In the era before the touchscreen, it was the humble typewriter that symbolised India-s economy and propelled women into the workforce. But, the last key has not been punched yet, finds a new book

Final Mechanic, Danny Jalnawala at Godrej Typewriter Plant, pours over a Prima typewriter, listening intently to the sounds it makes while he tests the keys. His colleague, Gopal Shetty, stands a few paces behind him, watching him and making fun of him fo

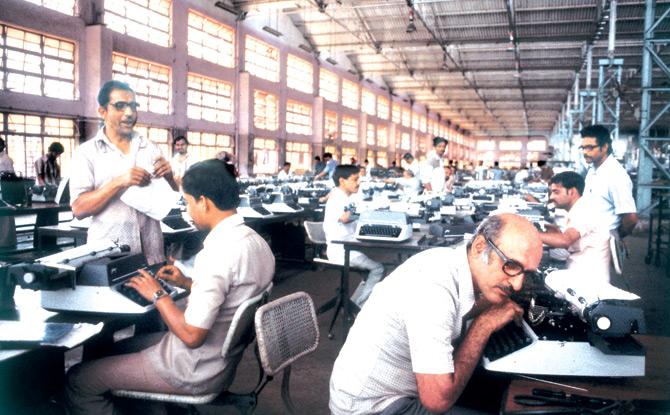

Final Mechanic, Danny Jalnawala at Godrej Typewriter Plant, pours over a Prima typewriter, listening intently to the sounds it makes while he tests the keys. His colleague, Gopal Shetty, stands a few paces behind him, watching him and making fun of him for working so hard. Also seen in the picture are: Subhash Raut, a test-typist left, foreground; sitting, Querobino Fernandes, Lopez, Kalim Haider, Baig, Lad and Vinayak Karnik. Pic/Sooni Taraporevala, 1984

ADVERTISEMENT

It was the year 1976, when Sidharth Bhatia walked into the Free Press Journal office on Dalal Street and was led to a table that had around eight typewriters sitting on it.

Those had to be shared among 15-20 journalists, recalls Bhatia who went on to work in several publications over the decades that followed. "I have seen the transition from typewriters to computers," he says. That-s perhaps why he was commissioned by Godrej, the last firm in the world to manufacture manual typewriters, to put together a book that traces the journey of the typewriter in India, hauntingly titled With Great Truth & Regard.

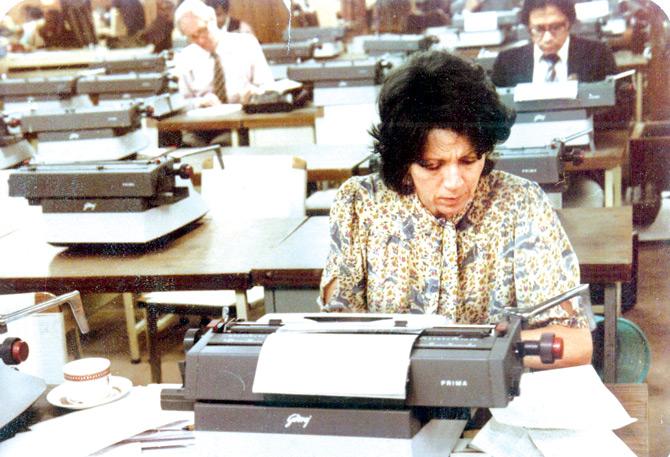

Journalist in the media room at the Seventh Non-Aligned Movement Summit, Delhi 1983. Pic/Godrej Archives

"When Godrej rolled out their last typewriter in 2011, they were quite surprised with the media attention they got from around the world. I think that-s when it must have struck them that the story of the typewriter in India is worth revisiting," says Bhatia explaining the genesis of the book.

Right at the onset, Pheroza Godrej, wife of Godrej & Boyce chairman-MD, Jamshyd Godrej, made it clear to him that the book was not going to be about the Godrej typewriter, but about the culture of self-reliance that its analog keys hammered mid 19th century onwards.

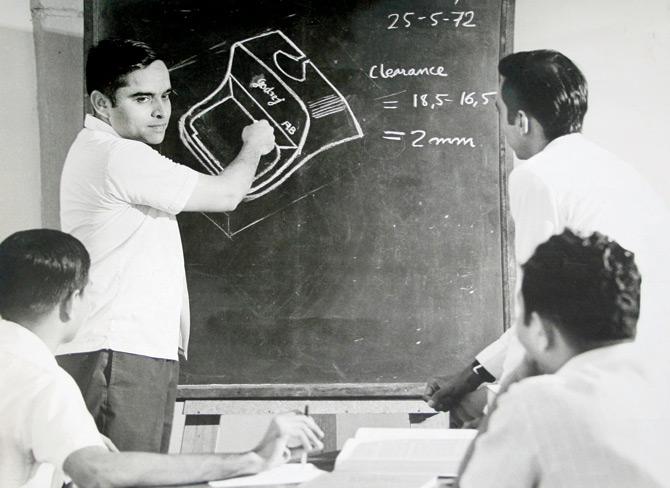

The design team at Godrej during a training session, circa 1972. Pic/Godrej Archives

"This was long before Make In India, there was no foreign exchange, only lots of determination to self-produce," says Bhatia, who is presently the editor of The Wire, an online publication.

His research took him to several corners of the country, to compile inputs from some of the best known wordsmiths and the street-side stories that he learnt during his travels to Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Surat and Dehradun, to name a few.

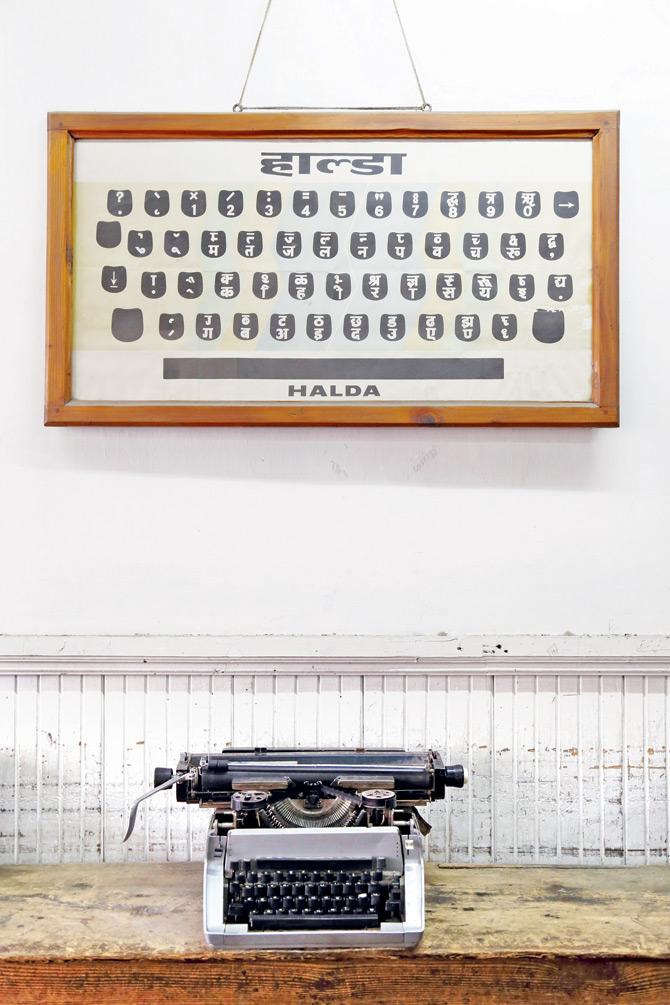

A Halda Devanagari keyboard poster on the walls of the Modern Era Stenographic Institute, Srinagar. Pic/Chirodeep Chaudhuri

"I met Ruskin Bond in Landour who showed his present typewriter — it-s his third, I think. He bought his first in England, in his early 20s. The other two he purchased in India," Bhatia says. The book also has a piece by noted columnist Santosh Desai on typewriters in government offices and one on typewriters in Kolkata by Jug Suraiya. It-s, however, the street-side stories that Bhatia remains fascinated by.

"I met a man in Delhi who sells second-hand typewriters and has been in the business for decades. That his customers include teenagers wanting to try their hands at the machine, was an intriguing find. Even in Chor Bazar, I heard similar stories and their buyers also include hotels and restaurants wanting to add a retro touch to their décor," Bhatia recalls.

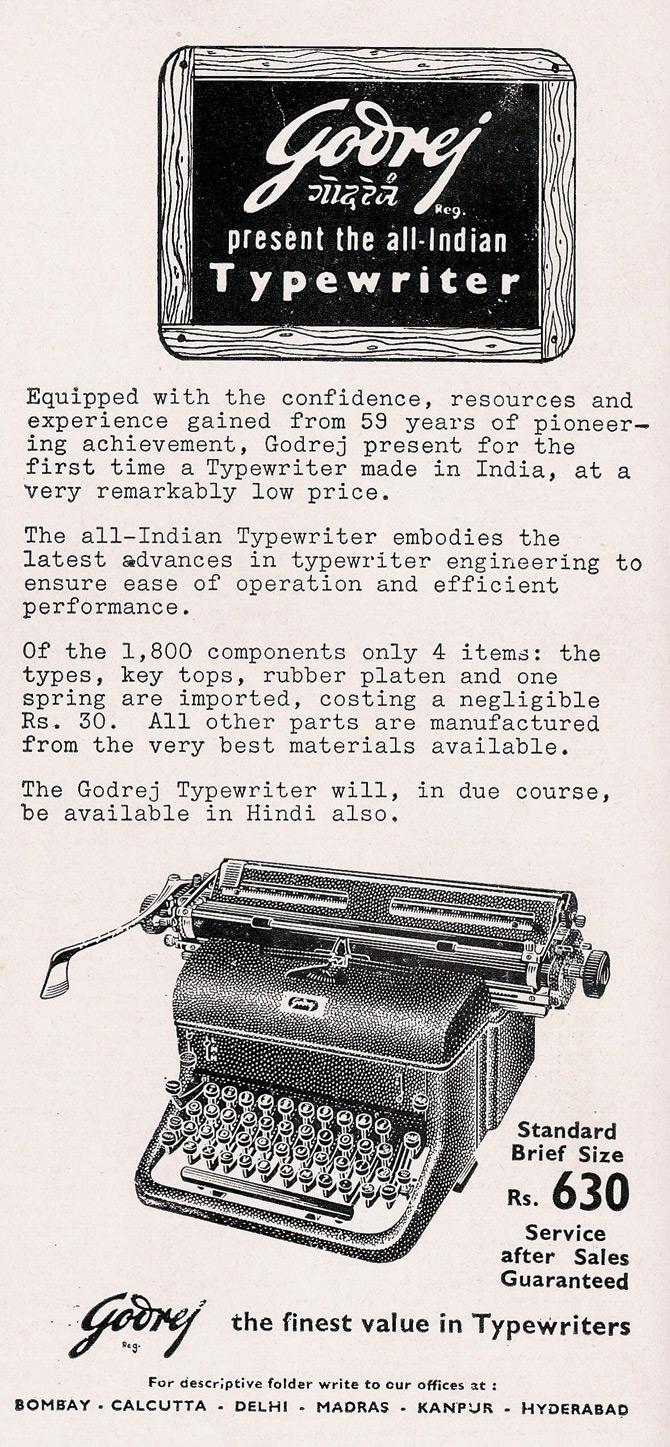

An ad from 1956. Pic/Godrej Archives

Over the four-and-a-half years that went behind putting the book together, Bhatia discovered the myriad ways in which people continue to cling on to this past remnant.

"Typewriting schools are still functional in some parts of the country. They are there in Kolkata where young girls learn to type, so they can use the same skills on a computer. As they don-t have the resources to invest in a computer, this is their second best option," he says.

Sidharth Bhatia

But then, how does the analog training come in handy on an electronic device? "The Qwerty keyboard was invented with the typewriter — the arrangement of keys was scientifically done. People are so used to Qwerty that the format has stuck. There-s a school in Girgaon that holds typewriting exams under the state board," he says.

The book also traces how this machine became a tool of employment in the 50s and 60s, when women began to look beyond a career of a "nurse" or a "teacher".

"It marked the rise of the secretary, thanks to the influx of corporate houses in need of personnel with a working knowledge of English. Parents didn-t object to their daughters opting to become secretaries and typists. After all, that-d ensure their shift ended at 5 pm. Those times found expression in films too. If you look at Hindi films of the 50s and 60s, you-ll see the typist is always a woman."

The book is also a repository of telling captures by photographer Chirodeep Chaudhuri who often accompanied Bhatia on his travels. "He has a quirky eye, some trips he took on his own too and we-d constantly exchange notes. Besides, the Godrej archives are a goldmine and some of the most prized historic shots in the book have come from there."

Of all his stumbles, there-s one that tops Bhatia-s list. "In Allahabad, I met a man, who is the only remaining manufacturer of typefaces in the world.

The typewriter has 2,000 parts and he makes the font that strikes the paper. I visited his workshop to see the artistry behind it. The cut of the stencil, the right amount of dent that it makes on the paper so it doesn-t tear, — it was a fascinating watch. And, who would have thought that the last one surviving would be in the bylanes of Allahabad?"

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!