Why have some of us made it our daily mission to customise news feeds for social media users?

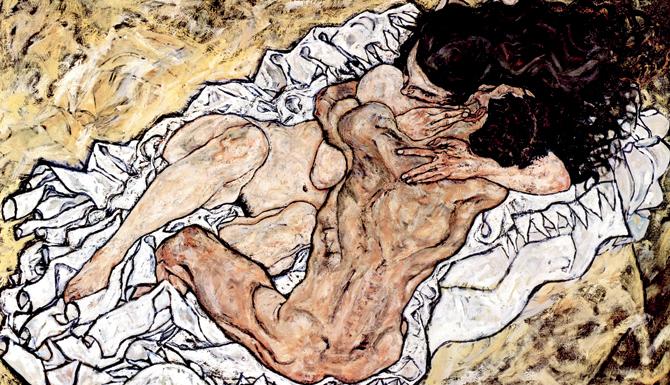

Embrace

When the Modi government issued an order last week through the Department of Telecommunications, directing Internet Service Providers across India to block 857 porn sites, Nitesh Mohanty opened his Facebook account (nitesh.idesign) to pay tribute to the ultimate ‘pornographer’ of the 20th century. He posted a picture of The Embrace, a 1917 painting of lovers, naked, in a tender grip. Its maker, Austrian artist Egon Schiele, was jailed for 24 days for exhibiting erotic drawings at his studio, after the judge decided to burn one of his offensive drawings over a candle flame.

ADVERTISEMENT

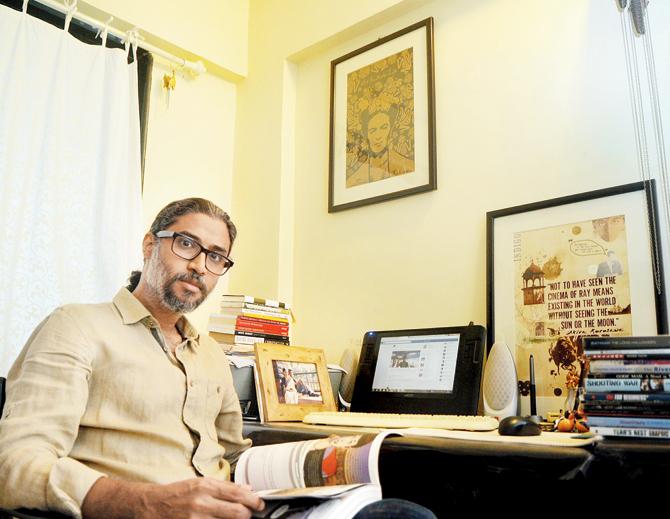

The picture was one of 10 that Mohanty, visiting faculty for visual design at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, posts every day for his 4365 Facebook followers, who wait for his handpicked mix of posts on art, culture, cinema and photography each morning.

Nitesh Mohanty (above) curates posts on art and culture on his Facebook account. He posted a picture of The Embrace (Top) by artist Egon Schiele the day the Indian government imposed the porn ban. PIC/Nimesh Dave

The 40-year-old compares the social media tool to the softboard inside his hostel room at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, back in the year 1997. A postcard, a scribble, the picture of a beautiful muse or a cutting from a magazine — it would all make its way there. Five years ago, when the Borivli resident encountered Facebook, he saw it as a limitless virtual mood-board. “My motive is quite selfish,” he says. “Before I lose out on a poet or photographer, I make a note on my page, like I would in a journal. As I plunge into discovering strange and obscure artists, my posts seem to have resonated with an online audience.”

Discussing the performance art of Marina Abramovic or the painted photographs of Saul Leiter, Mohanty is one of a new breed of online curators who spend endless hours filtering the worthwhile from digital noise to share with loyal subscribers or followers. Mohanty says his posts, numerous but erratic, tend to be driven over a day, week or month by a theme. He knows his reading and research has paid off when comments pour in, sparking off a discussion. “There are those of us who walk into a gallery and don’t understand what’s up on its walls. Here, it’s about having a conversation on why he painted and what he painted.” Followers can pose questions, indulge in debate, or simply Like, without comment.

Pooja Saxena

Curated online accounts like Mohanty’s follow the league of global curating platforms like Brainpickings.org, a “one-woman labour of love,” by Bulgarian writer and “hunter-gatherer” Maria Popova. She started by sending a weekly mail with delectable slices of art and culture, “a record of my own becoming as a person – intellectually, creatively, spiritually — and an inquiry into how to live and what it means to lead a good life.” Brainpickings now has 3.6 million subscribers on Facebook. The site remains ad-free, relying on donations.

Anisha Sharma

Mumbai-based social media observer, Manveer Singh, says curators are “driven by passion and bring content that is not easily available to the online viewer.” Most accounts are extensions of their personality. But, like most offline curators, this breed too has discerning taste and a niche specialty.

Anu Rana curated Mai Ly Degnan’s illustration for mangopopsicle.org

Bengaluru-based Pooja Saxena, for instance, started a Flickr account (anexasajoop) in 2013 called Newspaper Nameplates. Here, she uploads newspaper mastheads, from the standard to the obscure. She posts in bulk every month, sourcing newspapers while travelling or asking friends to contribute. The 122 mastheads in her virtual gallery reflect her offline collection which serves as an archive for those researching fonts and typography. “People are interested in visual culture. They like collecting matchboxes and film posters. These are objects with a strong language,” says the 27-year-old independent digital design consultant.

Consumers have a host of options to explore before they decide what will trickle into their news feeds. It could be delectable food photographs on @mumbaifoodie or a curated mailer on art, literature and poetry from Kolkata-based Rohini Agarwal’s, The Alipore Post. The trend of curation, says 34-year-old Mihir Bijur, isn’t a new one. Bijur, who invented the hashtag #embee (inspired by his initials) in 2009, is associated with music content on Twitter. Bijur recalls “#np #embee” nights, when he used to tweet a throwback playlist and would be joined by 10,000 more tweets. “We were mass-curating at a time when hashtags weren’t that popular and when there wasn’t so much outrage on Twitter either,” says the food entrepreneur, who listens rigorously to retro artists.

Back then, it was organic reach. Now, with brands putting up paid advertisements on Facebook and promotional tweets everyday, Singh believes that Instagram is the last refuge of indie curators.

Anisha Sharma would agree. The 27-year-old, who manages her account @ghaatidancer on Instagram, scours through surrealist works before concluding with a post of an artwork between 11 and 11 30 am, with no hashtags. Shying away from mainstream promotions, she says, “Curation is subjective. I don’t want it to be about followers or numbers. I want to keep it about art.”

This also means a distaste for Facebook pages that post artworks with an “inspiring” or “sentimental” quote. Quotes and art should be kept separate, says the writer and Dali aficionada. Jovanny Varela-Ferreyra, curator of Berlin-Artparasites, a Facebook page sharing artworks and quotes from different artists is used to receiving 15 lakh Likes for a post. When asked where he forages for matter, he said, “You are asking the drug dealer for the source, the magician for the trick behind the illusion, and the chef for the recipe.”

Anu Rana, US-based art director of Indian origin, manages mangopopsicle.org, a website of imaginative fringe art. While she uses the nifty Google to land the best art, over time, she has begun receiving fitting global submissions. “I decided I didn’t want to be exclusive,” she says. “Personally, I appreciate a broad range of creativity, but the site is celebratory and avoids work that is particularly sad or cannot see sadness as a blessing.”

Singh says that the beauty of online curation is precisely this. What you feed the world is fed back to you, in a digital karma of sorts. “Curators need to invest time and diligence. But over time, they will see that they can run their account on auto-pilot, with the best content seeking them out.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!