Mumbai's old-world Indian Art Studio is one step away from making history. This Wednesday, it enters its 100th year, becoming the only photography space in the city to have sustained this legacy

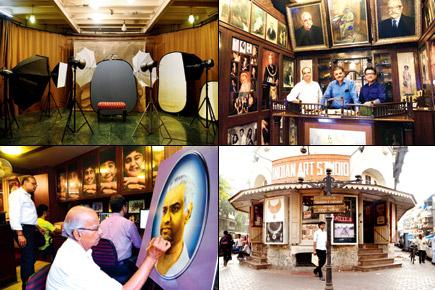

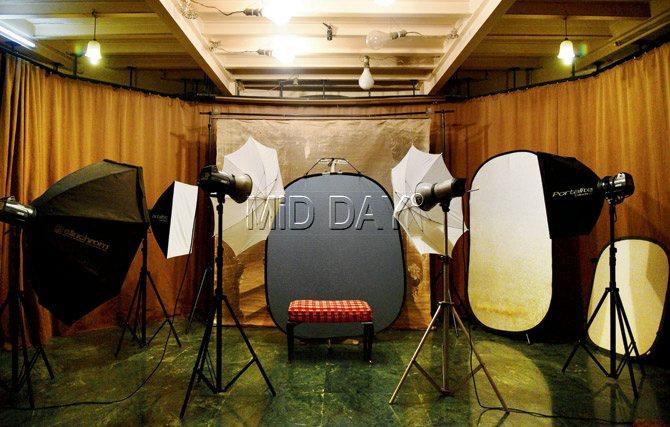

The photo studio, situated in the basement of Indian Art Studio, still boasts of original tungsten bulbs and 100-year-old hand-painted canvas backdrops, which were used for the shoots. Pics/Suresh Karkera

ADVERTISEMENT

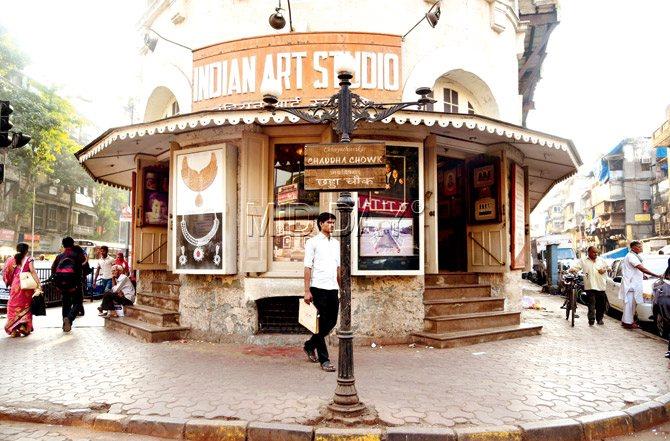

Just 10 minutes of walking through the maddening swarm of hurrying feet in Mumbai's crowded Princess Street near Kalbadevi has us craving for some quiet. When we finally take the stone steps that lead up to the triangular studio space, located in the heart of this bustling market junction, we feel like we've been heard. Here, there is a semblance of peace unruffled by the sea of chaos outside. But, it's not the studio's comforting silence, as much as its walls, which have us absorbed. Pinned on the soft boards are histories of people, who have been captured and framed by four generations of the Chaddha family.

On Wednesday, December 7, when the Indian Art Studio enters its 100th year, edging closer to its centenary celebrations, this legacy will get another lift. From being a tough competitor to nearly 15 other photo studios that once nestled in the same South Mumbai locality, to being the lone survivor of a culture eroded by digitisation, this studio has witnessed several transitions and overcome almost all.

Hargopal Singh, Jairoop Narain and Yaggopal Singh Chaddha

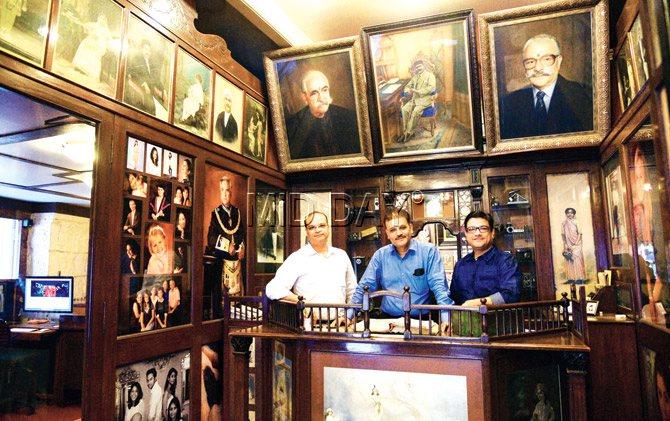

Call it the ingenuity of the three Chaddha brothers, Anil (52), Sanjay (50) and Rajesh (48), who have systematically expanded the studio's contribution to the photography space in the last 30-odd years. Or, call it the masterstroke of their great grandfather Jairoop Narain, a painter who first quit his job as a stationmaster at Bathinda station in Punjab, to buy this massive 3,000 sqft property at Gold Mohar building in 1917. Either way, there's an entire family that's hand-held this story from behind the lens.

'Married to the camera'

"There used to be a time when photography was a luxury that only a few could afford," says Anil, from across the antique teak wooden desk at his plush, but tiny office at the studio. Yet, he remembers people queuing up outside the Indian Art Studio in the 1950 and 60s for hours, just to get their photographs clicked or portraits painted. This demand would hit its peak during the festive season. With their grandfather Hargopal Singh helming the trade, the business veered into another direction. "He merged the artistic sensibility of his father (Jairoop Narain) with his own scientific curiosity for cameras," recalls Sanjay, adding that it was their grandfather, who set the stage for the brand that the art studio was to become.

Brothers Rajesh, Anil and Sanjay, the fourth generation of the Chaddha family, have slowly and systematically expanded the studio's body of work in the last 30-odd years. Also seen in the picture are portraits of

Their father, Yaggopal Singh, joined the business after completing Class 12. His three children, all students of the Sir JJ School of Arts, who now manage the studio, started working here in the mid-80s, but not before honing their skills as photojournalists. "Both, my grandfather and father believed in putting us through the grind," says Rajesh. The trio has honed its craft on a variety of cameras, including the boxy plate camera, the twin lens reflex as well as the latest, DSLR. The shelf of the reception area still flaunts a few of these photographic mantels. And, if your curious streak takes you there, the brothers are always happy to feed you in with trivia.

'Not surviving, thriving'

During the three hours that we spent with the Chaddha brothers in their quaint studio space, customers arrive, but intermittently. A woman opens the glass door of their office, and after apologising for interrupting our conversation, inquires if she could get a photo collage done — "like the one I can see displayed in the window outside". "Of course," says Rajesh, and leads her to the studio room that's on the opposite end, to introduce her to his staff.

The junction near Indian Art Studio in Kalbadevi, was renamed Chhaychitrakar Chaddha Chowk in 2009, honouring the contribution of the four generations of the Chaddha family to photography

The lack of customers would make you believe that business is alive only because of the patronage it receives due to its great legacy. But, that's far from true, Anil clarifies. "Most of our customers come here with appointments," he says.

Despite being the only surviving art studio of its kind in the area, Sanjay takes objection to studio photography being described as a "dying art". They are not just surviving, but thriving, he says. The Indian Art Studio has a battery of 35 full-time and part-time employees. At least, six can be seen working at the studio at any given time.

The studio's website boasts of a wide body of work, including commercial and industrial photography, family portraits, advertising, wedding videography and matrimonial shoots, restoration and reproduction of old photographs, oil and canvas painting and passport photography. Their clientele varies from top-notch industrialists, to the ordinary chai wallah, who just desires a quality click under the glare of the many tungsten bulbs in their old-world studio, which is located in the basement.

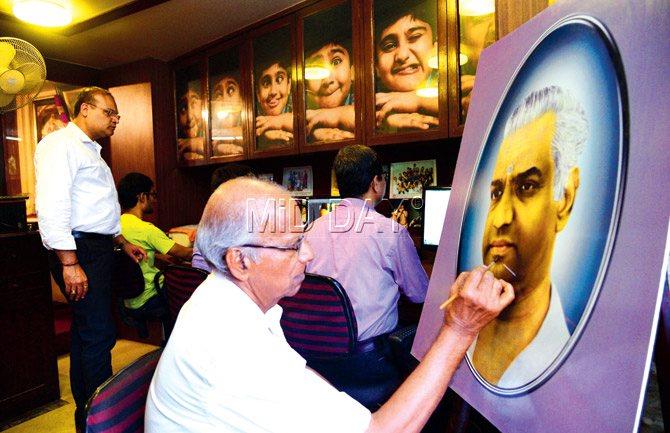

However, what this place is most known for is its hand tinting work, an otherwise forgotten art today, thanks to photoshop. Hand tinting, Anil explains, involves colouring black and white photographs with transparent paints. When colour photography was hard to come by, hand tinting blurred the lines between the real image and the colourless capture. "You can count the number of hand tinting artists in the city on your fingers. Of these, a majority have retired," says Sanjay. But, not Shashikant Mayekar, who at 72 has worked with three generations of the Chaddhas and isn't leaving this place anytime soon. "He is not our staff, he is family," says Sanjay.

Mayekar first started working with the studio 45 years ago. "I was sent to this studio by their grandfather's [Hargopal Singh] friend. I still remember delaying on my first assignment, and submitting the photo two days later than I had promised to Chaddha saab. I apologised for the delay. He heard me out and said, there's no room for sorry in our line," he recalls, in between sharpening the lines on a portrait with a sable brush. "I realised then, that the people here really believed in what they did." Though Mayekar contemplated retiring and settling with his son in the US, he says his admiration for how the three brothers have kept the business going, stopped him.

A legacy preserved

In 2009, the state government bestowed a well-deserved honour on the family. The junction at the mouth of Kalbadevi and Princess Street was renamed the Chhaychitrakar Chaddha Chowk. A wooden plaque that sits on an old Victorian street light, right in front of the grand Indian Art Studio board are among the few things that refuse to change with time.

In 1988, Anil remembers when Neil Montenus, personal photographer to former US President Ronald Regan, visited the studio on behalf of Kodak to convince Yaggopal Singh to lease his space to the technology company. Montenus not only failed, but went back a different person. Now, the brothers show us an old diary, where Neil wrote, "I hope it [this studio] will never change."

Six years later, in April 1994, artist MF Husain dropped by here, says Anil. "He told my father that as a kid, who lived in Pydhonie, he always thought twice before walking into the studio wondering if he would ever be taken seriously. He said, 'today because I am Husain, the artist, I have dared to walk in'." Such is the legacy.

Next year, when the family celebrates its 100th anniversary, a large seminal collection that traces the story of its long, unchanging tradition, will hopefully be on display for visitors. The archival work has already begun, says Rajesh, but the plan is still in its nascent stage. For people like Mayekar, who have seen the studio willfully hold on against the shifting tide, this momentous chapter will call for another photographic memory — one that he'd like to give his final touches to with his paint brush.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!