They are the Rana Raaginis fronting belligerent protests, the sisterhood that offers a comforting shoulder. A new book by a US-based academic explores the lives and politics of Shiv Sena's warrior women

A victory celebration by Shiv Sena workers at Anand Nagar in Thane in February 2012. Pic/Sameer Markande

ADVERTISEMENT

It's 7.45 on the evening of Sankashta Chaturthi, a day that calls for women in Maharashtra to keep an upvas, which is broken after seeing the moon. It makes sense then, that in the last one-and-a-half hours, Anita Mayekar and her colleagues haven't even had a sip of tea or coffee. Yet, as she trudges along Lady Jamshedji Road, in order to get home on time to make the mandated modaks, there's no sign of fatigue.

She and her colleagues are distracted by a young man, a seller of artificial jewellery. He's just got a new collection of bangles and jhumkas and the women stop to check them out. A few minutes later, they are back on their way, greeted by regular nods of acknowledgement. "Everyone knows us here and once people know you are with the Sena, you also avoid unwanted attention," Mayekar adds, a minute before turning right for her home, a few hundred metres away from their shakha on Bal Govind Das Marg in Dadar West.

Ladies of the aghadi

'M bole to main mahaan hoon Hi bole to main himmat wali hoon Aur La bole to main laakhon main ek hoon' If it were possible to summarise nearly 11 years of research in three lines, then this quote perhaps comes closest to capturing Chicago-based academic Tarini Bedi's work surrounding the Mahila Aghadi, Shiv Sena's women's wing.

Mahila Aghadi members at the Govind Das Marg Shakha in Dadar. Manisha Kayande (seated at the right-end corner), the party spokesperson, says the strength of the Aghadi is around 50,000. Pics/Sneha Kharabe

Bedi, now 44 years old, was born in Chennai and moved about the country along with the transfers of her father, a government employee. In Mumbai, Bedi, who studied at Fort's JB Petit School and later Cathedral and John Connon School and finally St Xavier's College, lived largely in Colaba. Yet, she says, "I never met a Sainik during that time, even though I knew about the party and its politics."

This is perhaps why, when she decided to pursue a doctoral research, the assistant professor at the Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois, who wanted to study the engagement of gender and politics, returned to Mumbai to study the women of the Shiv Sena. Women Sainiks, she believes, occupy a unique position as it is one of the few political outfits in the country where women have been mobilised as party workers since inception.

Jogeshwari candidate Shivani Shailesh Parab campaigning through haldi-kumkum in February 2010. Pic/Rane Ashish

Bedi, whose research has now been published by Aleph as The Dashing Ladies of Shiv Sena: Political Matronage in Urbanizing India, says over the phone, "Unlike the women's wing of other parties, where there's a clear distinction between men and women, the Shiv Sena's practices are quite progressive." She attributes this to the inclusion of people from the lower, middle and agricultural classes where the patriarchal normative standards applying to women are less stringent.

"Sena shakha boards give equal prominence to the shakha pramukh (male head) and the shakha sangathaka (head of the Mahila Aghadi)," says Manisha Kayande, 53, who juggles her responsibility as a Sena officer, with the responsibilities she has held for the last 22 years as an assistant professor at Parel's MD College.

Keeping the dashing going

'Everyone knows that I know how to kill you, how to blind you with chili powder; I can face anything. But, I am loving. If you inquire here, everyone will first say that Munde is very loving, but she is dangerous. That is what I want them to think because that is what gets my political work done. Everyone knows that I am daring and dashing that way,' Bedi quotes the motorcycle riding Bala Munde, party leader in the district outside Pune.

Dr Neelam Gorhe, a member of Pune's Legislative Council for three consecutive terms, recalls that in 2012 she started getting lewd calls at night after her mobile number was written on the walls of Pune airport

Gender equality in the Sena extends to even the militant nature of the party. Not for a second demure — or the stereotype of the 'ideal Indian woman' — the group of over 30 women here, with an age group ranging from mid-30s to mid-50s, becomes even more raucous when we bring up the word dashing. In true Sainik style, even as they insist on speaking in Marathi, they offer a synonym in their language — Rana Raagini i.e. women from the battlefield. Women who will neither tolerate injustice nor an insult to the Sena flag. They don't shy away from admitting to legal trangressions either. The cases against them, they wear like medals. Kayande says, "Every Sena leader, whether big or small, has at least 10 cases against them. There is no fear."

Rohita Thakur, a 48-year-old shakha sangathaka, draped in a lime green sari with a printed border, stands up. Three years ago, she says, she was protesting outside Sena Bhavan against NCP leader Ajit Pawar, the then-deputy chief minister, for his 'If there is no water in the dam, how can we release it? Should we urinate into it?' remark. "I was burning his effigy. The police were there and I got picked up. But, I wasn't afraid. We have got used to it now," she adds.

Dr. Shubha Raul who works with the health wing of the Shivsena party arrives at meeting at Borivali

The violence, the women insist, comes with context. Vandana Todankar (38) who has been with the Mahila Aghadi for 12 years, talks of incidents of domestic abuse. "If we catch a man beating up his wife, we give him one or two jhaapads," she adds. Another chips in, "What's the point of watching the woman die? We may as well take action now." This sisterhood of sorts extends to providing emotional support as well.

While speaking of a former corporator, Bedi writes of how Srilata Kane once spent "every day for three weeks" with a junior party worker, Malini, who had lost her husband to a heart attack. "Shock made it difficult for Malini to eat, drink, or stand up without stumbling. As Malini had no close family in Mumbai, it was Kane who slept next to her during the long nights of mourning, fed her gently from a plate of rice and lentils, raised a steel glass of water to her lips, and sang bhajans to comfort her."

Mahila Shakha Sangathak Deepali Sane speaking at the meeting on Wednesday

Shield against violence

It's been more than two decades since Dr Neelam Gorhe, a member of Pune's Legislative Council for three consecutive terms, joined the Shiv Sena. A doctor, with a degree from Worli's RA Podar Ayurvedic Medical College, Gorhe can recall the difficulties of a political life — lack of toilets in rural areas, not having comfortable pandals and stones being thrown by the masses. These, she says, are challenges that can be overcome.

What she recalls especially is an incident in 2012. "Some mischievous people wrote my mobile number on the toilet walls at Pune airport and I would receive lewd calls late at night. When I found out about the origin, workers from my party had the walls repainted," she adds. This prompt action is perhaps what women find most protective about an alignment with the Sena, says Bedi. "Often the women in the Sena are heads of households and this becomes a protective shield against domestic or other kinds of abuse," she adds.

Vandana Todanka

The turmeric connect

Much of Bedi's work, she says, was done in the background. "I introduced myself over the months at shakhas. I didn't ask too many questions. They never asked me about my politics" she adds. Soon, she says, she started getting invites to social events that often serve as networking platforms.

One such key event, she says, is the haldi-kumkum ritual. Beginning on Makar Sankranti, which falls in mid-January and extending to February, women in Maharashtra head to each other's homes where their foreheads are marked with turmeric powder (haldi) and turmeric powder in slaked lime which makes it turn red (kumkum).

Tarini Bedi

"This is where the women talk to each other and share stories. The gatta pramukhs often head to slums where all the local women come and put haldi-kumkum on their foreheads, even the unmarried women, and take the til gud offerings. The pramukhs hop through several such events in one evening. Those with the maximum amount of haldi-kumkum show it as a proof of their power," she adds.

The Thackeray aura

Most women we met had found their inspiration in the party supremo, as he is often referred to, Bal Thackeray. "The balkadu that the cadre receives is important," says Kayande, using the metaphor of a bitter medicine given to infants to ensure good health. "Here, it's the instruction received from Balasaheb and now Uddhav. What they say is an order.

Rohita Thaku

You are a Shiv Sainik, you have to obey and be punctual. If the meeting starts at 5 pm, they are here on time. For instance, there was a local election and a corporator didn't reach on time. He was pulled off the post in a second as because of his vote, the candidate lost the chairman's election. The party's order

is sacrosanct."

Bedi says she attended several events where either Bal Thackeray, his son Uddhav or nephew Raj (who later formed the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena), were speaking. While she never interacted with them, she wanted to understand the magnetism of their personalities through the eyes of the women who looked up to them.

A variety of backgrounds

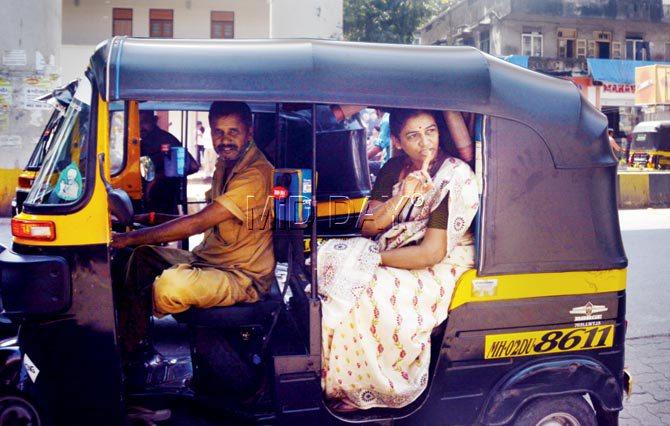

Sitting in a rickshaw she has just hailed after stepping out of her Borivli West apartment building where she lives on the 12th floor, 50-year-old Dr Shubha Raul admits that many factors were in play when she got elected, first as corporator and then as mayor. Raul, whose father, a sportsperson, was employed with the Indian Railways, grew up in Dabhoi near Baroda in Gujarat, an area that was so cosmopolitan she says, she early on got exposure to different communities and cultures.

Raul, too, interestingly is an ayurvedic doctor and was practicising until she got elected as Mumbai Mayor in 2007. She says she would often conduct health camps in her area, work that brought her in close contact with local Sena and BJP workers. It was in 2002, she says, that Sena workers asked her to join the party, an offer that she says she initially rejected.

"I didn't know what a corporator was or what they did. I would vote depending on what my family said. But, they kept pursuing the matter," she adds. Once, she even ran away to Matheran to escape the persistent Sainiks.

A word from her mentor and a call from Uddhav, asking her to be ready as the party wanted an "educated woman to contest from the seat". Luck it seems was rooting for her. "First, the constituency became reserved for women. Then it became reserved for OBC; all this helped," she admits.

How has her political career changed her personally, we ask. "I have become more aggressive," she says. As Mayor, she barged into the city's hookah parlours, clamouring for them to be shut down. That there was no law at the time against their functioning didn't matter. There had, she says, been complaints of them becoming addas for drug abuse. "We told the owners that we would bring in the laws, but they'd have to shut down first," she adds. She has become angrier as well, she says. "But, without aggression often it's difficult to get work done."

Leaving a legacy

It's the idea and opportunity to get something done, to leave a political legacy — "even if it's just getting a toilet built in their area" — Bedi says, that encourages the women to continue with their work. It's this political effectiveness that informs their daily lives.

Bedi quotes Ragini Munde of Mumbai and writes, "When some work needs to be done, Shiv Sena women never think 'what if something happens to me?' Instead the thought is 'whatever is going on there, why don't I go and resolve it'. So, I have been doing this resolving for some time now. In this area wherever I go, everyone runs behind me. They all know me now. Whenever anything goes wrong, I am the first one to run there and do some 'dashing'."

With inputs from Chaitraly Deshmukh

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!