Abhi abhi yahin tha kidhar gaya ji?" (hey, have you seen my heart/It was just here, now it's gone) being the most famous

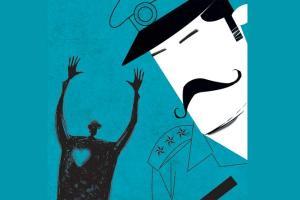

Illustration/Ravi Jadhav

In one of the sweeter stories I have read in a long time, a young man in Nagpur approached the cops, longing for some solution to, well, longing. He came in wanting to file a complaint saying his heart had been stolen. The cops were nonplussed and uncertain about the procedure for dealing with this kind of lost property. They could have laughed it off, but instead, consulted their superiors. Finally, they had to tell the young man there was no section of the Indian law — and probably no 48-hour constitutional amendment likely, unlike for dismissing CBI chiefs — under which they could deal with his problem. I wonder what the young man did.

In one of the sweeter stories I have read in a long time, a young man in Nagpur approached the cops, longing for some solution to, well, longing. He came in wanting to file a complaint saying his heart had been stolen. The cops were nonplussed and uncertain about the procedure for dealing with this kind of lost property. They could have laughed it off, but instead, consulted their superiors. Finally, they had to tell the young man there was no section of the Indian law — and probably no 48-hour constitutional amendment likely, unlike for dismissing CBI chiefs — under which they could deal with his problem. I wonder what the young man did.

ADVERTISEMENT

As there are few more helpless emotions than love, it is not surprising that we constantly seek help for it: from agony aunts to cops. The difficulty and glory of love is that it is so abstract. After all, how can your heart be stolen when it is beating just fine in your chest? It's a puzzle that is the topic of many a Hindi film song: "Jaane kahan mera jigar gaya ji? Abhi abhi yahin tha kidhar gaya ji?" (hey, have you seen my heart/It was just here, now it's gone) being the most famous.

Even the most stubbornly prosaic of us understand the poetry of this abstraction. Love and all its by-products are physical — they take place in the body and you can feel a thudding heart quite clearly; as well as metaphysical — we are not sure how to explain a connection, an awareness, a desire that swells even when it has no purpose or result. But the metaphysical and physical are both real, aren't they? We legislate for everything, but rarely for emotions. And when laws and identities are the only ways to be valid in the world, we feel shaky and lost. We are not altogether sure of ourselves, not sure other people understand and recognise our experience as valid, in the same way as they recognise loss to property or identity. People pretend their emotions are actually something else: if you are hurt by someone you may avoid them, pretending you are busy. Or, a superior whose sexual advances have been rejected by a subordinate, might pick on them, pretending it's about work, not anger.

But should we legislate for emotions? Emotions, which are like that wandering jigar, one minute here, one minute disappeared? Maybe there is no one answer to that. But for those things that we can see and yet not quite see, like love (as opposed to a publicly declared or sanctioned relationship), or mentorship, or even inspiration that we take from other people's art and ideas, there is a parallel system of fairness we call ethics. A recognisable, though not enforceable, set of behaviour of reciprocity, respect, consent and acceptance. Perhaps, there should be a way of talking about this alongside law — as the feminist writer Madhu Bhushan described in a discussion: love and order, not just law and order. Meanwhile, we may never know how things turned out for the young man, but I suppose we can all guess, that one day he will suddenly realise his stolen heart has found its way back and is sitting pretty, waiting to be stolen again. That's the law and order of love.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at www.parodevipictures.com

Catch up on all the latest Crime, National, International and Hatke news here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!