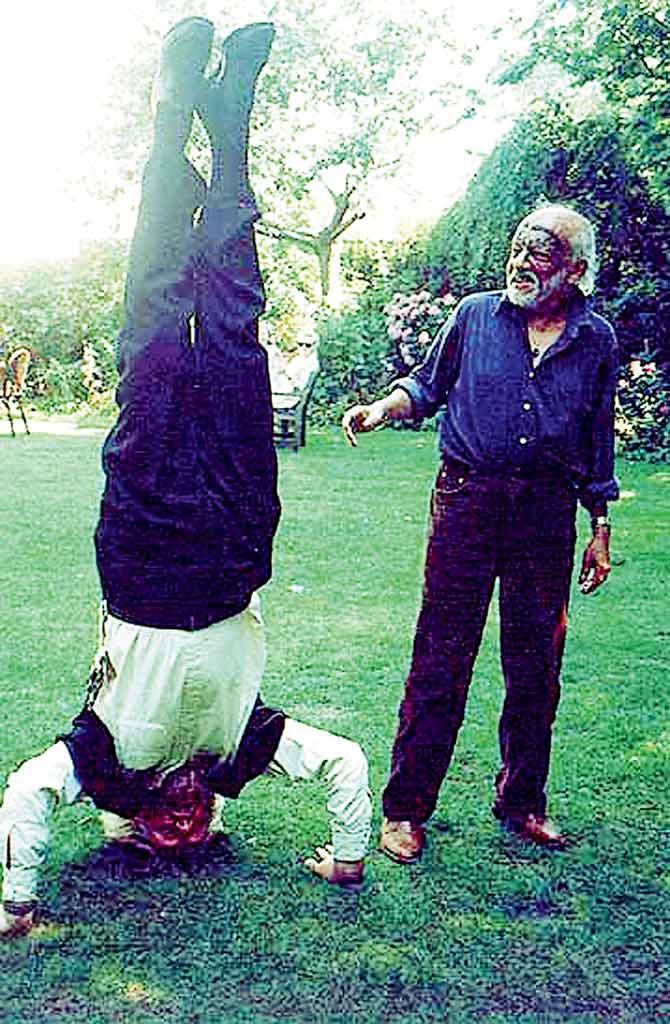

Hartnoll does a headstand as a bemused Souza looks on at The Chelsea Arts Club in August 1995. PHOTO BY SRIMATI LAL

As one who shared a deep kinship with Souza, it is a wonder that Hartnoll is able to infuse our conversation about death and outdated modes of capital punishments on a Saturday morning with the right dosage of mirth and banter. We are at Pundole's, the reputable auction house which recently shifted base to a quiet nook in Ballard Estate, on the eve of their fine art auction preview. Among the lots in the sale, set for April 12, are drawings by Souza that Hartnoll had purchased directly from the artist in 1996 and two letters that the artist wrote to him.

"I am exactly the age Souza was when I first met him," says the 73-year-old, who is in Mumbai this weekend to deliver a talk peppered with photographic vignettes of those years. 'Memories of Souza 1994-1997' coincides with the preview at Pundole's and begins with Hartnoll's search to meet Souza, the man who had made Crucifixion. After some missed opportunities, the two met at The Chelsea Arts Club, a London establishment that harks back to 1891 and boasts of members of creative and artistic repute, through the help of artist Srimati Lal.

Pic/Bipin Kokate

It started with a drink and ended with a boisterous party. Souza painted his face in an attempt of "Souza making a Souza"; a rather tipsy Hartnoll did a perfect headstand. "If you are meeting somebody for the first time, and, if, after a couple of days, you are standing on your head, that means you are getting along just fine, don't you think?" says Hartnoll. In Souza, Hartnoll found a fellow prankster and an intellectual companion. It led to a few visits to the Yatri Nivas Hotel in New Delhi, where Souza had an almost permanent lodging, and to Souza's studio in New York. Hartnoll also gave Souza his first exhibition at his gallery in 1997, with the catalogue cover featuring Souza framed through the hands of a nude figure.

The explicitness of the cover was one that Hartnoll treaded carefully with all Souza works that he bought and sold. "There are two types of Souza nudes - the female as a shape and a body which he likes for its curves, and the pornographic ones, which can be seen as rude. I went through 500 drawings at his studio to pick the ones in the auction and avoided the erotic kinds, which I don't think people can hang in their homes anyway," he says.

In Hartnoll, you find the true spirit of the art dealer. He has sold 35 paintings by Souza, but the current lot of drawings in the auction is all that he chose to own. Crucifixion, for instance, he bought for £6,000 and sold for £8,000 to Tate Britain. Today, the astronomical prices that Souza fetches in auctions do not fill him with regrets of missed opportunities. "I bought an Italian sports car for £400 and sold it for £600; I recently heard it went for £750,000. I bought a house in Belgrave Square for £600, sold it for £900. Today, it costs £9 million. This was my philosophy and it was Souza's, too."

As we wind up, we ask Hartnoll if Souza, who was known to be argumentative and difficult at times, was ever so with him. "For me he was always easy. We just got on."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!