I recently heard an Odia song where Lakshmi and Parvati tease each other by mocking each other's husbands. Lakshmi wonders about the health of Shiva's mount, Nandi, who she describes as an old weak bull. Parvati retorts by describing Vishnu as a cowherd who should know more about the health of cattle

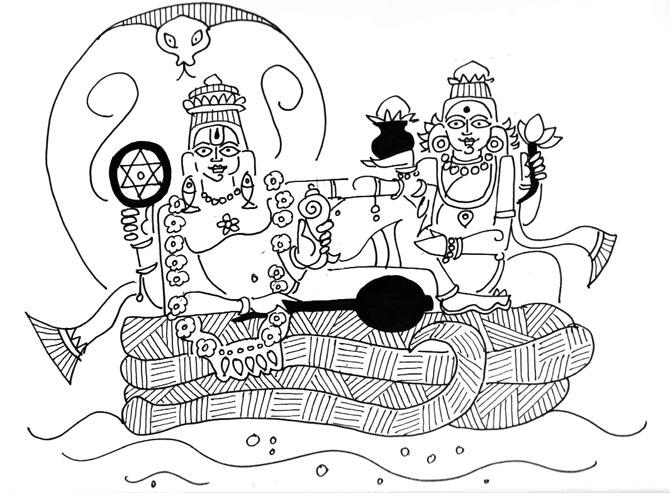

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

ADVERTISEMENT

I recently heard an Odia song where Lakshmi and Parvati tease each other by mocking each other's husbands. Lakshmi wonders about the health of Shiva's mount, Nandi, who she describes as an old weak bull. Parvati retorts by describing Vishnu as a cowherd who should know more about the health of cattle.

I recently heard an Odia song where Lakshmi and Parvati tease each other by mocking each other's husbands. Lakshmi wonders about the health of Shiva's mount, Nandi, who she describes as an old weak bull. Parvati retorts by describing Vishnu as a cowherd who should know more about the health of cattle.

To put an end to this verbal joust, Shiva and Vishnu merge into one being Hari-Hara, to show they are the same, not different, not higher or lower. The song uses a very household scene to evoke Shaiva-Vaishnava rivalry that was at its peak in Odisha 500 years ago. The problem is resolved in a very Hindu way: the two gods are seen as two aspects of the same divine. In this song, God is not perfect. God has many forms, and each form — male and female — has flaws. The female forms quarrel. The male forms are inadequate. Each form completes the other, making them all part of a jigsaw puzzle.

However, nowadays, if you make fun of a Hindu god, point to his or her imperfection, like Ram's inability to be a good husband, Shiva's inability to give up his fondness for bhang, or Krishna's failure as a father, or Saraswati's arrogance, or Lakshmi's fickleness, or Kali's violence, people get upset. They feel outraged. They feel to criticise any aspect of divine, or tolerate jokes on gods and goddesses, is a sign of heresy, and disrespect. 'How can you say such a thing about our God?' they ask angrily. Then they point to terrorists who blow up Europeans who make fun of Allah, and his Prophet. That, sadly, has become the benchmark of faith.

The idea of God as perfect came from the Greeks, specifically Platonic philosophy that spoke of the 'ideal'. This Greek idea was imposed on the Christian notion of God when Christianity became popular in the Greco-Roman world about 1,800 years ago. The early Christian God was a jealous, but just, tribal deity of Semitic tribes, who punished those who did not follow his commandments. Jesus Christ made him a loving God who forgives the disobedient and even sacrifices his son for the salvation of sinners. But it is the Greeks, who translated much of the Bible from Aramaic to Greek, who turned the jealous God of Moses into the loving God of Jesus into one who is all-powerful, all-seeing, just, benevolent and perfect.

This view informed in Islam 1,400 years ago. Since God was perfect, and his creation was perfect, Muslim clerics forbade artists from recreating images of God or his creation (plants, animals, humans) using paint or stone. These views reached India with Islam, and mingled with very different views of God, such as those found in the poetry of Tamil Alvars and Nayanars, who imagined God as Vishnu and Shiva around the same time.

Colonisation enforced Christian thought via educational institutions. God of all religions became the same: all-powerful, just, benevolent, and perfect. In other words, God was reduced to one rigid definition, a definition used in court cases on temple rituals and beliefs. This definition denies the protean Hindu God from being simultaneously powerful yet powerless, perfect yet imperfect, infinite yet finite, regal yet comical, different for different poets and communities, different in different contexts. Time to liberate the Hindu God from the Abrahamic, or should we say Greek, template?

The author writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt@devdutt.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!